- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

UM’s new Brain Initiative puts professors’ heads together to explore what’s inside them

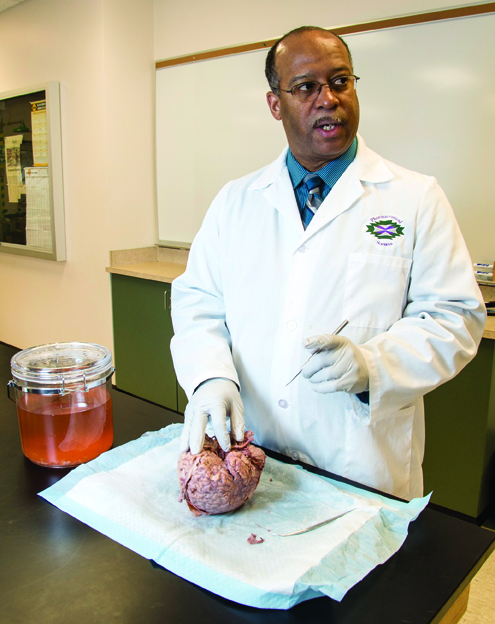

Darrell Jackson’s fascination with the brain began early—in junior high, to be precise, on a science-day field trip to the University of Washington School of Medicine. During that day he lost his classmates and found his calling.

“I’m one of those knuckleheads who will disappear from a group,” he says.

This particular day, he wandered up to the seventh-floor Department of Neurosurgery. Walking around, he saw laboratories full of scientists and doctors in white coats. They were conducting research on epilepsy in Rhesus monkeys, he would later learn, studying the patterns of their brain waves during seizures.

A surgical tech found Jackson wandering the halls. Jackson gushed about how interesting the research looked. “If you really are interested,” the tech told him, “come back. We’ll put you to work.”

And so he did. He had to catch two buses to get there from his home in West Seattle, but he worked in the labs on weekends and holidays all through high school except during football season. He worked with monkeys, cats, and rabbits, studying how their brains responded to seizures and how nerve cells could regenerate after being damaged.

“It was just completely fascinating,” he says. “I’ve always been interested in the brain itself. Like a kid who takes apart a toaster, I wanted to know how it worked.”

Thirty odd years later, Jackson is a professor in the University of Montana’s Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, with labs of his own. He walks into one of them on a recent Friday, unlocks a chained cupboard door, and withdraws a sealed specimen jar the size of an ice-cream tub. It’s not much to look at. But there, bobbing in peach-colored preservative, is the wrinkled, three-pound object of Jackson’s lifelong curiosity: a human brain. Jackson admires it for a moment, lighting up like he’s back in the seventh grade, lost on a field trip.

“Every square inch has a function,” he says. “I still don’t know how it works to this day. I know a lot more. But I still don’t know.”

Jackson’s fascination is hardly unique. Scientists have been captivated by the brain for centuries, but like Jackson, the more they learn about the enigmatic organ, the more they realize they don’t know. Brain research has enjoyed a recent renaissance in America. Last year, President Barack Obama announced an ambitious new proposal to map every neuron in the brain in the spirit of the Human Genome Project. The sporting world increasingly is interested in the way concussions effect athletes’ brains. And veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are coming home with unprecedented rates of traumatic brain injury. Unraveling the riddles of the brain is more urgent than ever.

This February, Provost Perry Brown threw the University’s hat in the ring with the announcement of the new Brain Initiative. UM already is known for the bench research it conducts through the Montana Neuroscience Institute, a collaboration with St. Patrick Hospital, and the National Institutes of Health-funded Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience. But this new project would consolidate brain research from across the University.

“Through this Brain Initiative,” Brown told an audience on UM’s Charter Day, “we’ll bring together people from across campus to expand the research we have.”

Under Jackson’s directorship, the initiative will set up a website to educate Montanans on the brain research happening on campus. It will reach out to the community through exhibits in spectrUM Discovery Area’s children’s science center, for example, where Jackson hopes kids like he was will be inspired to pursue careers in neuroscience. The initiative also will establish an undergraduate degree in neuroscience, which student surveys show will have high demand. And in March, the Board of Regents approved a new Neural Injury Center to help students with traumatic brain injuries access services across campus.

But more than anything, the Brain Initiative exposes just how diverse UM’s brain research is. It turns out Jackson’s fascination is shared by professors in all corners of campus—from laboratories in the Skaggs Building to clinics at Curry Health Center to the stages of the College of Visual and Performing Arts. Our brains are responsible for everything we do, think, or perceive. So it stands to reason that faculty from vastly different disciplines approach it with angles all their own.

