- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

In a wide array of studies, UM’s HHP Department makes significant impacts on the well-being of the people of Montana and beyond

Annie Sondag’s current work with HIV prevention in Montana began in an unlikely place: an airport bar in San Diego. It was 1994, and Sondag was a newly minted University of Montana professor of health education on her way back to the Treasure State from a conference. Sitting inside the bar amid chatter and clinking cocktail glasses, she overheard a group from the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services discussing new HIV funding for the state. Sondag was intrigued. As it turned out, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had just given out a chunk of money to every state with the goal that each could use it to tailor its own prevention program. It was exciting news, but it would require some heavy lifting.

“Here was a group who had a big grant, and they were struggling with how to do an evaluation of their programs,” Sondag says. “I was not very experienced, but I knew about evaluation. I walked up to them and said, ‘I can help you,’ thinking I could help them out for free. I was relatively new, and I needed the experience. And they said, ‘Yes.’”

In fact, the chance encounter in the airport marked a shift in Sondag’s trajectory. Prevention became her calling. During the past two decades, her work at UM has helped the state facilitate a multitude of important HIV prevention programs. That work evolved to encompass the most progressive philosophies on what community health means and who is most at risk for poor health outcomes. In a larger context, she’s trying to effect positive change in the world through the avenue of health education and promotion.

And, on UM’s campus, she’s not alone.

Sondag is part of an exciting UM department focusing on making people healthier and, by extension, happier. UM’s Department of Health and Human Performance, housed within the Phyllis J. Washington College of Education and Human Sciences, centers on three distinct programs: community health, exercise science, and health enhancement. It’s currently one of UM’s most popular departments of academic study, ranking second in students enrolled.

Its wide range of classes reflects a broad but timelessly vital mission: “To advance the physical, emotional, and intellectual health of a diverse society.”

Sondag’s HIV prevention work is a perfect example of how academic programs like UM’s HHP department have evolved to adjust to that mission. In the years after 1981, when the CDC first reported HIV/AIDS cases in the U.S., prevention was focused on changing individual behaviors.

“At the beginning of the epidemic, it was scary—nobody really knew how the virus was transmitted,” Sondag says. “Once people knew how to protect themselves, transmission rates fell dramatically in the first ten years. But then we had this group of people who weren’t changing their behaviors ... those are populations who often are disadvantaged and stigmatized, who—despite knowing how to prevent HIV—don’t always have the resources to necessarily do that.”

Sondag and her graduate students recently collaborated with the Gender Expansion Project, led by Bree Sutherland and Laurie Kops at the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, to assess the health needs of Montana’s transgender community. The first phase, Trans* in the Big Sky: A PhotoVoice Project, uses interviews and PhotoVoice—a group analysis method combining photography with grassroots social action—to examine factors that influence transgender individuals’ quality of life, such as sense of self, access to health care, legal issues, and love. The second phase of the project currently is in progress: distributing a comprehensive nationwide questionnaire for transgender individuals, which also aims to identify factors that put them at risk for infection with HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and Hepatitis C.

“I'm hoping that people who are trans will realize that by participating in our research they are going to make the road less bumpy for people to come out as trans,” Sondag says. “I think that the more we show the photographs and we tell the stories about people who are transgender, the more other people are going to say, ‘Wow, they are just like us.’”

Matt Bundle was first inspired by the famous Harvard physiologist C. Richard Taylor, known for, among other things, putting wild animals on treadmills to study their locomotion and design. Bundle was an undergrad at Harvard in the mid-1990s and captain of the school’s track and field team when he heard about Taylor’s work. He decided to take some classes from him, though he had no intention of making a career out of it.

“The connection between movement and anatomy and physiology felt to me, at the time, a tremendous marriage of my interests,” Bundle says. “But I had no idea that people pursued it as a legitimate course of study.”

Earlier in his career, Taylor worked in Africa experimenting with how variables change in animals of different sizes and how they maintain body temperature in some of the hottest climes on Earth. Bundle recalls the 16 mm films they watched in class showing Taylor in a Sherlock Holmes-style hat chasing wild African animals around a pen as they were hooked up to metabolic machines. Bundle went on to work in Taylor’s laboratory at the Concord Field Station in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

