- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

"When I look back on it, the thing that sticks out in my mind about the University was the incredible international flavor on campus. I had opportunities to hear from people from all around our globe about their perspectives, their lives and their experiences. I got a very culturally enriching experience, and I stayed right in Montana to do it.”

Kelly Elder

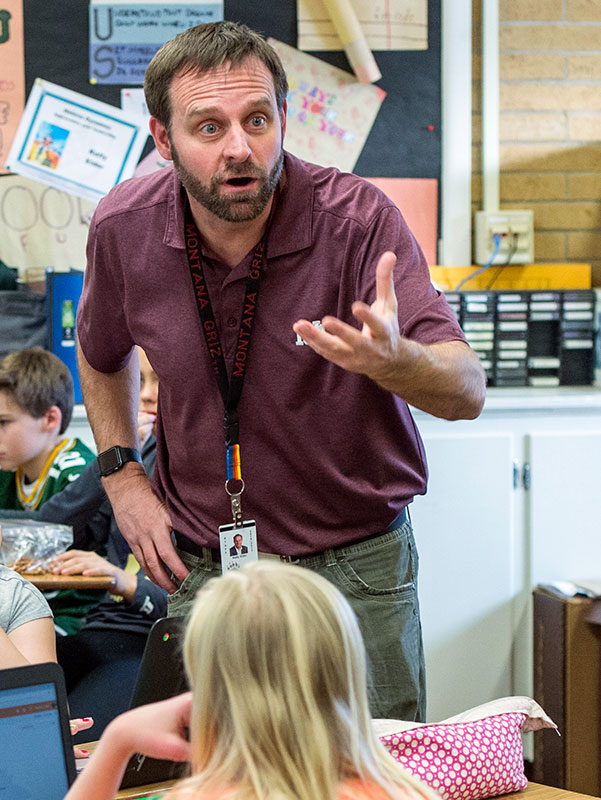

Kelly Elder doesn’t remember a single one of his middle school teachers.

That’s significant, because Elder can give a fairly photographic recounting of the other educators who influenced his life – and there are many – from elementary school through his graduate studies at the University of Montana. It’s also ironic, since the 2017 Montana Teacher of the Year currently teaches sixth-grade social studies at C.R. Anderson Middle School in Helena.

Like Elder (and the rest of us) at that age, the students in his classroom are experiencing such rapid physical and emotional growth that the journey from childhood to adolescence may ultimately crowd everything else out of their memories. On the other hand, Elder says, that extraordinary development is one reason the middle school years are so vital for young learners.

“I try every day to give it my best, but chances are quite good they’re going to remember little or nothing about this part of their educational lives,” he says, a rueful humor in his voice. “At the same time, there is no better time to give these students a good foundation for academic success. If we can help instill in them confidence, independence, organization and work ethic, those skills are just critically important.”

Despite its challenges, Elder is perfectly suited to teach this age group. There’s an easy warmth to him, a natural enthusiasm for whatever he’s discussing that he balances with a genuine interest in whatever the other person has to say. It’s plain to see how kids of any age would gravitate to him and consider him an adult they trust.

Elder came to C.R. Anderson after spending nearly a decade teaching high school in Lewistown, Montana. The much smaller Fergus High was a great situation for him, Elder says – a terrific institution backed by a supportive, involved community – but as he got older, the five-hour drive separating him from family and friends in Helena started to be too much. Ultimately, the decision to trade high school for middle school was about being closer to his childhood home.

Elder’s family had moved from California to Montana’s capital city in 1976, when he was in second grade. He went on to graduate from Capital High School and then earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s in political science, both from UM.

At first, Elder says he planned to use his college years to travel. He thought he would spend a year or two in Missoula and then sign up for a national student exchange program, transfer to some faraway locale and ultimately graduate from an out-of-state school. However, after spending some time at UM, he discovered he didn’t need to do that.

“I was a Montana student who really wanted to get out and see the world,” he says, “but when I look back on it, the thing that sticks out in my mind about the University was the incredible international flavor on campus. I had opportunities to hear from people from all around our globe about their perspectives, their lives and their experiences. I got a very culturally enriching experience, and I stayed right in Montana to do it.”

In what would become a blueprint for the rest of his life, Elder got heavily involved at UM. He spent time as a resident assistant in the dorms and volunteered for the UM Advocates program in a number of capacities: working in the president’s office, for alumni relations and with new student services.

