- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

New initiative aims to open opportunities for UM to solve the most pressing medical issues plaguing our population

Reed Humphrey remembers what people in the health care field were talking about 40 years ago – it’s the same thing they’re talking about today.

Reed Humphrey remembers what people in the health care field were talking about 40 years ago – it’s the same thing they’re talking about today.

“My hair was brown when we first started talking about preventive care,” he says, laughing.

The University of Montana professor and dean of the College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences says preventive health care has resonated with professionals and educators for a long time, but it hasn’t meaningfully impacted the way our country delivers care. In 2010, the year the Affordable Care Act came into existence, the U.S. spent $2.6 trillion on health care – $1.9 trillion of which was on preventable illnesses. Without addressing prevention, those numbers will only increase.

But as the cost of health care skyrockets, actual change in the system seems inevitable. Humphrey and other health care educators and professionals at UM are taking notice and stepping up to the plate.

“If you look at data,” Humphrey says, “the U.S. population experiences preventable illnesses on a more widespread basis and at an earlier age. Combined with an aging population and expensive late-in-life care, it is increasingly important that we focus on discovery and research that leads to improved primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of illness. We’ll need more caregivers on all levels and more population health experts engaged in primary prevention, while at the same time constantly revising our thinking on how we train our students to work in a more interprofessional way to optimize care and reduce costs.

“It’s an extraordinary, but exciting, challenge.”

Two years ago, when Humphrey became dean, he started working on a response to current health care needs. This year, he and his collaborators launched the result of those efforts: the University of Montana Health and Medicine Initiative, or UMHM. UMHM is a way for the University to be an integral part of the culture change. While larger universities with medical schools can focus on specialty care, UM is a place where undergraduate students gain academic preparation and experiential opportunities in health and medicine, and graduate students can earn health-focused degrees and engage in relevant cutting-edge research.

“The shift from a disease-based model to a wellness-based model is a significant freighter turn for health care systems,” Humphrey says. “They’re going to have to gradually change the landscape of their providers to have the kind of expertise in place to both prevent and manage disease more effectively. I think that’s where universities that have an investment in health care education have both an opportunity and a significant responsibility. And it’s not just about us producing more physical therapists or more social workers – we need them – but it’s also about enhancing their core competencies so they can work with their colleagues to meet the challenges in front of us.”

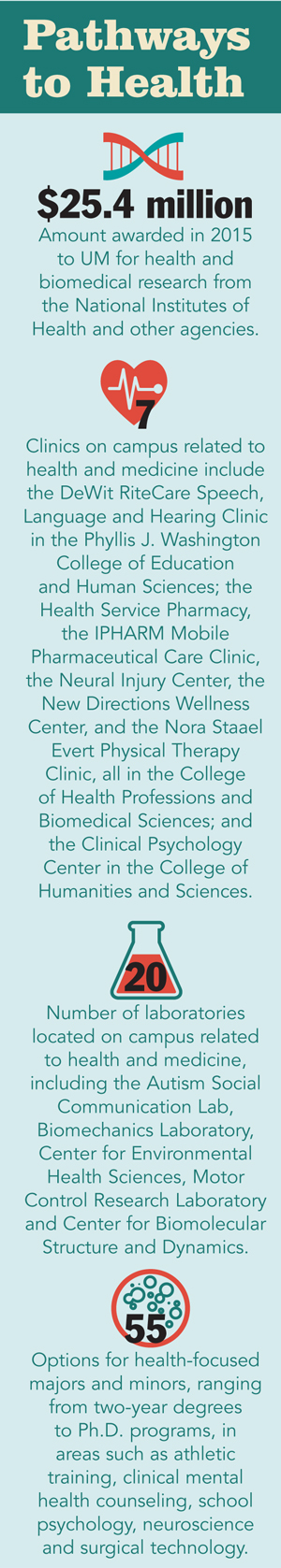

UMHM includes the creation of an online portal (www.umt.edu/umhm), which provides a virtual space to showcase UM’s seven clinics, 20-plus laboratories and 55 degree areas in health and medicine studies, from two-year to doctorate programs. The goal is to spark on-the-ground, interprofessional collaboration and open up opportunities for students, faculty and campus professionals to fortify their skills and together solve health issues for UM and the greater community. It will facilitate clinical psychology students, for instance, to work together with pharmacy, social work and physical therapy students, among others.

“Programs at UM in health evolved rather organically over the years and live in different colleges,” Humphrey says, “so we needed a new approach to bring them into cohesion. That’s UMHM. Our ability to communicate across campus and knit those programs together under a singular brand will allow greater bandwidth.”

UMHM is a way to recruit students, but more importantly is a way to improve the educational experience and employment options for the health and medicine students already enrolled. The initiative includes a sequence of activities and seminars focused on big-picture aspects of the system like the economics of health care.

