- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

UM takes innovative approaches to prepare the teachers of tomorrow

Early in her teaching career, Roberta Evans coached high school speech and debate at Robert McQueen High School in Reno, Nevada, where she met a senior with exceptional talent for humorous interpretation.

Early in her teaching career, Roberta Evans coached high school speech and debate at Robert McQueen High School in Reno, Nevada, where she met a senior with exceptional talent for humorous interpretation.

“But he was a walking disaster,” says Evans, now dean of the Phyllis J. Washington College of Education & Human Sciences at the University of Montana. “He had papers jammed into a folder, and he appeared to me to be disorganized. I warned him that until that material is typed and presented in a folio, he was not boarding the bus to compete.”

As the team prepared to leave for the next meet, she noticed the boy was missing and asked his best friend where he was.

“He won’t want me to tell you this,” the friend told her, “but he’s living in a car with his uncle under the Wells Avenue overpass.”

“And that,” says Evans, “was a powerful epiphany regarding the true meaning of being a teacher. I realized the 10 billion biases I brought to work with me every single day.”

The lesson Evans learned that day is one she has carried with her to UM: Being a teacher is not just about pushing kids to meet standards, it’s about understanding how to empower individuals – all of whom are navigating the world in vastly different ways.

That view is essential to the college, but particularly vital for UM students pursuing careers in teaching prekindergarten through 12th grade. The profession has faced complicated issues, especially in the past decade. Teacher shortages due to low pay and poor working conditions, Evans says, are compounded by the failures of national reforms, with their narrow focus on testing mandates, and budget cuts in the arts, social studies, science and physical education.

Meanwhile, a grim and false national narrative ignores tremendously successful projects and partnerships happening in schools everywhere, especially Montana.

“The national narrative surrounding teachers has not been good for a long time,” says Adrea Lawrence, an associate professor and chair of UM’s Department of Teaching and Learning. “It’s done as much as anything to undermine the profession. But when I talk to my students and get to hear about their clinical work in different schools, it’s thrilling.”

UM’s clinical component allows students to spend more time in classrooms than many other education programs. In fact, Lawrence says, UM’s offerings for pre-K-12 education are much broader than a year ago, and include a new gifted program, robotics, an expansion of the International Baccalaureate program, and grant-funded projects in STEM and the arts, among other new certifications.

It’s clear the leaders of UM’s education program are part of a national movement to strengthen curriculum and provide students with the best training to teach.

“I’m fortunate to work with passionate and brilliant people, and our students are outstanding,” Evans says. “The vision here is created by fabulous superstars in every content area across the college.”

The partnerships with UM and Missoula schools and the cutting-edge work done by professors are leading the way in preparing students not just to face the future, but to shape it in the best ways possible.

When Martin Horejsi first started teaching at UM in 2007, wireless technology on campus was thin. The Montana Digital Academy was just transitioning to a full-on virtual classroom, and professors experimented with online teaching programs. During the next few years, however, as social media and smartphone use exploded, new students arrived with increasing experience and expectations. UM needed to keep pace.

For Horejsi, who specializes in technology and education, it is an interesting problem to solve, one that extends beyond campus and into classrooms everywhere. How do you transform the layout using the latest technological tools? How do you take the technology students already use and efficiently incorporate it into their education?

“We’re trying to figure out how to maximize the potential of these powerful tools and still address new questions about security, privacy and compliance with federal regulations,” Horejsi says.

An associate professor in the Department of Teaching and Learning, Horejsi teaches technology courses and instructional design. He talks about the future of education with great excitement. The possibilities of interconnecting devices, for instance, could change how students collect data in a science lab.

One of Horesji’s students is working with Missoula’s Hellgate Elementary on an iPad project. Initially, the school had turned off Siri, the digital assistant, so it wouldn’t distract students. As part of the project, Siri was switched back on to study the ways in which information at their fingertips could, in fact, streamline learning.

“If I’m working on a science project and I need to add up a column of numbers, I could say, ‘Hey, Siri, what is 10 plus 3 plus 9 plus 14 plus 82 plus 64, all divided by 3? And, boom!” Horejsi says. “It tells me. What you wind up with is a much greater flow, the ability to have the students stay on the primary task. This isn’t math class. They just need the answer to move forward.”

Horejsi has seen the way digital technology in education failed early on, particularly when teachers tried to create digital classrooms with the same principles as face-to-face spaces.

“When you do that, you lose what digital does best and maximize what it does worst,” he says.

His goal is to teach his students to be teachers who understand the latest technology and can be innovative with it, but at the same time be critical and understand when it’s appropriate to use.

“Sometimes a pen and the back of an envelope are all you need to come up with an idea,” Horejsi says. “And when that’s no longer effective, you transition to another tool. Our students should come to the classroom fairly clear on that distinction, but also arrive with a powerful set of skills that gives them teaching superpowers to challenge themselves and empower their students.”