For graduate school he was awarded a James Madison Fellowship, which required him to complete his final six credits at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., but otherwise allowed him to attend any university in the country free of charge. In a telling move, Elder chose UM.

It was while working as an Advocate that he says he discovered his love for teaching. He’d always been a social person and now decided to translate those skills into trying to help others.

These days, Elder’s résumé and schedule remain fairly dizzying. He is one of just 90 National Board Certified Teachers in Montana, and he’s also serving as the state’s Teacher of the Year.

In addition to his full-time duties in the classroom, he’s the leader of C.R. Anderson’s mountain biking club and is the associate director for the Montana Association of Student Councils. He also directed a student group running a holiday toy drive for Toys for Tots, a fundraiser for the Montana Make-A-Wish Foundation, and a push to help students facing intense challenges during the holiday season.

It all adds up to a busy schedule that Elder admits sometimes leaves little time for anything else. Still, he contends he can unplug and find time away when he needs to recharge. As for hobbies, as if he needs them, he dabbles in photography and is learning Spanish.

“I have so many friends that, when they leave their jobs for the night, they’re done,” he says, “but when you’re a teacher it’s far more complicated than that. There is no start time and no end time, but I think the intrinsic rewards more than make up for that.”

In the summer, Elder works for the U.S. Forest Service on the Helena National Forest. He began his career there while he was in college, working as a firefighter on a hotshot crew. In the past few years, he’s moved off the fire line and begun work as an aircraft dispatcher, controlling the comings and goings of fixed- and rotor-winged aircraft in the backcountry during fire season.

Perhaps the extracurricular activity that is closest to Elder’s heart, however, is organizing trips for the students at C.R. Anderson. In the past, he’s chaperoned students to places like Costa Rica, Guatemala, Japan, and Washington, D.C. They’ve snorkeled in “shark alley,” gotten up close and personal with monkeys, spiders and snakes in the rainforest, and attended the inauguration of a new American president. In April, Elder will lead a group of kids on their next expedition to Belize.

With these trips, Elder gives a new generation of students the opportunity he once craved as a younger person. He provides the chance to get out and see the world – to experience life and culture outside the borders of their home state and sometimes on the opposite side of the ocean.

“What’s beautiful is when you can inspire students to push out of their comfort zones and try something new,” Elder explains. “There’s nothing better. When you see that success, wow, it’s so fun. At the sixth-grade level I’ve got all these eager young people, and my job is to share with these Montana kids – heck, I’m a Montana kid – and get them excited to learn about other parts of the world and to see what’s out there.”

If he’s lucky, perhaps one of those trips will give his students an experience they might, just maybe, remember for the rest of their lives.

"I just feel like the best part about working with young people is getting to know them and watching them grow. I often say these are great kids, and they’re going to be great adults. I can’t wait to talk to them when they’re 23 or 25 or 30.”

Anna Baldwin

“I don’t have, like, a great story,” says Anna Baldwin, as she begins explaining how a kid who grew up in Virginia never wanting to be a teacher became one of the most accomplished and influential educators in Montana.

Of course, she’s just being humble. The story of Baldwin’s career so far is actually pretty remarkable – doubly so, since it feels like she’s just getting started.

As she tells her “not-great story,” Baldwin is sitting in her classroom at Arlee High School, 30 miles north of Missoula on the Flathead Indian Reservation. She has taught English and history here for the past 14 years, and the room’s eclectic décor speaks to that journey.

Album covers from her own collection line the walls near the ceiling: Prince, Guns n’ Roses, The Clash, Violent Femmes. The flag of the Flathead Nation hangs in one corner. There are posters of Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela and quotes from Socrates and Mahatma Gandhi. There also is one attributed to The Borg – the cyborg villains from “Star Trek: The Next Generation” – and a picture of Jedi Grandmaster Yoda with a caption that reads: “Metaphors be with you.”

Across the table from Baldwin, on a shelf next to her desk, is a framed photograph of her with former President Barack Obama. The picture was taken at the White House in May 2014, after Baldwin was named Montana Teacher of the Year.

So, not a great story?

Yeah, right.

Teacher of the Year is the highest honor available to educators in Montana public schools. The application process is notoriously exhaustive but also rewarding – forcing teachers to evaluate everything from overall teaching methods to individual lesson plans. The Montana Professional Teaching Association says the eventual winner “personifies the best in the teaching profession … serve[s] as an ambassador for public education, and attend[s] numerous national events along with the other state teachers of the year.”

They also get to meet the president.

