- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

To measure how tall Dr. Jack Burgess ’43 stood, look no further than The Secret Game he played in an empty gym in 1944

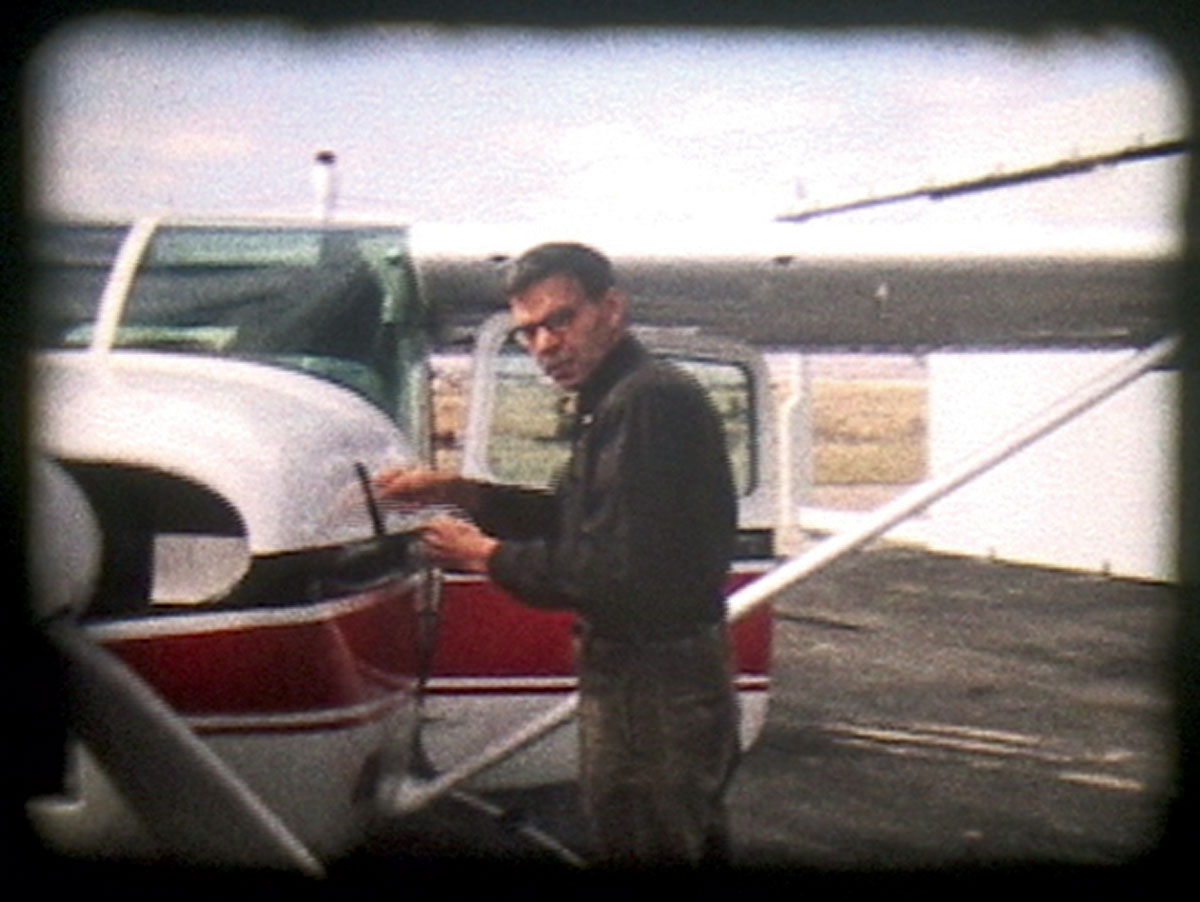

The four-seat Cessna 210, engine purring, turned onto the runway at Helena Regional Airport and gained speed, nosing into the air. It was 2002, and inside the plane were pilot Jack Burgess, co-pilot Jeff Morrison, and Burgess’ daughter, Eileen Watson.

