- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

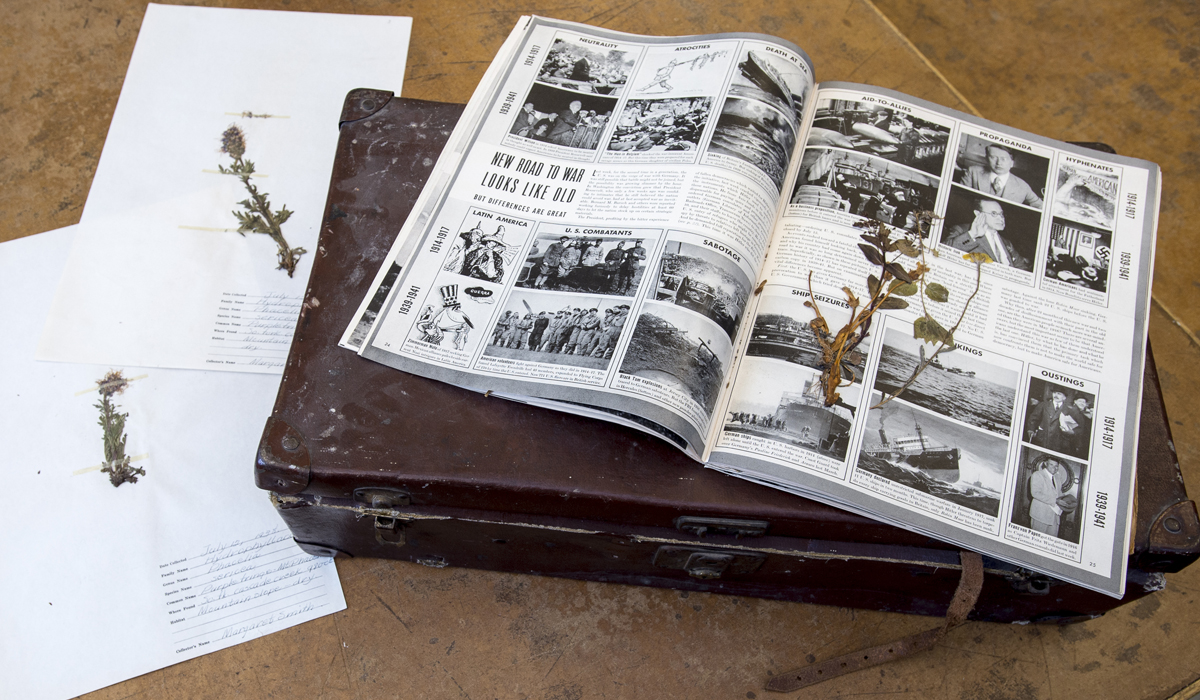

Three giant steam trunks of wildflower specimens sat in the basement of the Craighead household for fifty-some years.

The specimens, numbering in the hundreds, mostly were collected from locales throughout Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. Some were from the 1940s; others from the 1960s. They were used for a 1963 book, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers, written by the famous Craighead twins—John and Frank—and Idaho State University botany Professor Ray Davis.

“The plants are a nice bit of family history,” says Johnny Craighead, son of John and Margaret, from his parents’ home on Missoula’s south side. “But they aren’t the kind of thing that any of us would want to keep. And I couldn’t see putting them in the trash, so I took the trunks to the UM Herbarium and told them to take a look.”

The folks at the Herbarium, which is UM’s vast collection of preserved plant specimens, indeed took a look and were intrigued with what was inside.

“I usually work with specimens that have been collected in the past six months,” says Grace Johnson, UM senior and Herbarium lab technician. “It’s not too often you get old trunks of specimens delivered to your door, especially from people as prestigious as the Craigheads.”

After poring over the trunks’ contents—checking scientific data, dates, and locations—Johnson, with the help of botanist Peter Lesica and UM Natural Areas Specialist Marilyn Marler, added nearly 900 specimens to the Herbarium’s collection.

Most people know the Craigheads from their grizzly bear research in Yellowstone National Park and the National Geographic television specials that filmed their work. They also were vital in the passage of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. John, who headed the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit at UM for twenty-five years, has an endowed chair in his name at UM’s College of Forestry and Conservation.

This massive collection of wildflowers shows they were accomplished botanists, too.

“We spent a lot of time gathering plants,” says Margaret, now nearing 100 years old. “I was just always interested in them. My father was a naturalist. And I remember it was a lot of work.”