“Going to the White House was probably one of the most exciting moments of my life,” Baldwin says, “but in the larger scope of what we were doing that year, it was just one snippet of a much larger experience. I was thrust into a position where I had to really know myself and what I stood for as a teacher.”

Before coming to Arlee, Baldwin spent four years teaching a bit farther north on Highway 93 at Two Eagle River School, the tribal alternative high school in Pablo. She also has taught English in Nicaragua and the Pacific Islands and as an adjunct at UM.

In 2011, she was recognized as the Arlee School Staff Member of the Year and won the Distinguished Educator Award from the Montana Association of Teachers of English Language Arts. In 2012, she earned national recognition from the Southern Poverty Law Center for Excellence in Culturally Responsive Teaching.

Now, in addition to her full-time schedule in Arlee, she teaches an online Native American studies class she designed for the Montana Digital Academy. She’s also a Teaching Ambassador Fellow for the Department of Education, acting as a liaison between policymakers in Washington, D.C., and teachers on the ground to ensure everyone stays up to date on education policies and their ramifications.

A week before she sits down to tell her own story, Baldwin facilitated a roundtable in Polson for teachers and administrators from four Montana reservation districts. The next day, she flew to San Jose, California, to accompany Secretary of Education John King on some school visits she organized.

“Honestly, it kind of never stops,” says Jerry Baldwin, Anna’s husband, a ceramic artist who studied fine art at UM. “She’ll come home and we’ll have dinner, and the next thing you know it’ll be 10 o’clock and she’s still working and hasn’t even changed out of her work clothes. Next thing, I’ll find her asleep in a chair in front of her laptop.”

Anna Baldwin admits it’s all made for a busy and different life than she once imagined for herself. Early on she had no interest in teaching.

“I can remember distinctly in high school sitting in back of the room, listening to my classmates say really mean and rude things about the teacher,” she says. “I thought, ‘I would never be a teacher, that sounds awful.’”

She started to change her mind while working toward an undergraduate degree in English literature at Georgetown University. For three years she volunteered with the D.C. Schools Project, serving as a tutor in an English-as-a-second-language classroom at Bell Multicultural High School. Baldwin enjoyed it so much she began to consider teaching as a career.

After moving west in 1995, she earned a pair of UM graduate degrees – a master’s in English teaching and a doctorate of education in curriculum and instruction. Now she lives within walking distance from Arlee High, where total enrollment is around 130 students and the student body is 70 percent Native American.

On this day, Baldwin leads a dozen students in a lesson about Harper Lee’s iconic novel “To Kill a Mockingbird.” The students sit in groups of three or four at circular tables, with their matching, school-issued laptops open in front of them.

Baldwin is energetic and friendly, accessible to the students but also a taskmaster, cruising around the room in a pair of red leopard-print clogs. Near the end of the period, each group presents a short skit from a scene in the book.

They stand in front of a makeshift green screen made from several enormous pieces of paper taped to the wall. Baldwin films them with her iPad, using an app that allows her to superimpose the students on digital backgrounds – a schoolroom and a house that both look like they’ve been plucked out of the South during the Great Depression. In this way, she is literally able to put the students in the book they are reading.

It’s a good lesson. It gets the kids out of their seats and forces them to engage with Lee’s writing in a way they might not get from their own reading. It’s fun and has just enough technological bells and whistles to keep a room full of teenagers focused on the task at hand.

“She’s a really good teacher,” says Tyler Adams, a senior wearing western jeans and a saucer-sized belt buckle proclaiming him a high school rodeo champion. “She really knows what she’s talking about. She’s really helpful.”

Adams says he’ll graduate early this year and will enroll at Missoula College, where he’ll study heavy machinery. Despite the fact Baldwin may not think her journey from Virginia to Montana makes for a great story, he and the rest of her students seem pretty glad it ended with her here.

While unexpected, Baldwin seems happy with that outcome, too.

“I just feel like the best part about working with young people is getting to know them and watching them grow,” she says. “I often say these are great kids, and they’re going to be great adults. I can’t wait to talk to them when they’re 23 or 25 or 30.”

"It wasn’t just about acting, it was about becoming a better person and getting to the depth of the material you were working with. I learned how art is influenced by culture and society and the responsibility we have as artists. The experience (at UM) was without peer.”

Art Almquist

When Art Almquist arrived at Tucson Magnet High School during the fall of 1996, the theater program was in dire need of resurrection.

Almquist had been contacted about the school’s opening for a drama teacher the previous semester, while he was still in Missoula finishing up graduate school at UM. It took several months before he could officially accept the position and make the 1,300-mile move south.