The four-seat Cessna 210, engine purring, turned onto the runway at Helena Regional Airport and gained speed, nosing into the air. It was 2002, and inside the plane were pilot Jack Burgess, co-pilot Jeff Morrison, and Burgess’ daughter, Eileen Watson.

It was Burgess’ last flight. He was seventy-nine, struggling to see, and too infirm to fly much longer. They were taking the Cessna to a buyer in Great Falls.

From her seat, Eileen could see the finality of the act on her father’s face.

“It was an emotional time,” she says.

Burgess was a physician who’d settled in Helena in 1956 after a couple of years in Townsend. The former University of Montana basketball player retired in 1984. Well, not really.

He worked as Mountain Bell’s medical director for another five years, and when that ended, he still volunteered at the Leo Pocha Health Clinic he helped start in Helena, and at the clinic in Seeley Lake, near his cabin.

That cabin, on the shores of Placid Lake, was his Xanadu: A place to relax and weld artwork after he gave up his rounds. His family spent summers there, and on Thursdays when he still practiced medicine, he would fly up from Helena, announcing his arrival with a pass directly over the roof.

No more of that, now. The plane was being sold. He had looked down and seen his kids on the boathouse, furiously waving beach towels, for the last time.

Hoop Dreams

Of the many remarkable things Jack Burgess did in his eighty years on Earth, playing in The Secret Game clearly stands out.