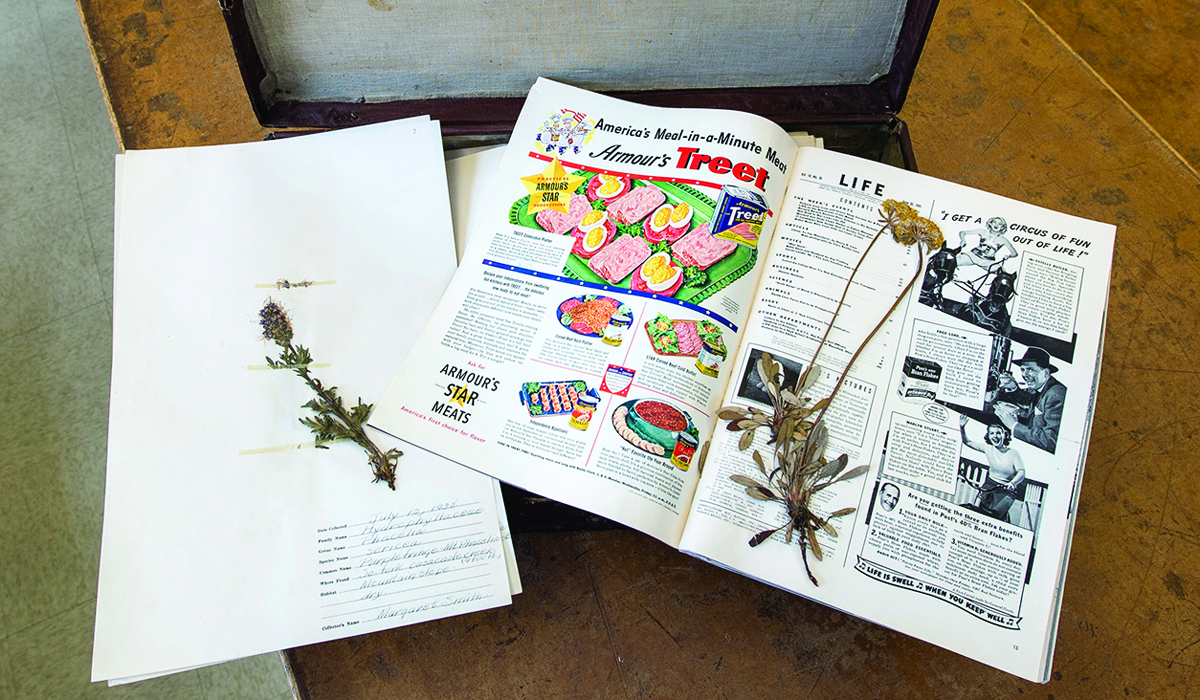

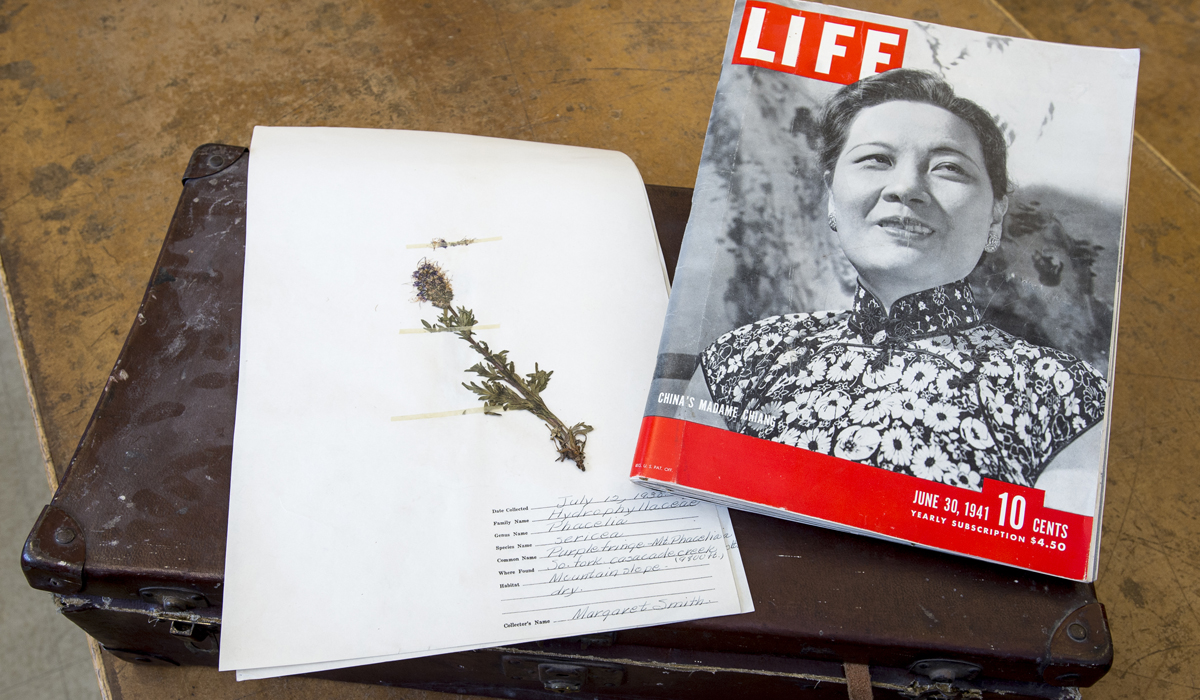

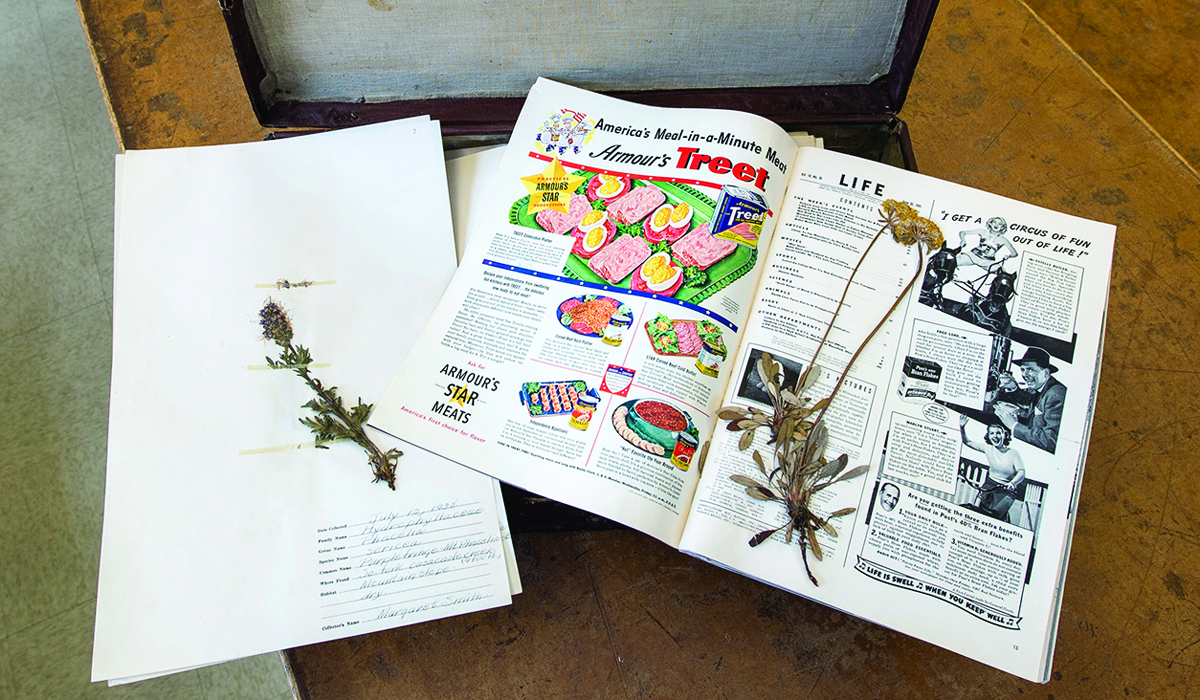

Margaret helped collect many of the specimens, and another suitcase full of wildflowers she gathered in the late 1930s and early ’40s was donated to the Herbarium. In fact, some of them were still pressed in the pages of a 1941 issue of Life magazine.

“Mom and Dad enjoyed collecting plants together,” says Johnny. “They were still basically courting at that time, and they found a mutual interest. It was something they could do together, going off into the mountains, holding hands and do a bit of collecting.”

The UM Herbarium is nestled in the corner of the third floor of the Natural Science Building. Its roots can be traced back to the early 1900s, and some of the collections are well over 100 years old. In all, more than 129,000 specimens are on the shelves.

It’s mainly used by researchers, but its purpose reaches far beyond them, with visitors including native gardeners, natural historians, artists, and school groups.

“The Herbarium has more than a dozen species new to science discovered by people involved here,” Lesica says. “And probably well over 100 species not new to science, but new to our knowledge of them being in Montana, are here, too. Just in terms of knowledge about plants in our state, the Herbarium has been essential.”

In addition to the scientific aspect, certain collections—now including the Craigheads’—add deeply to the historical value of the Herbarium.

“We are so honored to have this collection and have watch over it,” says Shannon Kimball, curator of the Herbarium. “The Craigheads will have a legacy forever, and we’re glad to have a piece of it right here.”