- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

In his new book, UM Professor Doug Emlen explains that from beetles to humans, animals develop weapons for similar reasons, with similar consequences

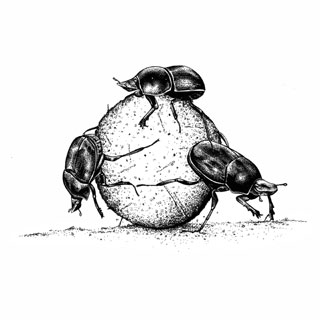

It’s not easy being a male Onthophagus nigriventris dung beetle.

When they’re not jostling for space around a pile of excrement, they’re trying to mate with females while ensuring no other male does the same.

It’s a relentless endeavor for which they’ve developed a helpful tool: weapons.

A gently arced horn extends forward from their thorax. While the females dig tunnels underneath the dung to stash poop and raise their young, the males follow them in to mate. But to protect their exclusivity in the gene pool, these males must

defend the narrow tunnels from rival suitors. They do so in a series of horn-to-horn duels, like medieval jousting matches. Predictably, the male with the largest horn wins.

It’s the evolutionary consequence of these duels that interests Doug Emlen, a biologist at the University of Montana and the world’s leading expert on beetle weaponry. When only the males with the biggest horns can mate, their offspring will grow similarly large horns. The biggest among those will then breed the most, creating an evolutionary arms race that leads to progressively larger horns.

On a recent snowy afternoon, I find Emlen burrowed into his office in the Biology

Research Building. He’s sitting at his desk in jeans, boots, and a plaid shirt, fielding phone calls and bearing the look of a man on a roll. I arrive as the phone rings with good news about a National Science Foundation grant that will fund his research for another three years. Another call finalizes the visa paperwork for a graduate student from France. He steals a glance at his computer monitor, perched atop an entomology textbook. Above it is the antlered skull of an African impala that he found in Africa as a kid. But perhaps the greatest single source of Emlen’s pride is at his feet: a box full of his freshly published book, Animal Weapons: The Evolution of Battle.

We’ve scarcely introduced ourselves when Emlen leans forward and asks: “So, do you want to see the beetles?”

We cross the hall to his laboratory, where several jars are filled with loamy soil. He doesn’t have a dung beetle on hand, but he opens one of the jars and shakes a Japanese rhinoceros beetle onto his palm. It’s beautiful: the size of a chicken egg, with a burnished chestnut back and an inch-long horn sticking out like a spatula from its forehead. Even after twenty years studying beetles, this specimen clearly delights Emlen. Beetles have more variation in horn size than in any other body part.

“The males with the biggest weapons win,” Emlen says. “It’s as simple as that.”

Emlen is drawn to outliers.

“I’m really interested in extremes,” he says. “I’m crazy about animals that look like they should not be possible.”

He grew up traipsing around the world with his ornithologist father, conducting fieldwork in Kenya, Panama, and elsewhere. Emlen’s grandfather was an ornithologist, too.

But the young Emlen? He rebelled.

“I loved insects,” he says. “And when you look at insects and you look for extremes, all arrows point to beetles.”

Some male beetles, for example, have horns so large that they account for a third of their body weight—the equivalent of a human wearing another leg on their head. Male stag beetles joust with a pair of toothed mandibles that can be longer than their bodies. Male harlequin beetles fight with their enormous forelimbs, which can span sixteen inches. When scaled to their overall size, few species in the animal kingdom come close to the sheer extravagance of beetle weaponry.

But until recently, Emlen was puzzled as to why some beetles developed weapons and others did not. Even among dung beetles, Emlen’s particular specialty, species with horns and species without horns can be found feeding on the same pile of poop. A massive swarm of beetles descending on a fresh pile of elephant dung in Tanzania one evening revealed the answer. Emlen and his students watched some species of beetles pack the dung into balls, which they rolled away to bury. These beetles fight above ground, and their confrontations are chaotic scrambles out in the open. Beetles without horns would be just as likely to win in these brawls as those with horns, so the males don’t waste the resources to develop weapons.

