- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

When some of the world’s most powerful people want help changing it, they call Whitney Williams ’94

The woman who roams the world missing Montana scrolls through her smartphone, scanning old messages.

“She left me the sweetest voice mail the other day,” Whitney Williams says. “I think this is it.”

Williams leans in and hits the play button. And even though she knows whose voice is about to ring out, Williams still beams and shakes her head at the sound of it.

“Hey, Whitney. It’s Hillary calling.”

First lady. U.S. senator. Secretary of state. Presidential candidate. Hillary. Just calling to, you know, say hey, and, thanks. After all, the two have worked together for more than two decades.

“I get calls from her every now and again,” she says. “And it’s like, ‘What an amazing life I have.’ My God! So I said to my nephew, ‘Find a way to save that.’”

Founder and CEO of Seattle-based social impact consulting firm williamsworks, Whitney Williams has dedicated her life to doing good in the world. And if the roster of powerful, wealthy people who turn to her for advice is any indication, she’s done it well.

In the twelve years since launching her firm, Williams has helped people, foundations, and corporations give their money and use their influence in ways that have brought about real change in the

U.S. and in some of the most impoverished, conflict-riven corners of Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. She counts among her clients the Clinton Foundation, Bill and Melinda Gates, Bono, Bobby Shriver, the Nike Foundation, Google.org, and CAREthe largest relief organization in the world.