Scientists have learned a great deal about early childhood development from a study done in Romania after an 1989 overthrow of the country’s repressive regime. At that point, almost 170,000 orphans languished in institutions, suffering mostly from lack of adult interaction and affection.

A recent analysis of the 13-year study gives programs like UM’s Early Childhood Education newfound urgency.

“Those of us in the field have always realized and believed that the early years are extremely, extremely important,” says Julie Bullard, a professor in UM’s Department of Teaching and Learning. “But I think more recently the rest of the world is catching up in that belief.”

UM offers an undergraduate major, minor and two online master’s programs in early childhood education, which spans birth to age 8. In one master’s class, students create “semi-extreme” makeovers of their classrooms and are taught to treat their spaces with a social anthropologist’s eye. They observe how it functions and pinpoint what teachers and children value before planning the classroom.

One of Bullard’s students, for example, used her coursework to design and open a brand-new early childhood facility in Missoula.

“In early education we’re thinking of the whole child – social, emotional, physical, as well as academic,” Bullard says. “So we want them to be in wonderful environments where they will get everything they need to develop to their full capacity.”

In a brainstorming session, Bullard and her colleagues came up with the idea of having student-teachers wear GoPro cameras to document their progress, with the lens turned toward the kids in the classroom. In November, Bullard presented the idea at a national education conference in Los Angeles, and she and colleague Kate Brayko plan to write an article about the approach.

“We really value the teacher facilitating learning and not being the sage on the stage,” Bullard says. “With the GoPro, the focus is on the learner rather than the teacher. The students can review the clips and see how the kids responded. It’s a great self-reflection tool.”

Students in early childhood education are taught to address real problems in the classroom, but the issues are much bigger. Studies show that infants and toddlers do best with caregivers who have a degree in the field, but wages are so low that qualified workers are difficult to retain.

“It’s becoming a crisis, and people end up leaving their children in situations they don’t feel good about,” Bullard says.

Some state-level efforts are in the works to address this issue, and UM leads the charge. This semester, for instance, students in the advanced early childhood master’s program can take a class on public policy and advocacy.

“I’m really excited to see what kind of projects come out of that,” Bullard says. “It seems perfectly timed with the Legislature in session. One of the goals is that students come out of the program as advocates for early childhood education in the state and in the nation.”

At Frenchtown Elementary, Brandon Wood is teaching his third-graders to make laptops out of pizza boxes. Not functional laptops, of course, but pretty believable replicas with a motherboard, battery, fan, keyboard and cords.

“That’s been something the kids have been really excited about and taken to the next level,” he says. “They can open it up and show their parents what’s inside.”

Wood is a graduate of UM’s education program, where he learned about teaching robotics in a science methods course taught by Professor Lisa Blank. At Frenchtown, he started a robotics program with a team from the school’s gifted and talented program, but the enthusiasm from all students encouraged him to form one specifically for girls and yet another in the after-school program.

All three are competing in this year’s First Lego League, a competition that includes a robot mission and research project.

All three are competing in this year’s First Lego League, a competition that includes a robot mission and research project.

“One team is working on how to alleviate pet boredom when you leave them for the day,” Wood says. “Another team is trying to alleviate animal crossing accidents.”