But the beetles that dig tunnels underneath the dung do develop weapons. Fights inside burrows unfold as orderly duels, and only the best-armed males mate with the females. Emlen saw that beetle weaponry required competition between males, a resource for them to defend, and a dueling fighting style. But Emlen knew that dung beetles weren’t the only creatures to benefit from weapons.

“It was a logical step to look into weapons on other animals,” he says. “Once I took that plunge, there was no going back. I was hooked.”

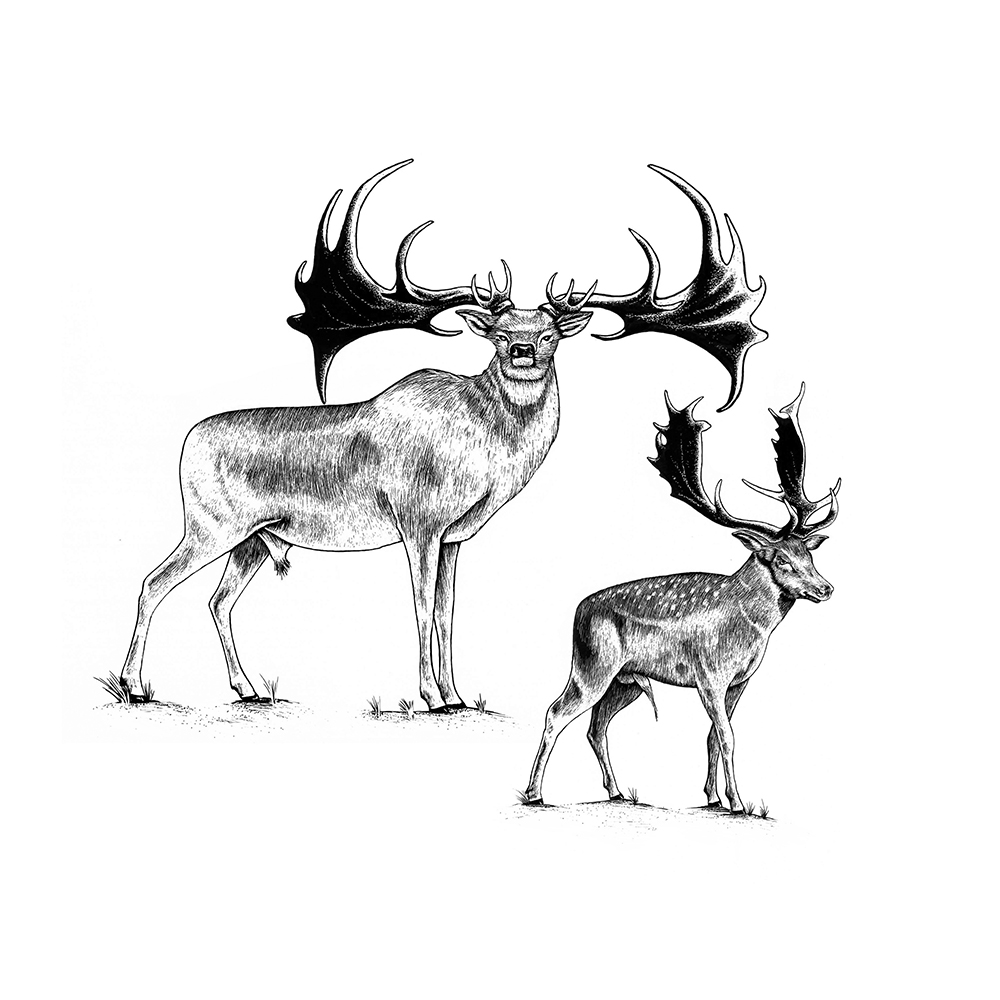

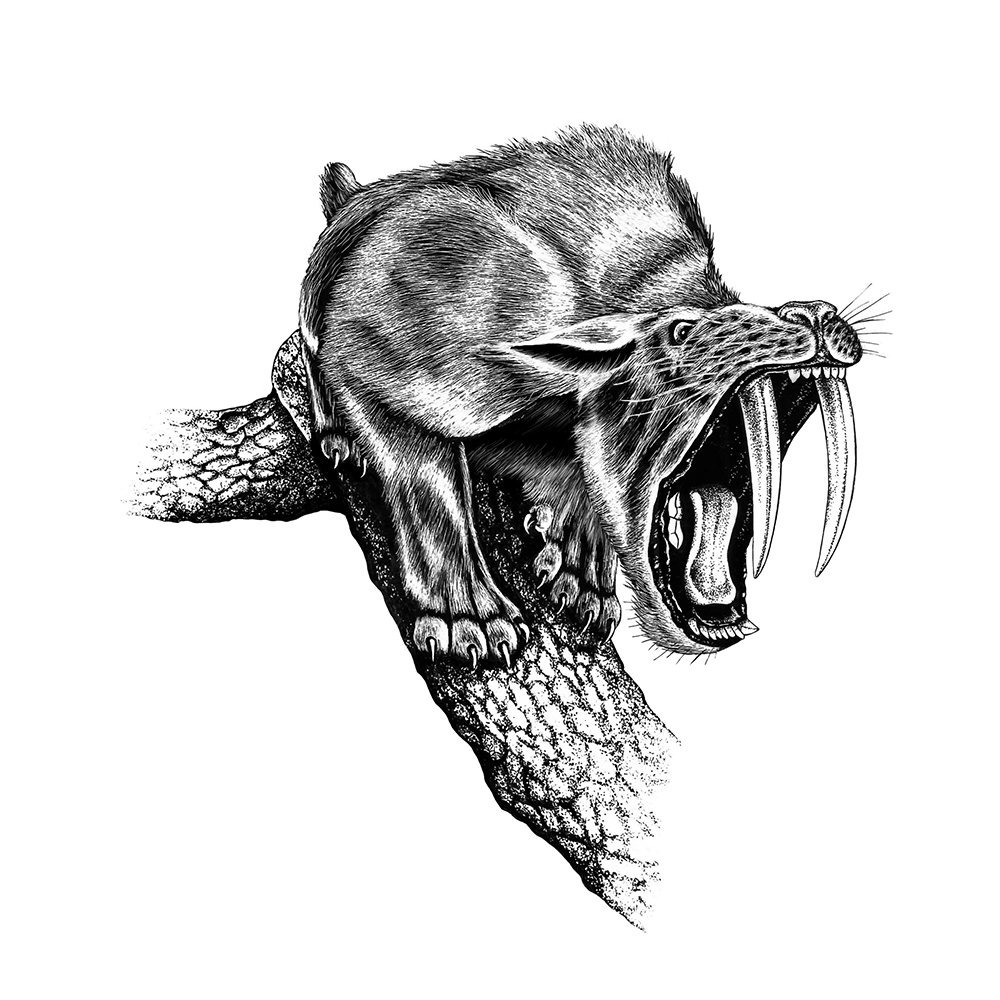

Emlen pored over research on animal weaponry. The scientific literature is replete with examples of extreme weapons. Columbian mammoth tusks stretched sixteen feet and weighed 200 pounds apiece. Sabertoothed cats ambushed their prey with ten-inch dagger canines that forced them to chew their kills out of the corners of their mouths. And the now-extinct Irish elk had antlers that were fourteen feet across.

