- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

There are only forty-two copies of The Workes of Geoffrey Chaucer, edited by John Stow, held in public institutions across the United States. Of the forty-two, a mere eleven reside west of the Mississippi. The University of Montana just happens to have one of them.

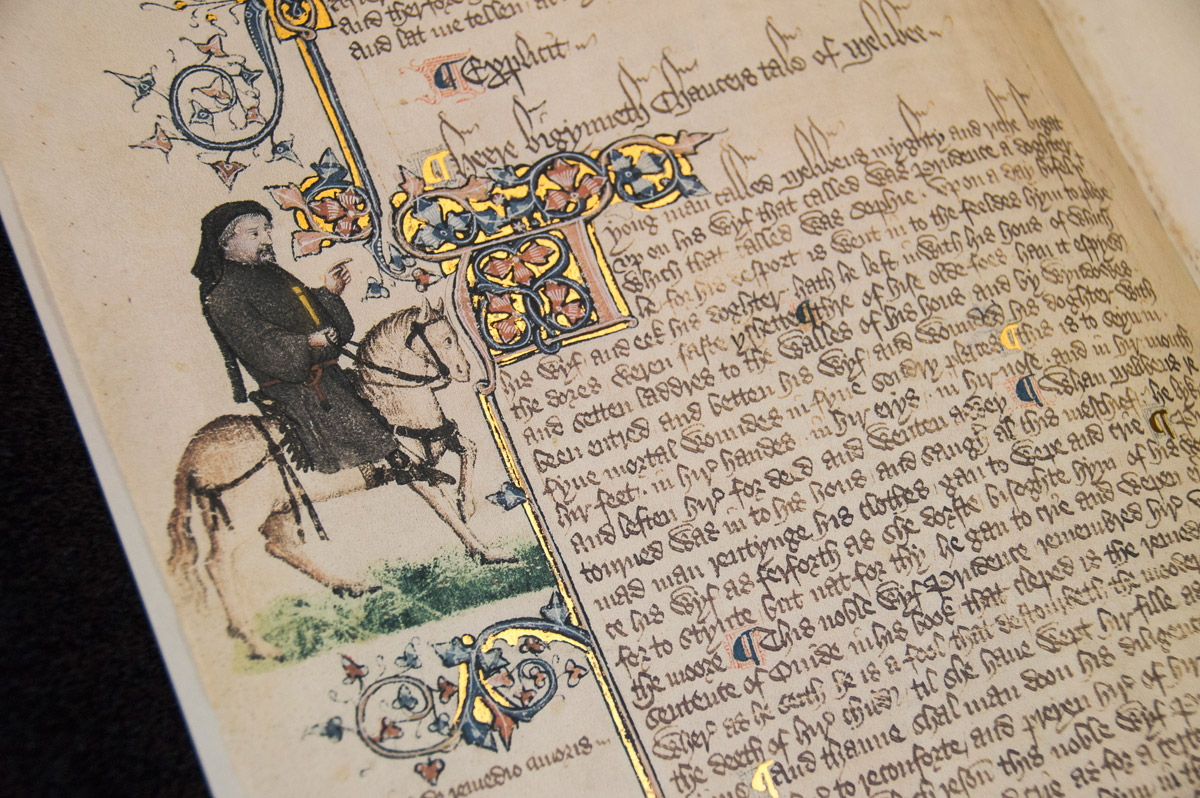

There are only forty-two copies of The Workes of Geoffrey Chaucer, edited by John Stow, held in public institutions across the United States. Of the forty-two, a mere eleven reside west of the Mississippi. The University of Montana just happens to have one of them. This particular edition dates back to 1561, making it the oldest complete book inside Archives & Special Collections at the Mansfield Library. And for being more than 450 years old, the book is in extraordinary condition. “It’s remarkable to look at because of the original paper, the look, and the feel of the book,” says UM Archivist Donna McCrea. “It’s also neat, of course, because of its age. For us, it’s simply irreplaceable.” The book, which includes The Canterbury Tales, was donated to the library by Richard Merritt, a 1948 English graduate. It first came into his hands in 1945 in Edinburgh, Scotland, and he paid £21 for it, which equated to $84 in U.S. currency. He held on to the book for nearly forty years before donating it to UM in 1983. It’s estimated to be worth around $50,000 today. It’s a critical piece of a surprisingly robust collection of Chauceriana at the library. “To have a collection like this in a low-population state like Montana is really incredible,” says UM Professor and Chaucer scholar Ashby Kinch. “I’ve had students who worked with the collection and went on to grad school at places that don’t have some of the materials they’ve looked at here. That’s something to be proud of.”

Chaucer, Kinch says, is without a doubt the single most important medieval English author. Known as the “Father of English Literature,” Chaucer’s early career focused on translating European continental literature written in Latin or French so it was available to English readers in their vernacular. His final and most famous project was The Canterbury Tales, which he worked on from the 1380s to his death in roughly 1400.

The library’s Chaucer collection has more than 1,500 items. About forty of the most rare and valuable—including originals or facsimiles of important editions representing all centuries from the fifteenth to the twentieth—are held in Archives & Special Collections.

“What makes this collection unique is the range,” Kinch says. “Students are able to have a broader context for Chaucer’s reception history—the way the text moves through time and is received in different cultures and in different periods of time.”

The newest addition to the collection, obtained this past fall, is a reproduction of the Ellesmere Manuscript, a beautiful, illuminated edition of The Canterbury Tales from the early fifteenth century. The original version of the Ellesmere is housed in the Huntington Library in San Marino, Calif.

“When I first saw the new facsimile, my eyes just popped,” Kinch says. “Real gold leaf is used in the illustrations, which gives it that feel and visual delight of a medieval manuscript. I’ve worked with dozens of real manuscripts in the British Library and in the Morgan Library in New York City, and I can tell you that this very closely resembles them. It’s fantastic. And to have students involved when we first opened it, that was a special moment.”

A majority of UM’s Chauceriana wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for generous gifts from Merritt and other donors. Purchasing the Ellesmere, which cost $8,000, was made possible by combining funds from the Lucia B. Mirrielees Memorial Fund, honoring the former UM English professor; the Davidson Honors College Opportunity Fund; and a gift in memory of Mabelle Hardy.

“In this virtual age,” Kinch says, “when we have access to digital images of manuscripts by the hundreds, students light up when they get in the presence of these books. When you hold the books in your hands, the text takes on a different meaning. Cognitively your brain lights up a different way than it does when you’re looking at a computer screen. A valuable part of an archive is that ability to make contact, through the book, with the hands that held this for hundreds of years. “You’re joining that lineage of hands, and you’re becoming a part of an actual physical legacy that stretches back in time.”