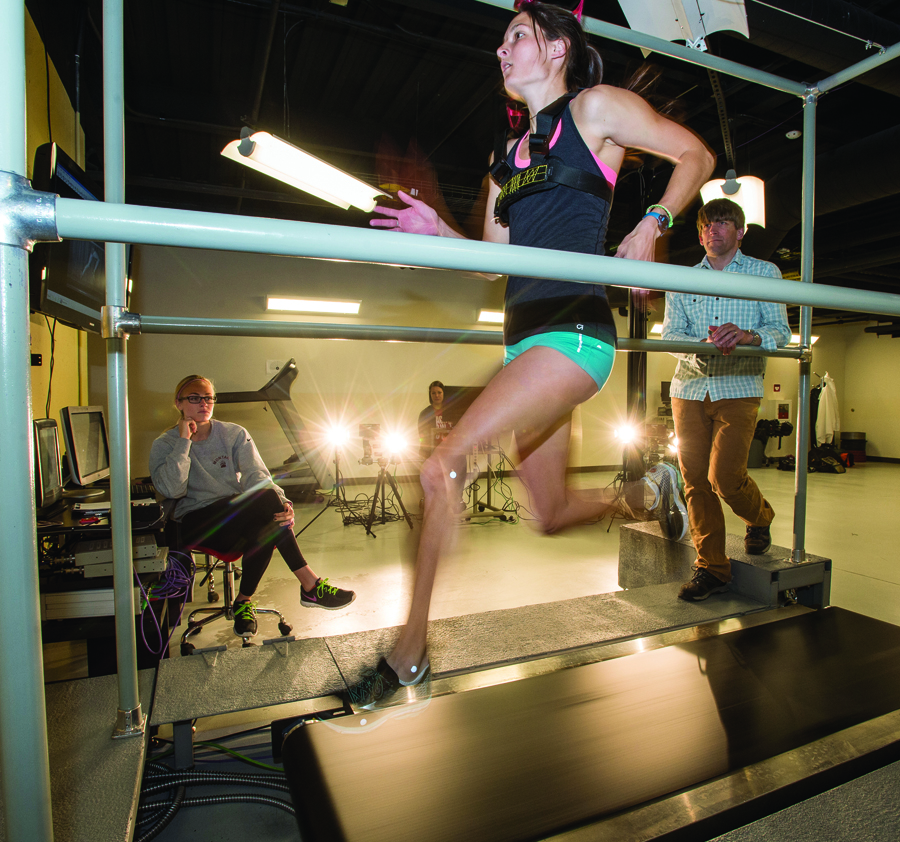

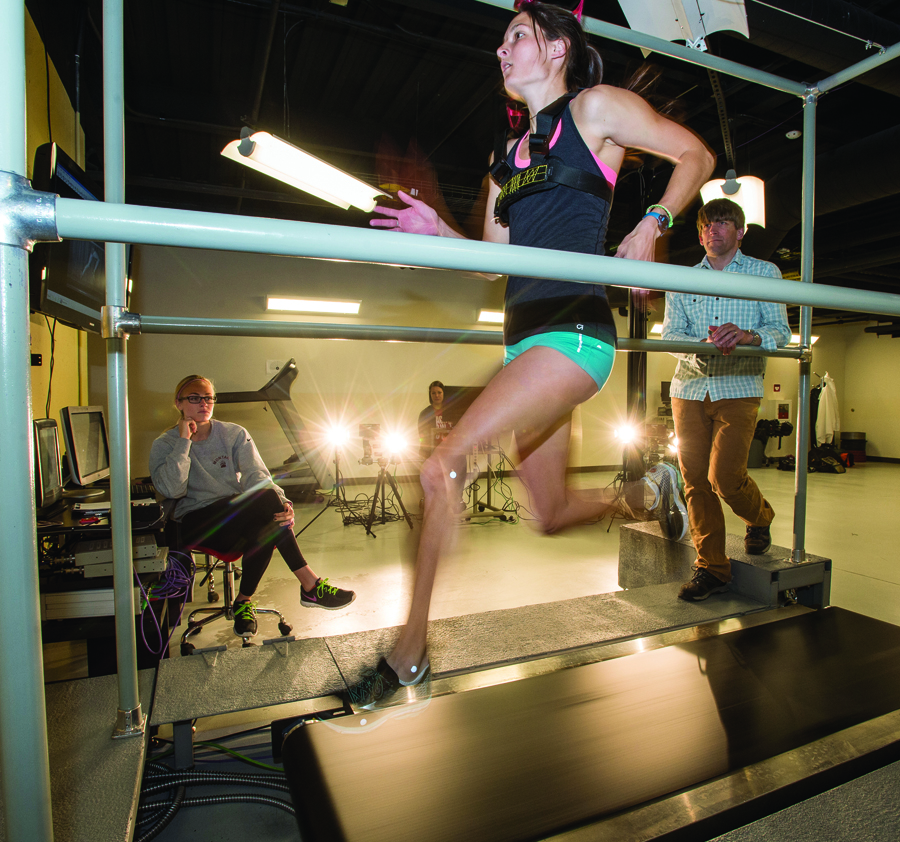

Now an exercise science professor at UM, Bundle has his own laboratory where he studies the way human bodies work. Inside the basement of the Phyllis J. Washington Education Center, you can find what looks like a futuristic fitness gym: a stationary bike hooked up to machines; a custom ergometer that looks half-weight machine, half bike; and an oversized treadmill.

There are no wild antelope, but you might find a Montana Grizzly athlete racing across the conveyer belt. This treadmill is one of two in the world that can measure the force of weight each footfall creates at the limit of human gait and speed.

And it helps to examine one of the many mysteries of the human body.