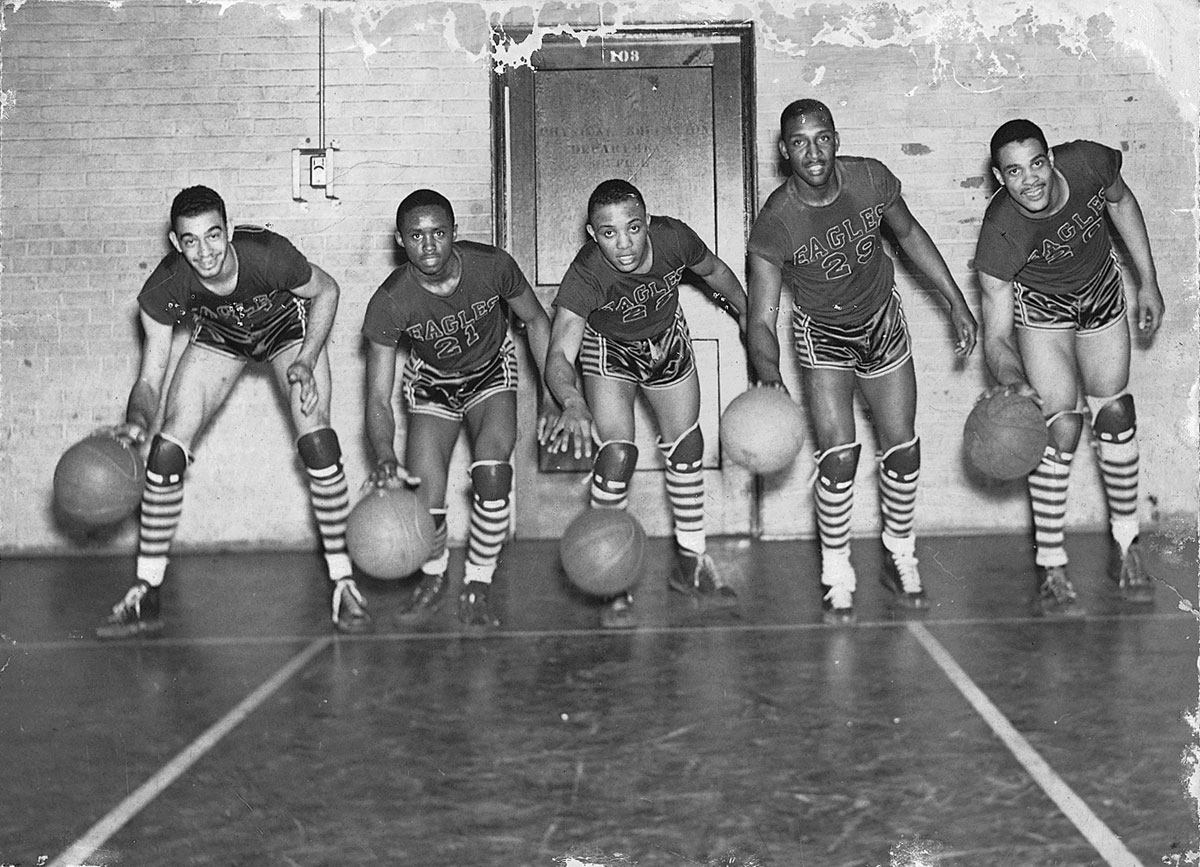

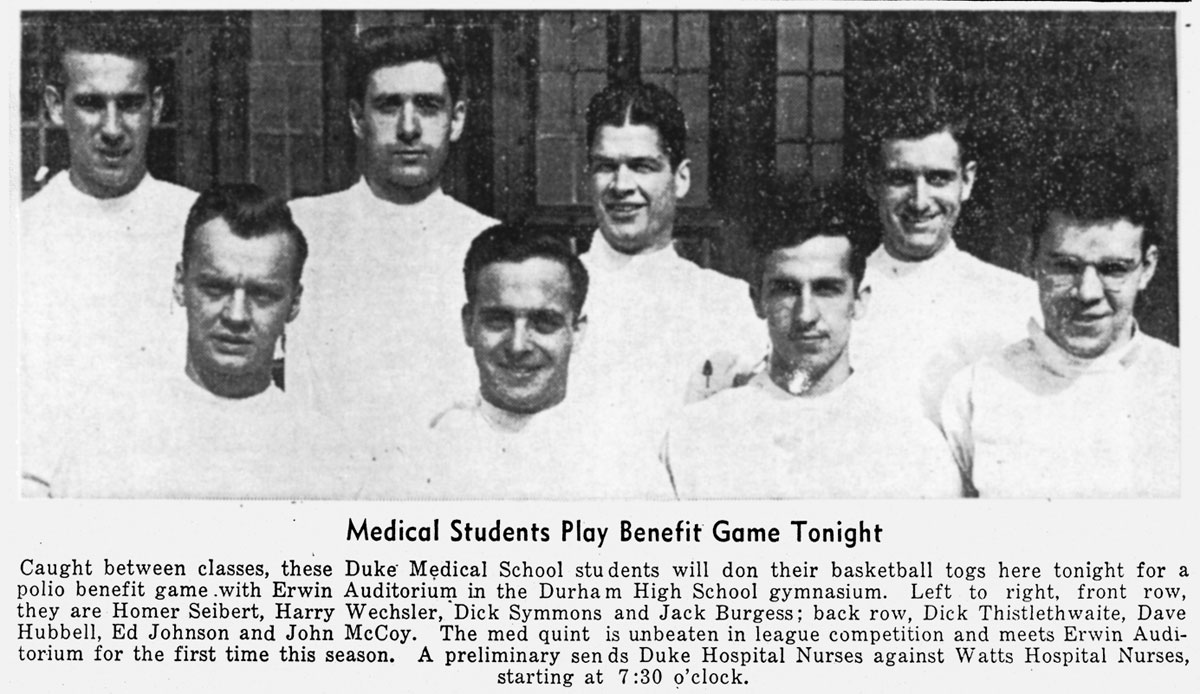

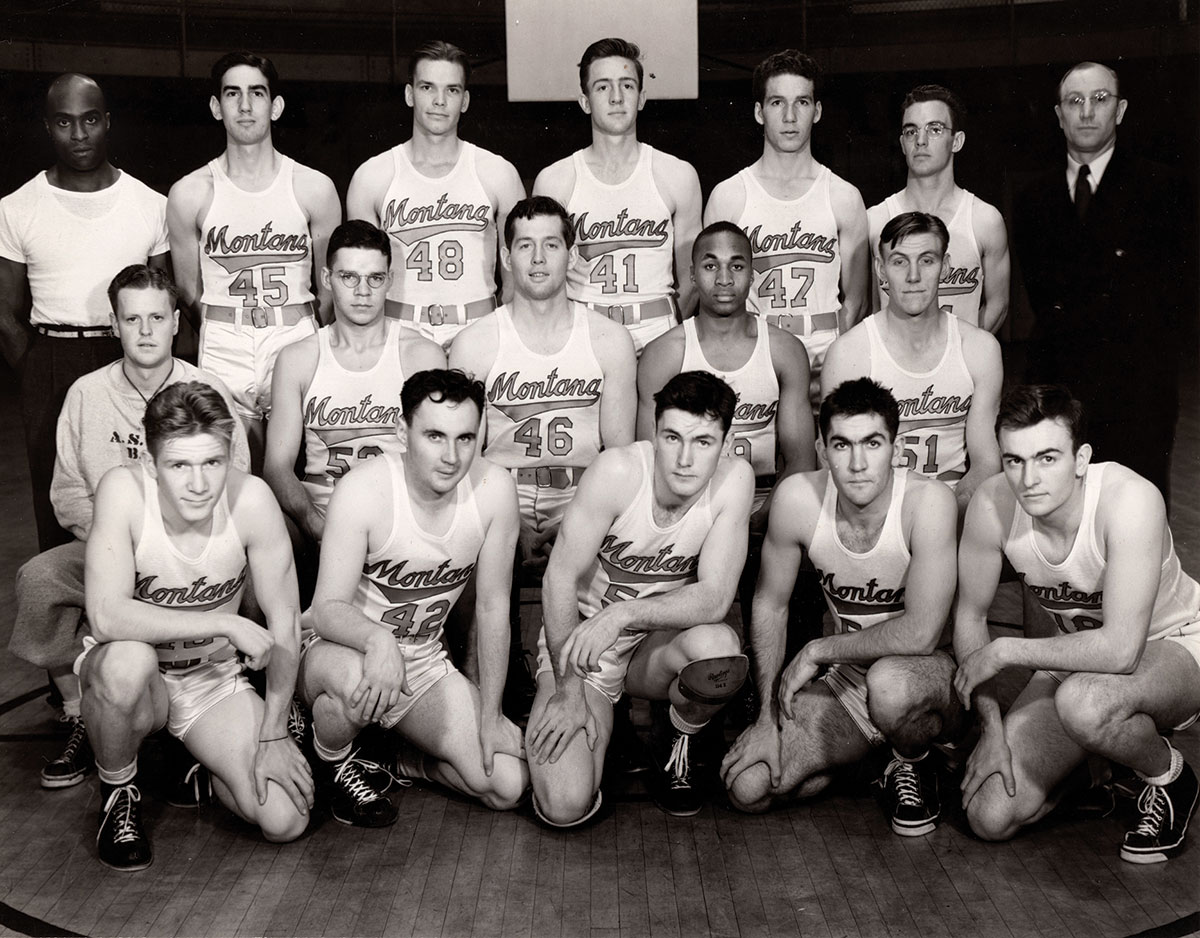

A starting guard when he played for the Montana Grizzlies, Burgess later joined a team of medical students at Duke University who matched up against a local college squad with a record of 19-1 that happened to be black. He was a catalyst for this breakthrough game, which was played in a closed, empty gym in Durham, N.C., on March 19, 1944. It was, almost without question, the first time an organized game pitted an all-white team against one that was all black. And it happened in the segregated South.