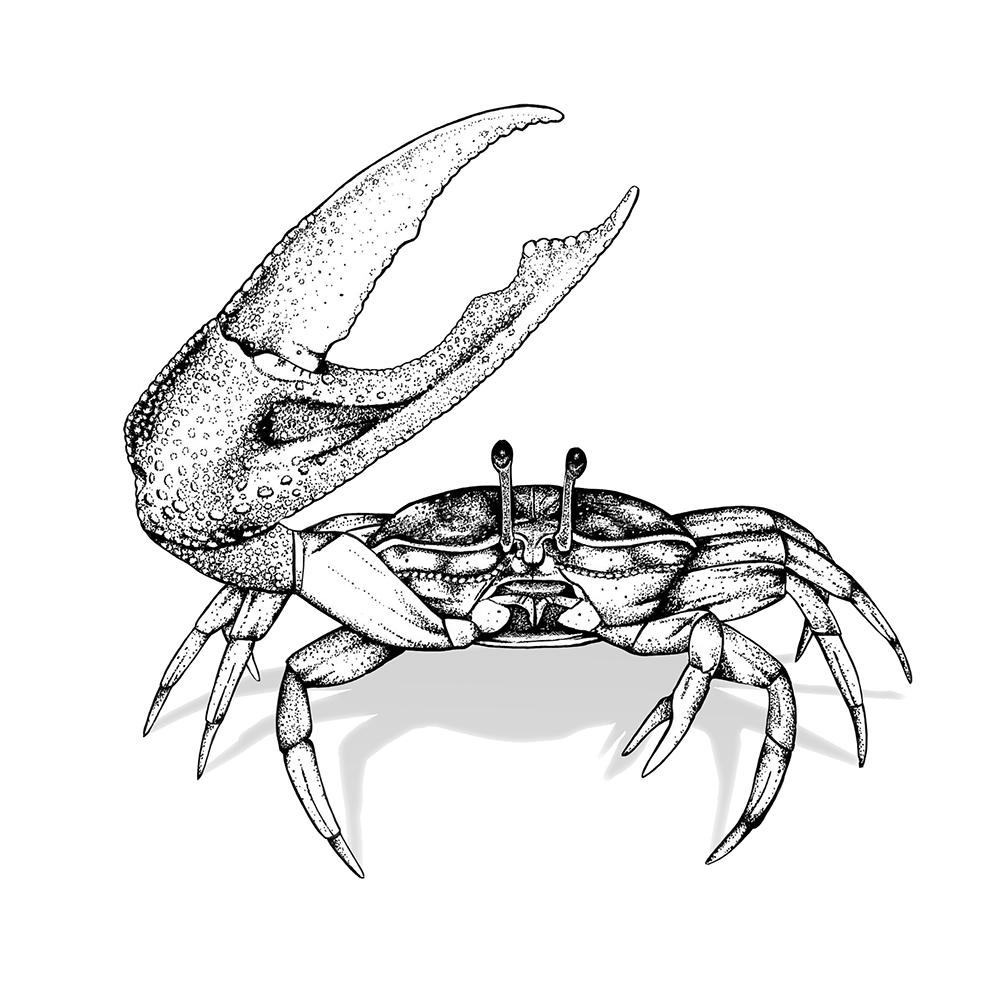

Present-day animals have elaborate weapons, too. Fiddler crabs grow one claw that is half the crab’s weight. The jaws of trap ants snap shut at 143 miles per hour. Fallow deer bucks have up to seventy tines across the perimeter of their antlers, which can spread more than nine feet wide. The antlers require so much calcium and phosphorus that the bucks leach the minerals from their bones, which results in a seasonal form of osteoporosis. Each new example thrilled Emlen.

“It got fun,” he says. “These are charismatic species. These aren’t cockroaches on a log. How is it possible that something that looks that absurd can survive and thrive?”

Emlen saw the opportunity to tell an engaging story about evolution to nonscientists. He found an agent, who found a publisher who liked the idea of a book on animal weapons for a general audience.

“This book was a chance to step back and look at the big picture,” Emlen says. “This is my attempt to make evolutionary biology exciting, relevant, and accessible to anybody.”