“If you’re interested in a career in health care, through our UMHM Community of Learners project you can understand what health care looks like now and what’s it going to look like in the next five to 10 to 20 years.”

The enhancement of UM’s labs and clinics inevitably will lead to more health and medicine programs. It also allows students, faculty and professionals to lead the way when it comes to the national conversation on how we fix health care.

“Our educational system has to resonate with what the hospitals need and what society needs and with what the data show,” Humphrey says. “And when you have a university that has a cluster of programs on campus, you can execute interprofessional education. In many respects we have an obligation to do that – it’s in our mission to serve Montanans.”

Holistic education

Small towns in Montana – and there are a lot of them – have a hard time drawing in young family physicians fresh out of medical training. Part of the issue is doctors tend to settle in the places they were trained and, until a few years ago, Billings housed the only family medicine residency program in the state.

In 2013, UM’s Family Medicine Residency of Western Montana accepted its first class, and its addition to the state was in direct response to the dearth of primary care in underserved areas. It’s an accredited, three-year program, sponsored by UM and located at Partnership Health Center in Missoula and Flathead Community Health Center in Kalispell. It’s also engaged with three hospitals: Kalispell Regional Medical Center and Missoula’s St. Patrick Hospital and Community Medical Center. It’s an unusual residency model because UM doesn’t have a medical school, but that situation turns out to be beneficial.

“It provides a politically neutral playing field between the three hospitals,” says Dr. Ned Vasquez, the residency’s program director. “And it provides an academic home that’s embedded in the College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences. It’s a really nice way for young physicians to interact with students in pharmacy, physical therapy, social work, public health and psychology and have dialogue.”

Dr. Megan Svec, who graduated in July as part of the first residency class, grew up in Anchorage, Alaska, and recently took a position in Ronan. The leap from big town to small community is exciting, she says. And it was the residency that prepared her for it.

“I think it was an incredible experience,” she says. “The faculty are really transparent, and we got to have a role in shaping the program – it’s a lot more collaborative. Doing the rotation in Ronan was an eye-opener in how admirable rural traditions can be. My patient size will be the same as it would be if I were in Missoula, but it’ll be a tighter community with continuity.”

UMHM highlights the relevance of the residency program while providing extra opportunities for the residents to add skills to their toolbox. Importantly, UM’s College of Humanities and Sciences provides the liberal arts-style, broad-based education in medical history, social sciences and psychology. Students who might want to work in medical clinics serving migrant populations would benefit from cultural and language classes. The college is also home to the philosophy department, which deals with ethics – an important part of medicine and the health professions.

Chris Comer, dean of the College of Humanities and Sciences, says rural medicine is an area that would benefit from rural sociology, getting a sense of how services are provided, how they cope in sparse environments and how they interact with urban areas.

Chris Comer, dean of the College of Humanities and Sciences, says rural medicine is an area that would benefit from rural sociology, getting a sense of how services are provided, how they cope in sparse environments and how they interact with urban areas.

“If you think about the fact that UM is a liberal arts-based university, it makes good sense that training students here in both health and medicine would be broader than it would be at other places,” Comer says. “Students would be encouraged to train in a very holistic way to get a lot of the humanistic aspects that make them wiser and more humane health practitioners in the end.”

The dawn of UMHM means connecting the dots in new and exciting ways, but with a practical goal: to engage with the greater health care field in a way that fits the newest innovations in patient care.

“I think the challenge for us will be to cultivate that interaction in more serious ways,” Comer says, “so the students really feel like they’re getting an education of the whole person – so they can be providers who treat the whole person.”

Breaking silos

A few years ago, media outlets began reporting on research related to NFL players and concussions, and it caught the country’s attention. The idea that multiple concussions could lead to brain disease and death for athletes opened up a whole new conversation about the importance of detecting, and ultimately preventing, traumatic brain injuries.