“If your event specialty is 60 meters or 100 meters and you’ve had competitive success, you would be able to typically throw about five times your body weight each step—peak, not average—against the ground,” Bundle says. “But we could take this person over to the gym and load up five-times the body’s weight and there will be no way they can support it. And so this is one of the things we are interested in. It’s a basic neuromuscular question about how we do it.”

Bundle, who got his doctorate in biology from UM and a postdoctoral degree at Rice University, returned to UM to teach three years ago. By then he had made news: He and a colleague made waves with their work proving double-amputee Olympic runner Oscar Pistorius had a clear advantage with his prosthetic legs over other runners.

He is one of UM’s many HHP professors in the exercise science program exploring questions about the science of the human body. It focuses on three tracks: the preprofessional track, which often leads to careers in medicine and physical therapy; the applied track, which prepares students to be fitness trainers; and the pre-athletic track, which preps undergrads for athletic training degrees that can lead to work in collegiate and professional sports.

The work students do is far from insular. This year marks fifty years of consulting with the U.S. Forest Service on health and performance issues for wildland firefighters. Students also work with UM’s physical therapy program, as well as off-campus programs such as the International Heart Institute of Montana and engineering companies. As part of HHP’s Exercise, Aging, and Disease class, students have helped alert faculty and staff members of their own health issues.

“It’s a great integrative approach where they get to use a lot of the information they have been studying,” Bundle says. “They bring in people from the University community, some of whom are at risk for coronary events, and work with them to make a positive change.”

Though Bundle’s career first was driven by a fascination with athletic performance, almost everything he does with his students also has promise for the health of average humans.

“The exercise science faculty are broadly interested in the health benefits of exercise,” Bundle says. “I look at how legs are designed and what that means for things like stiffness and how much compression should be happening. That can inform the development of new techniques for people who want to run faster, or inform the design of shoes, or the design of prostheses. But all these elements can improve ambulation, physical activity, and the health of different segments of our population.”

In so many movies about high school life—i.e., every John Hughes’ movie—physical education gets a bad rap. It’s the quintessentially hated class for computer geeks and artsy misfits, partly because it favors star athletes and partly because it doesn’t inspire students who aren’t interested in organized sports.

In UM’s HHP department, students are learning how to teach “health enhancement”—what used to be called “P.E.” It’s physical education taught in a more holistic fashion, with an emphasis on healthy lifestyle.

Shanel Curtis is a nontraditional student studying health enhancement in the hopes of teaching grade-school kids. She says the program offers a much-needed update if society wants to turn the tide for a country that is increasingly unhealthy.

“P.E. teachers can really end up focusing on that 3 percent of the class that runs really well and ignore the other 97 percent of their students,” Curtis says.

Curtis didn’t always want to work with kids. She got her first degree from UM in culinary arts and cooked while enlisted in the Navy. Working with food got her thinking about nutrition, and she thought helping people choose a healthy diet would be one way to make a difference. Initially, she was interested in community health for senior citizens, so when she enrolled at UM on the G.I. Bill, she took a class in gerontology. But as much as she enjoyed her time with an older demographic, she also was frustrated with the work.

“I like older people a lot,” Curtis says, “but it was depressing sometimes, simply because when someone has been doing one thing for eighty years, it’s hard to get them to switch their lifestyle—as opposed to a school-aged child.

I decided I’d rather make some kind of impact with people early on in their lives, where I could actually make a difference for them when they do get older.”

The classes Curtis takes reflect the well-rounded philosophy of health enhancement. Applied anatomy and kinesiology, developmental psychology, and nutrition go hand-in-hand with outdoor and indoor activities such as learning how to teach soccer, swing dancing, or volleyball. But some of the more interesting classes teach innovative methods for elementary P.E. that shift the focus from athleticism and presidential fitness standards to activities that kids can do for a lifetime. For instance, a teacher might set up an obstacle course where students must use a map and compass to get through it.

“It’s about incorporating some other skills—a little math, a little bit of science—and then they’re walking and using up their whole class period being active,” Curtis says. “Sometimes P.E. is the only place they get to be active.”

So far, the research project Annie Sondag and partners are working on supports an incredibly important idea in community health: Prevention isn’t just about telling people to eat better, or practice safe sex, or exercise. If a group is stigmatized, other social factors—like poverty—come into play.

“If you were to look at different populations of people and predict who is most likely to die younger and experience more illness in their lifetime,” Sondag says, “the thing many social scientists say most predicts that is poverty.”

That idea of equal access is one that roots itself deep into UM's health education philosophies—for all kinds of populations. Sondag’s colleague Professor Blakely Brown works with a variety of people, including Native Americans, building afterschool programs and community gardens. Another colleague, Laura Dybdal, does mind-body work with veterans who don’t always have access to therapeutic outlets for stress.

In the larger scope, the entire HHP program is about approaching health from all angles that matter, based on the best research out there.

“We have to change the environment around people,” Sondag says. “We have to change the norms if we want to see positive change on a community level. And we have, as a department, a common focus: keeping people healthy—and that has to happen in a multitude of ways.”