The more Emlen researched the evolutionary development of weapons in different species, the more commonalities he found.

“These aren’t separate stories,” he realized. “This is the same story.”

Then his editor suggested Emlen look into the history of weapon development in yet another animal—humans.

Emlen balked at first. He was a biologist, not a military historian. But the comparison intrigued him, and he saw some immediate parallels. The male dung beetles sparring in their tunnels reminded him of jousting knights, fighting to prove their valor to an eligible noblewoman. Emlen began brushing up on his military history, and he knew he was onto something when he found a book by Robert O’Connell, who had tried to explain weapon development through biological analogies.

“He was doing what I was doing, from the opposite side,” Emlen says. He learned conditions that create arms races among humans begin in the same ways they do with animals and are guided by similar rules.“

The pieces of the story lock,” Emlen says.

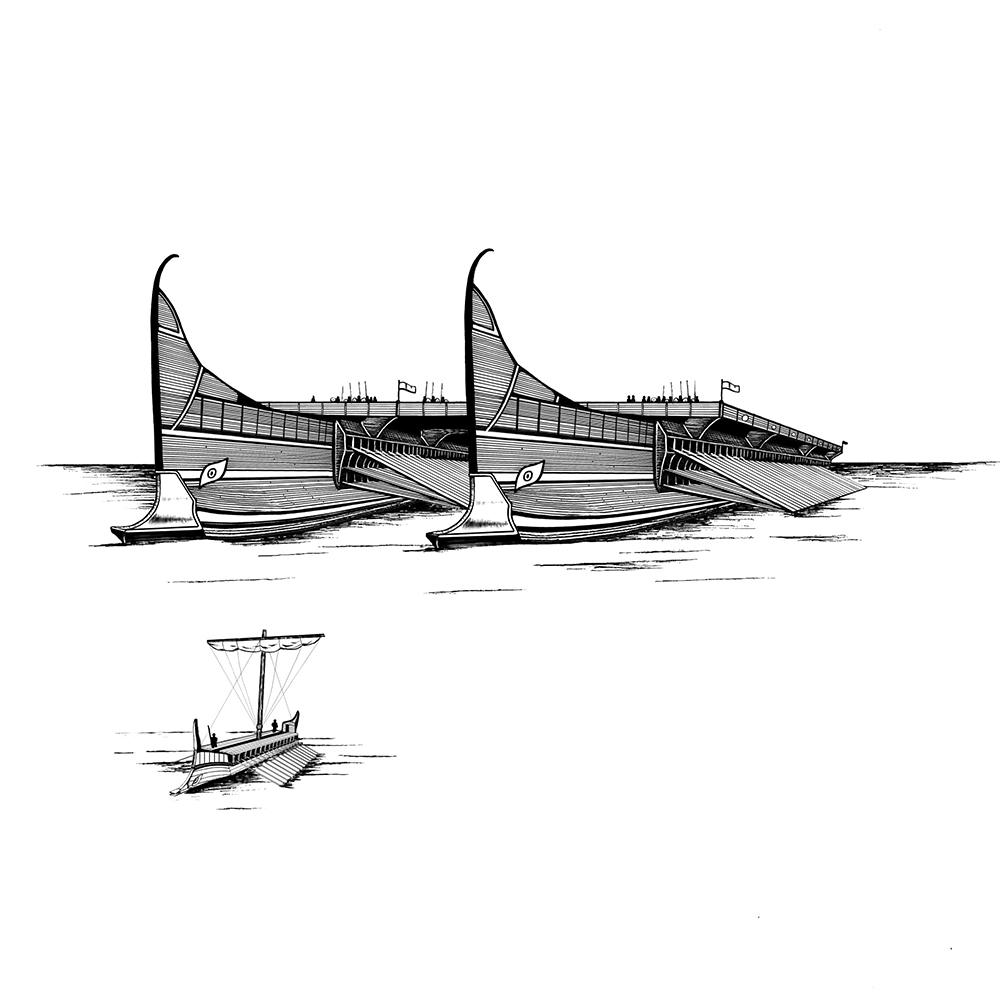

Take naval warfare, for example. In ancient times, oared galleys plied the Mediterranean, shuttling soldiers to battle as regional powers fought for supremacy. These boats remained relatively unchanged until about 750 B.C., when the wooden galleys acquired bronze battering rams. Now, instead of just transporting soldiers, the galleys could ram into each other like sparring bucks. Predictably, the bigger ship usually won. After the introduction of the battering ram, the Mediterranean witnessed one of the greatest naval arms races in history. Galleys grew from canoe-like vessels with twenty-five oarsmen per side to long, tiered ships rowed by 300 men. The biggest of all was 420 feet long and powered by 4,000 oarsmen—as extreme a weapon as ever there was.

“Big weapons get expensive,” Emlen says. “They do for beetles, and they do for us.”l arms races, though, this escalation had consequences. It meant that only the strongest, richest empires could compete, because few could afford the biggest vessels. And it strained the resources of even the wealthiest empires.Like al