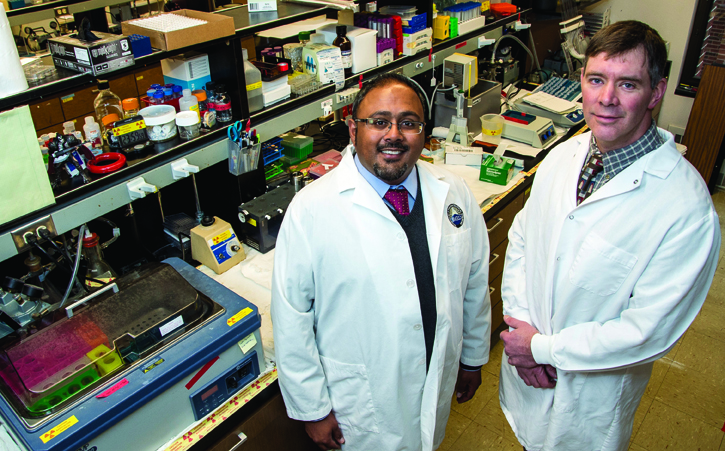

Sarj Patel and Tom Rau’s angle is concussions.

Earlier this year, the two UM research professors received a competitive $300,000 grant from the National Football League and GE’s Head Health Challenge, a $10 million venture to support brain injury research. Patel and Rau study proteins in the brain and microRNA molecules in the blood that may indicate the existence and severity of a traumatic brain injury. Today, the standard test for a concussion is a panel of questions that a coach might ask of a player, for example, on the sideline of a football game. The resulting diagnoses are inconsistent and poor at detecting low-level injuries. Patel hopes that team medics may eventually be able to draw a player’s blood, check it for the biomarker molecules, and determine if he has a concussion and how bad it is. Patel and Rau have studied these proteins in rats, and also in human blood and brain tissue, thanks to partnerships with the emergency room at St. Patrick Hospital and the Center for Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University. Patel s

In and out of the lab, Patel and Rau share an earthy appreciation for the focus of their research.ays they’ve been discussing a collaboration with UM’s athletic department, too.

“Your brain is basically like a formed piece of fatty Jell-O suspended in a protective water bath,” Rau says.

But for humans, our biggest biological advantage—a large brain—also is a liability. A head still has to be small enough to fit through the birth canal, Rau explains. In order to maximize brain size, our skulls are thinner than most primates.

“You hit a gorilla on the head with a sledgehammer, and they’ll just stare at you,” Rau says. “Before they kill you.”

The human brain is a bit more fragile, and Patel and Rau are busily applying theirs to better protect ours. In the process, they’re putting UM on the brain research map alongside larger institutions.

It creates this forum for people who have similar interests. That it occurs on a campus with a long tradition of liberal arts is fortuitous, considering that the brain has right and left hemispheres.

“Translating basic science research to the clinic can be difficult when we don’t have a medical school,” Rau says. “But with the cooperation of the University and local hospitals, we’re able to move our findings from the lab into clinical research.”

Traumatic brain injury isn’t limited to football, of course. Three floors down from Rau and Patel, Reed Humphrey just received approval to create a Neural Injury Center to help veterans and other students with brain injuries access the resources they need to cope with their disabilities and make the most of their time on campus. The center is especially relevant in Montana, a state with the second highest per capita rate of brain injury in the country.

Before coming to UM, where he chairs the School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science, Humphrey treated patients at the VA Medical Center in Richmond, Va., while on faculty at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“I really got an appreciation for the hardships veterans face reintegrating into society,” he says.

In addition to PTSD, many veterans return with some degree of traumatic brain injury, often incurred from an improvised explosive device. Through the Neural Injury Center, Humphrey hopes to create a more supportive environment for veterans on campus.

“The goal is to serve those who have served us,” he says.

The NIC’s first task is to create an interactive Web presence, which Humphrey is doing in collaboration with the School of Media Arts. The website, which he expects to launch this summer, will engage students who have experienced a brain injury, directing them to campus services that tend to their physical and emotional health, their family life, career opportunities, and education.

“The idea is to create a campus that is welcoming to people with a disability,” Humphrey says. “If we do this right, we’ll attract students throughout the region and nationally.”

The NIC brings form and function to the Brain Initiative, Humphrey says. In turn, the initiative has introduced Humphrey to pockets of brain research going on around campus that he wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

“It creates this forum for people who have similar interests,” Humphrey says. “That it occurs on a campus with a long tradition of liberal arts is fortuitous, considering that the brain has right and left hemispheres.”

If the neuroscience labs of the Skaggs Building represent the left side of UM’s brain research, the right side of that research can be found in Jillian Campana’s comfortable office in the College of Visual and Performing Arts.

Campana teaches acting and directing classes, but her true interest is applied theater—using drama to promote social justice, therapy, or rehabilitation. Her specialty is designing theater workshops for people with traumatic or acquired brain injuries. Every year for the past decade, she’s traveled to a holistic rehabilitation center in Sweden to help people recover from strokes or head injuries.

“People are very different after a brain injury,” Campana explains. “Often they don’t have people help them know how they’ve changed, who they want to become, and how they want to be perceived.”