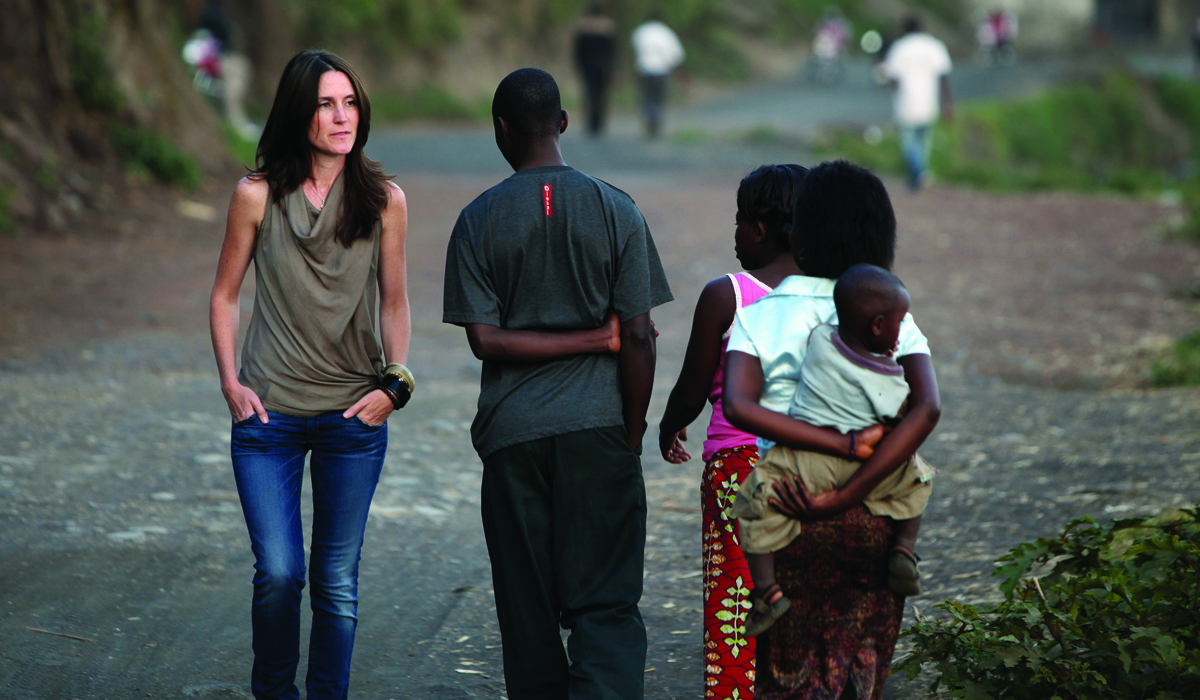

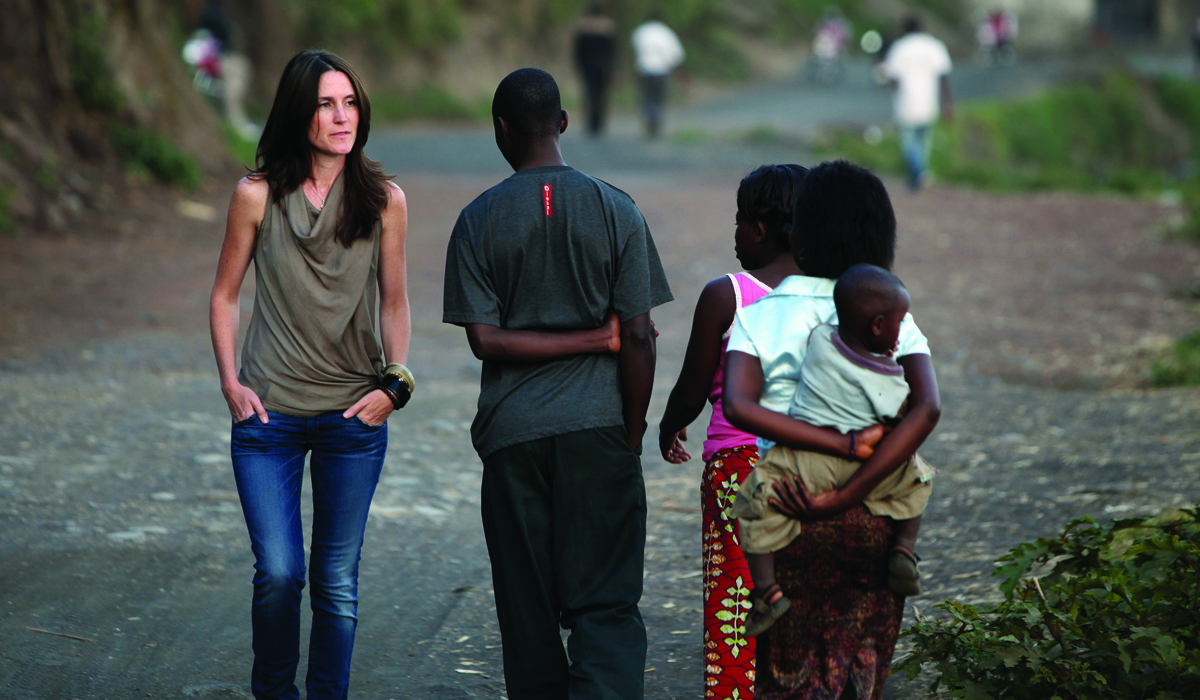

In 2009, Williams and actor Ben Affleck founded the Eastern Congo Initiative. The advocacy and grant-making nonprofit focuses on supporting efforts to rebuild civil society in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where war, disease, and poverty have killed an estimated 5 million people since 1998. The Eastern Congo Initiative has made nearly eighty grants totaling $5 million‑for thirty-five local Congolese organizations since its inception and leveraged hundreds of millions of dollars in new investments from governments, philanthropists, and the private sector.

Her passion for business, policy, and philanthropy has allowed Williams to tap into a value system and a network she began developing in childhood as the daughter of Pat Williams, the nine-term Montana congressman, and Carol Williams, the first woman minority and majority leader of the Montana Senate.

“The idealism in me,” Williams says, “definitely comes from what I think of as Montana roots.”

Williams spent the first eight years of her life in Helena, within two blocks of current Montana Governor Steve Bullock’s childhood home.

“When Pat was first running for Congress, Mrs. Williams would bribe us all with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and we’d go door to door around Helena,” Bullock says with a laugh.

Her father’s election took the family to Washington, D.C.

“I always knew I would come home to Montana for college,” Williams says, and in 1989, she followed her older brother, Griff, and sister, Erin, to Missoula, where she majored in political science and minored in Native American studies and wilderness studies.

Williams’ guiding principle—anything is possible—began showing itself in Missoula. When she learned the University didn’t offer native languages, Williams found a teacher at Blackfeet Community College willing to travel to Missoula. When UM didn’t list the course in the catalog, Williams printed fliers, stuck them up around campus, and recruited enough students to fill UM’s first Blackfeet language class.

Bob Ream, professor emeritus in UM’s College of Forestry and Conservation, met Williams when she signed up for his intensive Wilderness and Civilization Program, where twenty-five students are immersed in studying wildlands and how they intersect with people, the arts, and the economy.

Then, as now, the forty-year-old program kicked off with an eleven-day backpacking trip on the Rocky Mountain Front.

“I don’t think Whitney weighed much over 100 pounds,” Ream remembers. “I looked at her carrying this huge backpack, and I thought, ‘Whoa.’ Her pack had to weigh forty pounds. She was tough.”

Williams—who, as an adult, has traveled to more than eighty countries—calls it one of the most memorable trips of her life. Even though she was an experienced backpacker, the college junior had never spent a night in the wilderness alone, a requirement of the program. On the assigned night, an early snow fell.