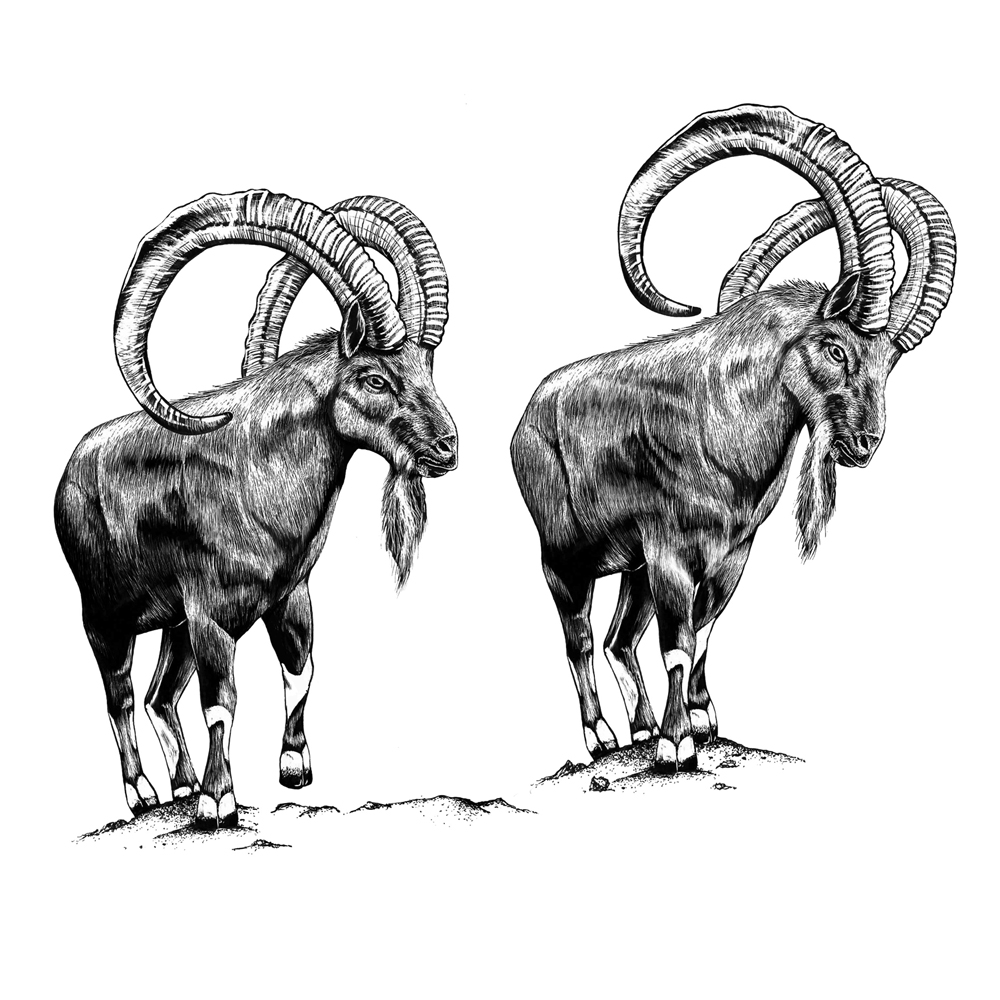

All animals face the same economic inhibition in their development of weapons. A bull caribou requires enormous energy to wield its five-foot-long antlers. A male dung beetle stunts its eyes, testes, and other organs to channel resources into growing its horn. These costs keep arms races from getting out of control, Emlen says. At some point, big weapons are more symbolic than practical. Ibex rams, for instance, have the longest horns of any ungulate, and they rarely fight. Males size up one another instead, backing down from a fight if they are inferior.

“Weapons become signals,” Emlen says. “They’re billboards of fighting ability.”

Humans have applied the same logic to the argument of nuclear deterrence. The Cold War is perhaps the most obvious human arms race that began as a duel between superpowers.

“Just like the biggest bull elk, these were the ones with the resources,” Emlen says.

In the end, the costs of the arms race exceeded the benefits for the USSR and the Cold War ended, leaving the USA as the world’s superpower—a lone bull with no challenger.

“I became convinced that we are safer because we have the biggest military and the best weapons on the block,” Emlen says.

There was just one part of his research that gave him pause: Not all male dung beetles play by the rules.

When Emlen applies this analogy to humans, his enthusiasm for the biology of extreme weapons gives way to concern.Most male Onthophagus nigriventris dung beetles spend their adult lives clashing horns for the privilege to mate with a female in the tunnels below a pile of dung. But some males don’t develop horns at all. These “cheater” males avoid confrontation with the bigger, horned males by digging their own tunnels, mating with the females, and slipping out undetected. Emlen calls it an “end run” around the constraints of the arms race, and it may have an evolutionary consequence. If a species’ weapons become too cumbersome or costly, and cheaters become more successful at mating, they could upend the arms race, changing the species forever.