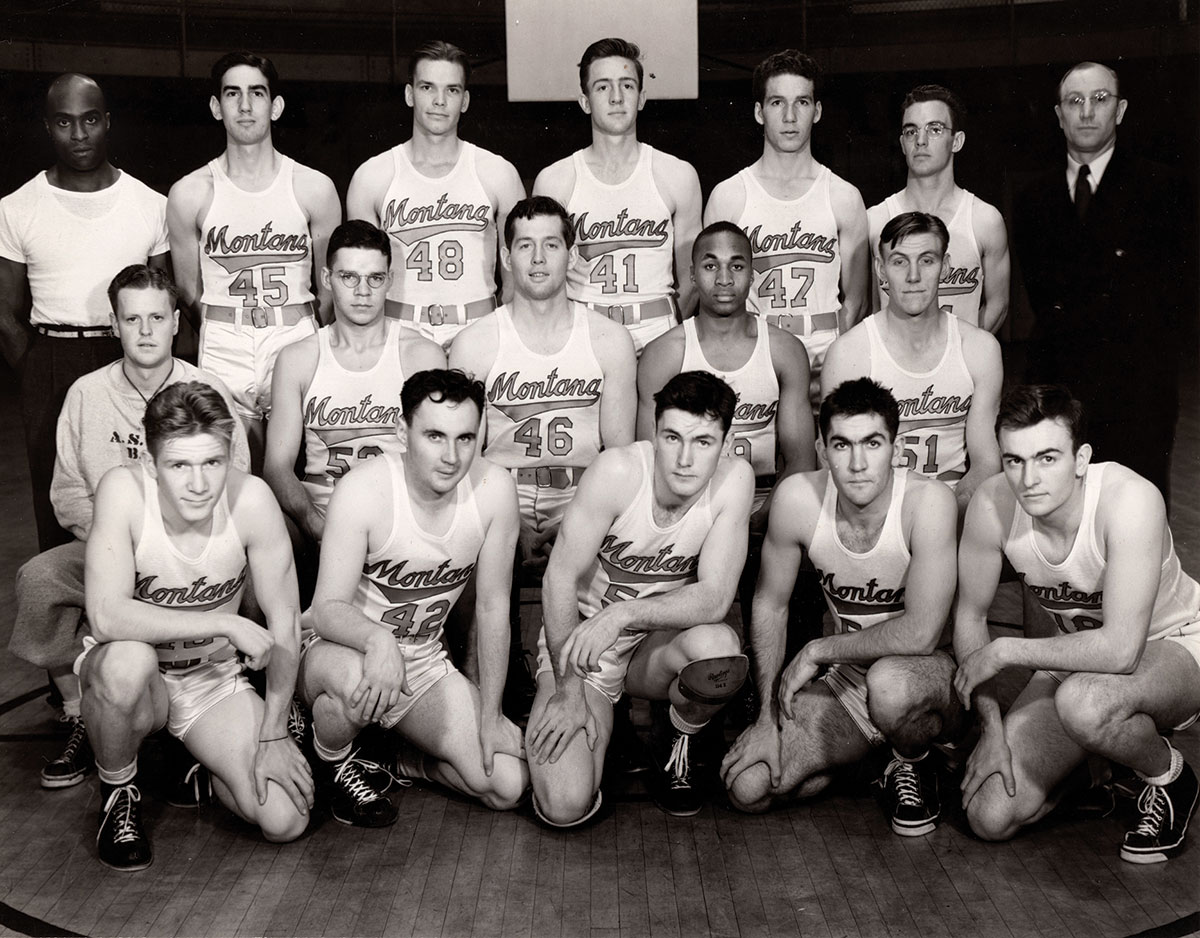

Born in the Fort Peck Indian Reservation town of Wolf Point, Burgess had an approach to race relations that was progressive for the 1940s. He grew up around Native Americans, and he roomed with Joe Taylor, a black teammate at UM, on road trips.

Burgess and Taylor were part of Grizzly teams that went 14-10 under legendary UM coach George “Jiggs” Dahlberg and 15-9 under Clyde Carpenter and Ed Chinske. Meanwhile, World War II was heating up, and the teammates got a sobering taste of segregation when the entire Montana basketball team enlisted after the 1942-43 season. Taylor went into a black unit.

“That was the last I saw of Joe,” Burgess says in a 1997 interview with ABC’s Nightline. “He went one way, and I went the other.”

Dare to Play

“The Indian kids taught me to play basketball,” Burgess once said, and he grew up to be around 6-foot-1—an athletic kid who became a solid passer and excellent defender at UM. When the team enlisted, Burgess joined the Army, but at the behest of a Placid Lake neighbor, he also applied to the Duke University School of Medicine. The implication is that for Burgess, the son of a dentist, strings were pulled.