Williams remembers how the snow piled up around and over her.

“It was scary,” she says. “It was one of those moments you realize, ‘I have to figure out how to take care of myself and how to ask for help.’”

Williams took a break from her studies for a four-month White House internship in President Bill Clinton’s Office of the Public Liaison, which, in its way, served to be its own immersive experience, this time into the intersection of power, influence, and access. Williams was likely the only intern that year who was asked to encourage her father to support the president’s first-ever budget.

The inclusion of a controversial gas tax made the congressman’s vote shaky, so Williams ferried home statistics about the tax, taping them to her father’s shaving cream, milk carton, and steering wheel.

Williams’ upbringing may have conveyed certain privileges, but it didn’t saddle her with a sense of entitlement.

“People have always observed that she has a ‘Golden Rolodex’, but what is wonderful is that her Rolodex is full of friends from all stages of her life, and she is great at staying in touch with them,” says her mother, Carol.

After bouncing around Montana for a bit as an aide to Missoula’s Democratic legislative delegation, then as an archivist for the Women’s Protective Union in Butte [her salary paid by a grant she wrote herself], Williams returned to Washington, D.C., and a public relations job. Eager to get back to the White House, she offered to work for free, coordinating and planning events along Hillary Clinton’s It Takes A Village book tour. After another volunteer gig as an advance person for the first lady’s overseas travel, Williams worked herself into a paid position as Clinton’s trips director at the age of twenty-seven.

“And I got a chance to see foreign policy come to life,” Williams says.

The job required logistical expertise and public-policy savvy, but Williams’ most valuable asset was her ability to get ordinary people talking about extraordinary issues—such as the Northern Ireland Peace Process—in front of the first lady, who had the megaphone that could amplify their voices.

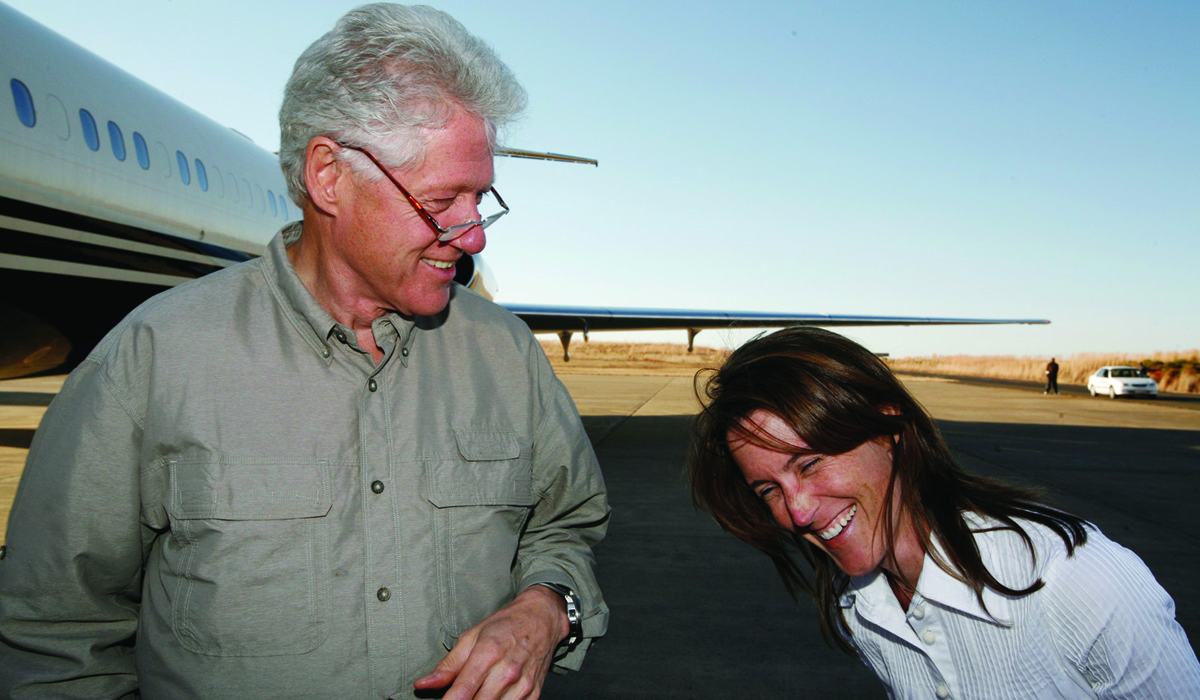

“She’s one of those rare people who is always doing the right thing in her unique way, with passion, creativity, and good humor,”

-former President Bill Clinton says of Williams.