“It makes me fearful,” he says

These days, conventional weapons such as submarines, jets, and aircraft carriers are so expensive that only wealthy countries can afford them. But weapons of mass destruction, on the other hand, are relatively cheap and aren’t always stockpiled securely. Some biological weapons can even be made in a basement laboratory.

“What if they get into the wrong hands?” Emlen wonders. “If those things are out there, and they’re cheap, they’re not like crab claws or beetle horns. They’re like the sneaky males mating with the females on the sly. It’s more like a scramble than a duel. It’s chaos.”

In short, the careful rules of the evolutionary arms race fall apart.

In Animal Weapons, Emlen compiles stories of animal weapons and their striking human parallels. The book is sprinkled with anecdotes from Emlen’s two decades of field research and includes detailed scientific illustrations by David Tuss, a UM alum. The book already is getting good reviews. Emlen recently went on National Public Radio’s Science Friday program to talk about it. He also wrote a piece about his research for The New York Times Magazine.

Emlen says that even after twenty years of research and writing papers, he’s never been more proud than he is of this book, even if the writing of it gave him some concern. It opens with Einstein’s ominous quote: “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

Toward the end of our interview, I ask Emlen if his research on animal weapons gives him hope or fear about the future of our own weapons.

“In the end, I got rather alarmed,” he tells me. “There is no animal precedent for a weapon of mass destruction.”

That chapter of our story, it seems, is still being written.

Jacob Baynham graduated from UM with a journalism degree in 2007. He writes for Outside, National Parks, and other magazines. He lives in Missoula with his wife, Hilly McGahan ’07, and their two sons.