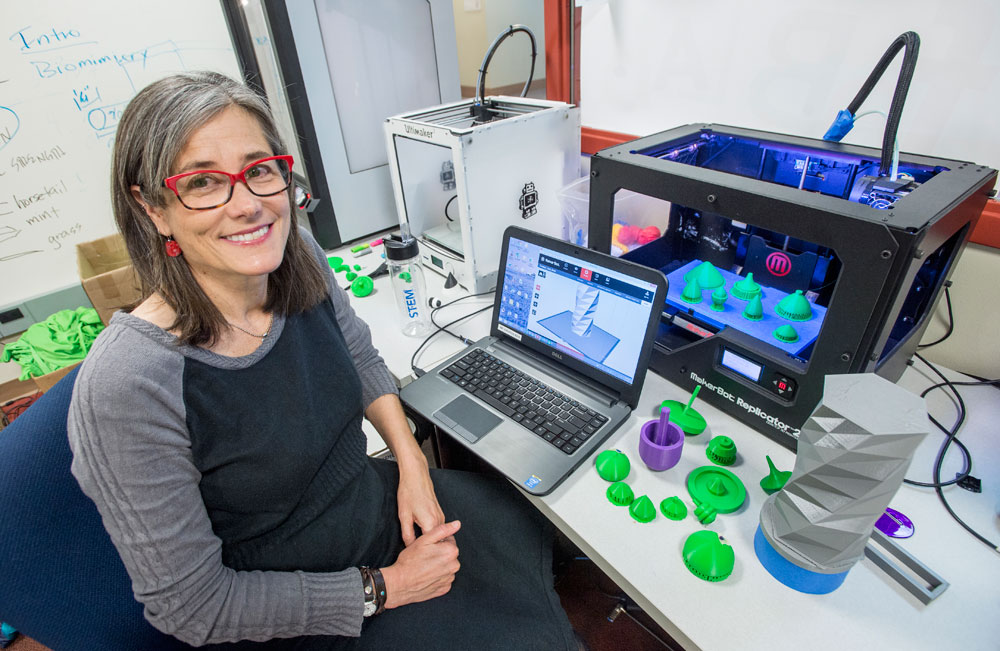

Robotics and computational thinking are highly valued skills in today’s job market. At UM, Blank is pushing to make computational thinking and associated skills – coding and programming – a central component for UM students looking to teach in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields. Currently, she collaborates with colleagues David Erickson, Yolanda Reimer and Tom Gallagher to offer a computer science teaching endorsement, which alleviates bottleneck issues such as a lack of teachers trained in programming.

To further help, Reimer and Blank recently received a National Science Foundation grant to develop a programming curriculum aimed at high schoolers. Blank also secured UM as the “Project Lead the Way” affiliate for Montana, which provides K-12 STEM curriculum pathways in computer science, engineering and biomedical science.

Another big push in STEM education is engaging young girls who often are implicitly and explicitly discouraged from science and math. In response to that longtime trend, Blank and UM colleagues Martha Robertson and Jessie Herbert implemented a middle school STEM career conference with the help of Washington Foundation funding.

“One of the goals with the conference is to bring in female role models because they make a significant difference in whether girls persist in STEM careers,” Blank says.

Similarly, STEM careers haven’t always been accessible to tribal communities. With NSF funding, Blank is working with spectrUM Discovery Area and SciNation to help build a mobile makerspace – an area for technological creation and tinkering – on the Flathead Indian Reservation, which will stay with the community after the grant expires. The makerspace will incorporate design thinking, spatial visualization, material science, laser cutting and 3-D printing, among other technology.

UM’s partnership with public schools and commitment to fostering STEM-capable teachers like Brandon Wood mean Montana students won’t be left behind, no matter what the future brings.

“I tell the kids at some point they’re going to be old enough to make educated decisions on this,” Wood says. “Even if they don’t go into robotics, they’ll have to vote on these things and think ethically and deeply about what we’re doing with these robots.”

Universal Design often is associated with architecture – a set of principles, such as flatter surfaces or wider doorways – that make a landscape accessible to everyone. In the classroom, Universal Design Learning refers to teaching approaches that consider the individual and create an inclusive environment for everyone. Scott Hohnstein, an instructor in the Department of Teaching and Learning, teaches courses on exceptionalities and classroom management using UDL. Exceptionalities refer to the diverse array of abilities in the classroom. The largest group in this category is those with learning disabilities, but the term also covers gifted learners.

In the past, special education, like accessibility design for buildings, has been used as an approach because the “normal” or traditional ways don’t work. But with UDL, Hohnstein and his colleagues try to upend that misconception.

“I think of exceptionalities as an inclusive definition and not so much special education versus general education,” Hohnstein says. “How can ideas in special education inform education, in general, and how can we look at it more holistically and create an all-encompassing classroom?”

At the core of Hohnstein’s exceptionalities class is the investigation into why there is such a disproportionate number of students from ethnic minority groups placed in special education. His background working with diverse populations in Columbus, Ohio, and Taiwan opened his eyes to some of the prejudices people, and often teachers, bring to the table.

“In my classes, I’m trying to take a multicultural educational approach and encourage students to constantly think about how they can expand their sociocultural awareness, and in doing so, be very aware of our prejudicial thinking,” he says.

Hohnstein debunks the outdated theories that genetics or cultural inferiority are the driving forces behind the makeup of special education classrooms. Instead, he teaches them to consider factors of poverty and oppression, as well as cultural diversity. He teaches his students to represent information and engage their own class in multiple ways and create multiple means of expression by thinking about kids’ varying backgrounds.

“A student wouldn’t just have to write a paper,” Hohnstein says. “They might create a comic strip or a poem or a rap. It’s a way of differentiating the instruction.”

Like other teachers in the education college, Hohnstein embraces how technology can help further Universal Design Learning. That includes in his own classroom where, along with face-to-face learners, a few students from Flathead Valley and Blackfeet community colleges take his course via iPad robots. Distance is inevitable, Hohnstein says, whether it’s physical or in the way we learn.

“We can still maintain that core of what I think teaching has always been, which is creating a connection,” he says. “I believe that’s at the core of learning – it’s you helping me and me helping you.”