When he got there, he discovered the department he was about to take over had fallen on hard times.

“The program was really in disarray,” Almquist says. “The theater was a mess. The curtains were torn. There was no technical booth. So I just went into fundraising overdrive – and the more people started hearing about the program, the more kids started coming.”

Fast-forward two decades and Almquist’s drama program at Tucson Magnet is one of the premier high school theater troupes in Arizona, if not the nation. His stage productions are regarded among the crown jewels of Tucson’s huge public arts and sciences high school, which boasts a 32-acre campus and enrollment of around 3,300.

Almquist now is one of three drama teachers in the thriving program. He estimates around 130 students each year take his beginning acting classes. Of those, roughly 80 continue on into intermediate drama, and by the time they are upperclassmen, 40 to 50 take part in the advanced-level acting, film acting and musical theater classes.

At the moment, the school just wrapped its fall production of “Too Fast,” a play by contemporary Scottish playwright Douglas Maxwell. Like most of Almquist’s productions, it played to packed houses. Almquist says it’s not unusual for people to come from all over the state to attend, gladly paying the $10 admission fee because they know the quality will be on par with a professional production they might pay five times as much to see.

The program’s stunning success has brought Almquist national recognition. In 2013, he was named People Magazine’s Readers’ Choice Teacher of the Year after winning a nationwide online vote in a landslide. This year, he also garnered the Reba R. Robertson Award, an honor given annually by the

Children’s Theater Foundation of America to one of the nation’s top high school drama teachers.

So, what’s his secret?

“The biggest thing is getting the kids to believe in themselves,” Almquist says. “That sounds a little cheesy, but it really is about that. To get up on stage and create anything that has any meaning you have to be willing to be vulnerable. You have to be willing to take that risk.”

Much of the work still draws on the fundamentals Almquist learned while earning an M.F.A. in acting and an M.A. in performance theory and criticism at UM. He came to Montana in 1992 after studying theater, education and English at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, and spending a few years teaching at a small boarding school in Connecticut.

As an Arizona native, Almquist says he fell in love with Missoula and the UM theater program after visiting the campus. As a student, he learned the building blocks of storytelling and honed his craft as an actor, improv comedian and director.

“The quality of the education was just fantastic, and I loved the people I worked with,” Almquist says. “It wasn’t just about acting, it was about becoming a better person and getting to the depth of the material you were working with. I learned how art is influenced by culture and society and the responsibility we have as artists. The experience was without peer.”

It didn’t hurt that while studying at UM, Art met Amy Lehmann, M.F.A. ’95, while she was finishing her own graduate degree in directing. The two took classes together and ultimately fell in love while traveling the state with the comedy troupe they started together. They were married soon after moving to Tucson, where Lehmann now directs local theater productions (sometimes starring her husband) and trains attorneys to use acting and improvisational skills in the courtroom.

After relocating to Arizona, one of the first students Almquist welcomed to his resurgent drama program was Julian Martinez. Martinez attended Tucson Magnet from 1996 to 2000, and, after years of working as a professional actor, in 2016 joined the faculty as the school’s newest drama teacher.

When he thinks back on his own school days, Martinez admits he wouldn’t be where he is today without Almquist.

“My original impressions of him were, not only was he a very approachable teacher, but he was someone I could use as a role model,” Martinez says. “Without having him as a person to emulate and look up to, I think I probably would’ve gone a different direction – and probably not too good of a direction – when I was in high school.”

Martinez says Almquist has attained legend status among theater instructors in Arizona, but you’d never know it from his down-to-earth demeanor. Going from student to peer has been amazing for Martinez, though he admits being the rookie drama teacher at Tucson Magnet comes with enormously big shoes to fill.

For Almquist, having Martinez on staff provides the opportunity to reflect on his career to this point. More pragmatically, it also offers Tucson Magnet the chance to double its lineup of stellar theater events from two shows each year to four, as Martinez gets his feet wet directing productions of his own. That means more parts available for students and more opportunities for the community to see the work being done in the drama department at Tucson Magnet. Almquist says that ties back to one of the most important lessons he learned while at UM.

“Every kid has a story that is unique and interesting,” he says. “Every kid has a story worthy of being told.”

A native Montanan, Chad Dundas earned a bachelor's degree in journalism in 2002 and an M.F.A. in English-creative writing in 2006, both from UM. He works as a lead writer for BleacherReport.com and lives in Missoula with his wife and daughter.