Acting can help answer those questions, she says. The stage offers a safe environment to try out different emotions without consequences. It helps survivors learn to speak again, to better coordinate their bodies, and to regenerate their sense of selves. Campana worked with one young woman who suffered a traumatic brain injury in a skiing accident. The woman was in a wheelchair but hoped to walk again. She was able to stand, occasionally, but hadn’t taken any steps since the accident. During the course of the workshop, Campana noticed her mobility increase. Eventually, with two people at her side, she was able to take eight or nine steps.

“I’m not saying that theater made her muscles move,” Campana says. “I’m saying because of the drama exercises, she believed she could do it and had the courage to try. There’s something very empowering about the magic of inhabiting another person through acting.”

For Campana, the work is personal. Fourteen years ago she suffered a stroke herself. The damage wasn’t cognitive—she’s grateful for that—but it left Campana able to move only the tip of her finger.

“I had to learn everything,” she says. “How to put a spoon to my mouth, how to brush my hair.”

Physical therapists lowered her into a swimming pool and taught her to walk again. Less than a year after the stroke, she was able to walk down the aisle in her wedding, without a cane. Years later, she ran the Chicago Marathon. She still has no feeling on her left side, but she feels fortunate to have recovered as quickly and fully as she did.

The experience fuels the work she does today. In spring 2015, she’ll teach a course in applied theater—a class geared toward students outside of the arts who would like to apply drama to psychology, social sciences, education, neuroscience, and other disciplines. For now, she’s excited to be learning about the brain research going on around campus. She hopes the Brain Initiative will enable her to measure the efficacy of applied theater in restoring the physical and psychological health of stroke survivors. She has enjoyed talking to professors from other disciplines about her work.

“It’s very encouraging for me that faculty are interested that an art form can improve the life of a person who’s experienced trauma,” Campana says. “It can help them heal and become who they want to be.”

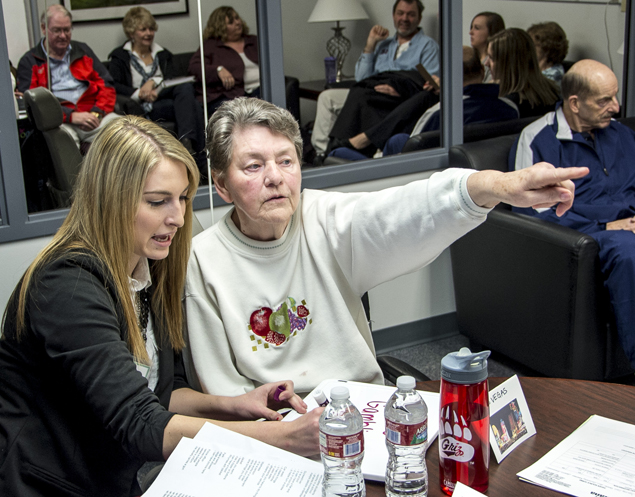

Across campus, in the basement of the Curry Health Center, Catherine Off helps people become who they want to be by helping them say what they want to say.

A speech pathologist, Off directs the Big Sky Aphasia Program with her colleague Annie Kennedy. Together they coordinate intensive speech therapy for victims of strokes, traumatic brain injuries, and degenerative illnesses. The power of speech, Off says, is a complicated cognitive and physical process most people take for granted. In order to say “book,” for example, our brains must summon our memory of the object, recall the word for that object, and then assign the mouth and tongue to vocalize that word—in milliseconds.

“It’s kind of unbelievable that we do it with such success,” Off says.

When that ability is impaired by a brain injury, however, a person can feel like they’re stranded in a foreign country, struggling to string together the right words in the right order.

“A lot of people withdraw,” Off says. “It’s an instinct when you can’t communicate. Our goal is to get them back out there.”

The Big Sky Aphasia Program offers two intensive clinics each year, in summer and fall, where six to eight patients receive speech therapy in groups and one-on-one. There are only three or four programs like it in the country.

Throughout the academic year, Off and her colleagues run clinics where students in the Department of Communicative Sciences and Disorders [part of the Phyllis J. Washington College of Education and Human Sciences] get firsthand experience working with patients. Off monitors their interaction with patients via remote camera or a two-way mirror.

The communicative sciences and disorders department recently was revived after a twenty-year hiatus, and Off is glad to be training the next generation of Montana’s speech pathologists. Watching them work with patients reminds her why she entered the field and exemplifies the potential of UM’s Brain Initiative, which is establishing synapses among faculty across campus to apply and share their diverse understandings of our most complex organ.

“I’ve always been drawn to people who have undergone some sort of life-changing event,” Off says. “I still love meeting a client for the first time before I know anything about them. I’ve never met two clients who are the same. No two people think exactly the same way.”

Jacob Baynham graduated from UM with a journalism degree in 2007. He writes for Outside, National Parks, and other magazines. He lives in Missoula with his wife, Hilly McGahan ’07, and their two sons.