And by 2000, the woman who found herself through immersive experiences—in the wilderness of Montana and the wilderness of politics—was ready to take that mindset into her own business.

In her consultancy, Williams susses out her clients’ passions, then puts together customized trips to expose them to dangerous regions, complicated political landscapes, and the locals who navigate these places in pursuit of change.

After her clients return home, she helps them put their money—and brand—to work for high-impact social justice.

One might be tempted to dismiss philanthropy as something wealthy people do to assuage their guilt. Maybe that’s true in some cases, but not among the people Williams advises. They want results.

When Bill Gates and his wife, Melinda—williamsworks’ second client—focused their attention on India, it was with the goal of stopping the spread of HIV. So Gates used GIS mapping of new HIV cases to uncover a pattern of truckers spreading the disease through sex workers they encountered along India’s primary highway.

“That’s the set of questions that arises from someone like Bill, who is a tech guy at his core, who thinks about scale, who thinks about technology as a way to solve some of these problems,” Williams says.

Another of Williams’ clients, Laurie Michaels, established a fund that gives one-time grants to groups in danger of losing major aid because of logistical or unexpected roadblocks—think of hundreds of thousands of dollars in donated medical equipment sitting unused on a loading dock because the Congolese hospital it was destined for—couldn’t afford the shipping costs. The Open Road Alliance was born to address these types of opportunities and challenges.

“The common denominator for our clients is a sense of responsibility,” Williams says. “People feel that they’ve been blessed, and that they’ve lived in a country that has provided a lot of resources for them to become what they have become. They have a real sense of obligation—in some cases, moral responsibility.”

Most people get referrals from college professors or the last boss they didn’t tick off. Williams got one from Bono, who pointed Ben Affleck her way when he was trying to figure out how he could make a difference in the world.

They spent two years exploring Congo, and in 2009, Williams and Affleck started the nonprofit Eastern Congo Initiative with seed money from Howard G. Buffett, who she and Affleck call ECI’s godfather. Philanthropists Laurene Powell Jobs—widow of Steve Jobs—and Pam Omidyar—whose husband, Pierre, founded eBay—also were early investors, as was Google.org.

Williams contributes to the initiative financially every year, and says her company has given more than $5 million in pro bono work to ECI since it began. Affleck and Williams also have sought to raise the region’s profile by prodding the U.S. Congress to invest more aid in Congo to strengthen it and lay the foundation for long-term peace and stability.

Believing diplomacy is critical, they encouraged the State Department to appoint a special envoy to the region, which required convincing a handful of key policymakers, Williams says.

“We call that power mapping,” she says. “Here’s the problem we’re trying to solve. Let’s get really strategic about who to influence so we don’t spend a bunch of time, money, and effort educating people who are not decision makers.”

Lately, Williams and her team have been noodling about how the release of the new Batman movie—starring Affleck—can leverage new investors for ECI.

Their efforts have resulted in deeper engagement by the U.S. and foreign governments; increased funding for maternal, newborn, and child health programs; and multiple visits to Congo by members of Congress, as well as Secretary Clinton and Dr. Rajiv Shah, former United States Agency for International Development administrator.

“Whitney’s hard work and legendary determination are leaving the world better than she found it. Hillary and I are proud of her, grateful for our long friendship, and thankful for her support of the Clinton Foundation’s work around the world,”

-Bill Clinton says

That work is endless—and rewarding. ECI funds rape prosecutions in Congo, infamous for having one of the world’s highest rates of rape. Williams recalls a July meeting where eighteen of the twenty Congolese present had been raped, including two girls under age five. They took turns sharing their stories, and at the end, a Congolese woman asked if American women were ever raped. Did they get the same kind of support she was getting, the woman asked.

“It was so powerful,” Williams says. “It shows how much more alike we are in this world than we are different. It was so stunning. That empathy.”

Williams’ July travel schedule took her to Congo for two weeks, then to Washington, D.C., then to Chicago, Minneapolis, and Montana. She makes a point to return to the state at least once every six weeks. And when Williams flies over Montana bound for another destination, she says she wishes she could ask the pilot to stop.

Williams’ name has come up as a potential candidate for statewide office. While her business must remain based in Seattle, she doesn’t have to. She says she’s open to running for office some day in Montana, but won’t commit beyond that. Still, she notes, it’s been almost 100 years since Montana sent the first woman to the U.S. Congress, and the state hasn’t elected one since.

We can’t, she says, let that go on much longer.