Not long after arriving in Durham, he joined Duke’s medical school team—a strong squad full of college basketball players—which was up for any challenge. And when the challenge was issued to play the North Carolina College for Negroes at the local YMCA, Burgess was all for it.

Some of his teammates, however, grew up in the South and were not.

Disobeying the Jim Crow laws of the region was no simple act of disobedience, and Burgess himself had a bus driver pull a knife on him when he opposed, out loud, the “back-of-the-bus” seating arrangements.

So Burgess played pivot in getting his teammates on board for the game, speaking to each player in turn and then, as a last resort, flat-out asking them if they were scared.

The game was scheduled for a Sunday morning, when most of Durham would be in church. The Duke med students traveled to the black college by the back roads and entered the gym with coats over their heads.

The game was a runaway: The NCCN Eagles, playing a fast-break style championed by Hall of Fame coach John McClendon, found their stride after a slow start and won 88-44.

Then the teams kept playing, mixing players for a game of shirts and skins.

This seems prosaic these days to anyone who has worked up a sweat at the Rec Center at UM or at the YMCA in Billings. Maybe that is why, before author Scott Ellsworth sniffed out the origins of the game in 1996, none of Burgess’ four children knew of it.

Perhaps therein lies the beauty. It was such a natural thing to do, Burgess gave it no second thought.

Coach McClendon did.

“I don’t remember ever shaking hands with a white man before that,” he says.

Scott Ellsworth’s The Secret Game [$27, Little, Brown and Company] has been called one of the top ten books of 2015 by The Chicago Tribune, was added to the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing long list, and was named one of six “Sports Books of the Year” by Sports Illustrated. The book also is available in audio and e-book editions. Ellsworth teaches at the University of Michigan and has written about history for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times.

The Patriarch

“He was a friend to the world, setting an example I find hard to live up to,” Burgess’ son Kelly says, noting one occasion at the cabin when some Amish families appeared, having traversed the Jocko Pass from the Mission Valley via horse and wagon.

“He ran up the road and invited them to stop and visit, corral and water their horses, and use our dock to swim,” Kelly says.

Burgess met his wife, Donna, at UM in 1947 while home on break. She was dating a friend of his, but that didn’t stop him from taking her on a picnic and then to a dance.

“Three weeks later we were engaged,” she says. They married in Butte in 1948, and she traveled with him back to Duke, where he finished his internship, and then to Kentucky, where he did his residency.

From there, Burgess served his country in the Korean War as an evac doctor and then as director of hospital trains.

“He was at the peace accord at Panmunjom when the treaty was signed,” Donna notes. “Which is still in force, I believe.”

Donna lives in an apartment not far off Last Chance Gulch in Helena. The entryway wall is covered in pictures that paint Burgess as traveler of Forrest Gump proportions: Here he is with Mike Mansfield, years after he took one of Mansfield’s classes as UM; over here is Jacques Cousteau, whom the Burgesses met by chance on a trip to Alaska.

He didn’t know Richard Hooker, the Korean War surgeon who co-wrote the screenplay for M*A*S*H, but Burgess was reasonably sure a buddy of his who organized a polo game involving Jeeps was the model for the character “Hawkeye.”

Burgess was a hard-working man: Out the door at 6 a.m., with a stop at the Peter Pan restaurant in Helena—“Then the 4Bs after the Peter Pan closed,” Donna says. Then he’d make rounds at the hospital, then tackle his surgical schedule, then more rounds, then house calls. He’d come home between seven and eight, having skipped lunch.

“I always cooked two dinners,” Donna says.

They raised their four kids and traveled, with both Jack and Donna holding pilot licenses. This was more practical than you’d think. His daughter Sidney recalled taking off from Helena toward Portland, Ore., to see some colleges. Once at cruising altitude, her father said, “See that notch in the clouds? Keep us pointed at that,” and took a nap.

His affinity to sleep as soon as he sat down caused his kids to sing I’m Henry the VIII, I Am on car rides and gave Donna plenty of time on the airplane stick.

“I might have had more flight hours than he did,” she says.

Southern Discomfort

The Secret Game and many of the factors that led up to it are explored in Ellsworth’s book by the same title. In 317 pages, Ellsworth writes about the racial attitudes of the day, and, chillingly, of the shooting of an Army private, Booker Spicely, for not moving to the back of a Durham bus in 1944.

An all-white jury deliberated for just twenty-eight minutes before acquitting bus driver Lee Council of murder.

Against this backdrop, how was anyone to push back against Jim Crow? At the Duke University Hospital, Burgess had his own sobering experience.

As a first-year medical student, he took turns with other interns presenting patients to a professor. When Burgess’ turn came, he began by addressing the black patient, “Good morning, Mrs. Smith,” and then completed his examination. When the students reached the hallway, the professor and a few students turned on him.

“Don’t ever call a n---- Mr. or Mrs., you hear?” he was told.

This memory was jarred loose by Ellsworth, who tracked down another med school student, David Hubbell, by cross-referencing a box score in the Durham newspaper with a list of Duke med school graduates. By then, Hubbell, who’d played basketball at Duke and earned his undergraduate degree in 1943, was a surgeon in Florida. That eventually led to Burgess, who during his time away from home had written more than 200 letters to his parents. In one of them he mentioned the game, which helped Ellsworth nail down a date for a contest that wasn’t reported in the papers of the day.

More than fifty years later, Nightline devoted its April 1, 1997, broadcast to the contest.

“They built up a big lead on us,” says Ed Boyd, one of the NCCN Eagles. “Until we found out that nobody was going to get hurt, and the black wouldn’t rub off and the white wouldn’t rub off. And that’s when we went to work.”

It’s hard to quantify the game’s impact in the immediate aftermath, but it appears word got out to the right people. Ellsworth notes that the Cloudbusters, a Navy flight-school team stationed in Chapel Hill, N.C., started a caravan of all-white teams that quietly traveled to NCCN looking for games.

It meant a lot to those involved, and Boyd expressed his appreciation.

“For the sake of a game, and for the sake of their love of the game, they took a great chance,” he says of the Duke medical students. “And we’ve all benefited from it.”

In 1948 the Indiana State Teachers College, led by legendary coach John Wooden and now called Indiana State University, for the first time took a black player to the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball Tournament. Two years later, the NCAA and NIT tournaments included integrated teams.

By then Burgess was in Lexington, Ky., completing his residency. Western Kentucky University, about two and a half hours from Lexington, would eventually integrate college basketball in the region with the addition of two black players in 1963.

Final Flights

Burgess was a Helena institution by then, an avid skier, fisherman, pilot, and Santa Claus.

In 1964, he and Donna organized a European charter for fellow skiers and other friends. A DC-7 took off from Helena and headed to Montreal, then Shannon, Ireland, and then to Munich.

In 1965, eight-year-old Eileen figured out that Santa Claus was, in fact, her dad. He’d had a velvet suit sent to him by his sisters, and for years he arranged with Helena families to leave their presents, labeled, outside on the porch. Then Santa would knock on the door and bring them in every Christmas Eve.

“The ultimate measure of a man,” Martin Luther King Jr. said, “is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

Burgess stood tall, in a near-empty gym in Durham, N.C., and at a clinic for the underprivileged in Helena. His father had died of a heart attack on a Missoula golf course in his early fifties, so he figured his time might be fairly short.

“When I have my big one, you’ll have to take over doing this,” he told Kelly, while priming the pumps at the cabin. His handwritten directions for priming and draining the pipes are still on the wall.

Burgess made it to eighty before heart problems made a valve-transplant necessary. It didn’t take; he passed away ten days after the operation, on July 19, 2003, at the apartment in Helena.

It was the heart of summer, and it’s easy to imagine he wished he was at Placid Lake, where the cabin shutter is covered by a crewel tapestry depicting the two fair seasons.

On the far right panel is a plane, banking over a dock on which a child sits, letting the family know their patriarch is coming home one last time.