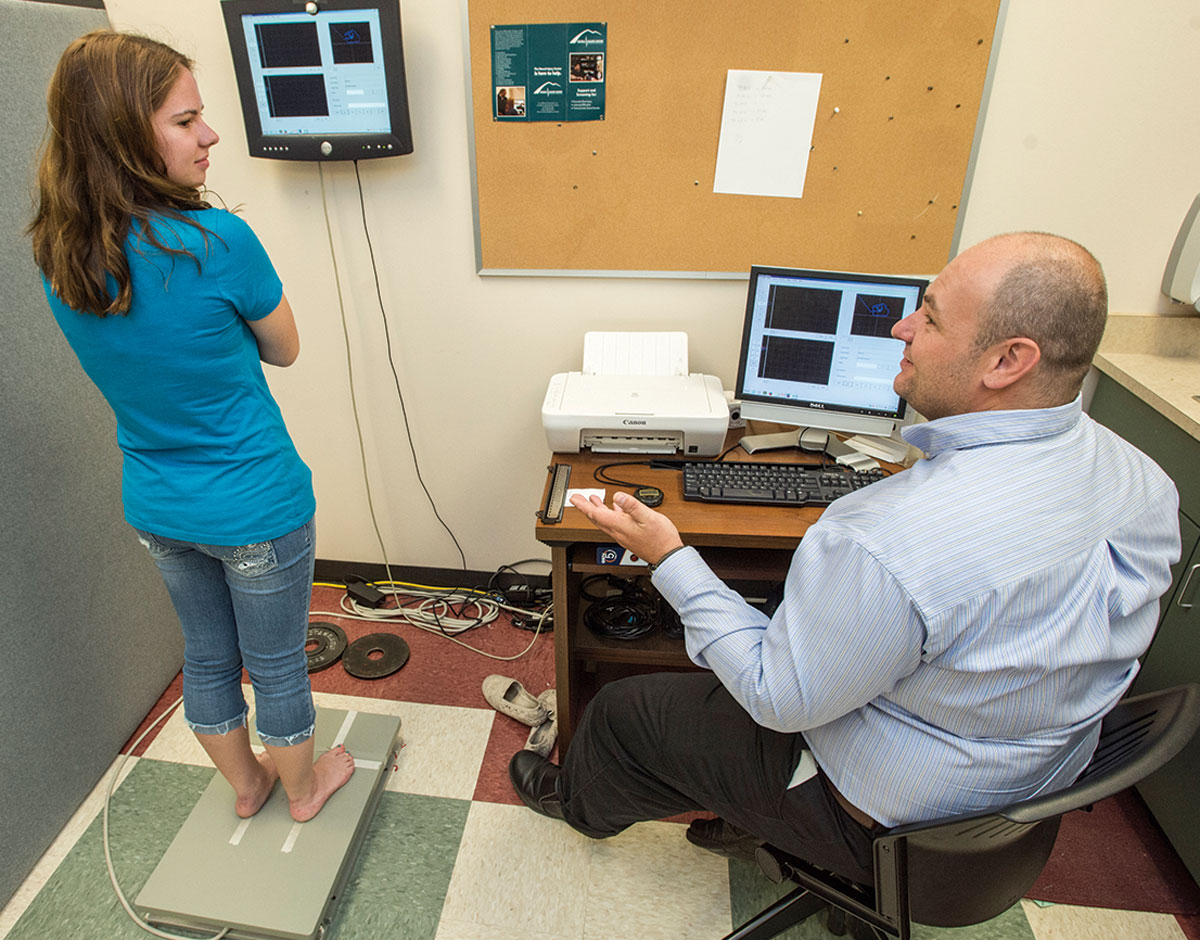

At UM’s Neural Injury Center, a group of researchers that includes Alex Santos, Thomas Rau, Sarj Patel, Adriana Degani and Cindi Laukes, focuses on the brain health of our community – in particular, war veterans – and developing tools designed to diagnose mild head injuries that, despite the name, can cause serious long-term effects to the lives of survivors. They employ high-speed cameras to track eye movement, for instance, and take their patients through cognitive evaluations, balance assessments, memory checks and neuropsychological testing.

“A lot of people recover from a concussion,” Santos says. “But those who don’t recover well can have symptoms that include difficulties with reading, making decisions, anxiety and changes in mood. All this affects the ability of this subject – this survivor – to engage in school work and to engage in athletics. And one of the things that happens is your brain can become slower, so the trauma can increase the likelihood of you to have another one.”

Developing and implementing these tools for detection requires collaboration among people on and off campus, and in that way, the NIC is a small-scale model of what UMHM aims for. Universities always face the challenge of making meaningful connections between departments, but centers are designed to break down silos, and since its inception in 2014, the NIC has worked to foster relationships on campus. Some of those relationships are more obvious, like their collaboration with the School of Physical Therapy, the School of Pharmacy, and Biomedical Sciences. Other connections make sense once you consider that the NIC develops all of its own tools.

“Anytime you’re developing a certain tool for diagnostic purposes, we have to code,” Santos says. “We have to sit at a computer and work at the mathematics behind it. So computer programming, virtual reality studies – they’re all in the realm of our laboratories. And so you can see if you start covering as much area as we do, from the cellular level to the behavioral level, we’re going to encompass most of the departments we have on campus.”

The hope with UMHM is that more doors will open between centers, labs and departments, resulting in a synthesis of expertise and students trained in an integrative way in all areas, including traumatic brain injuries.

“If this initiative develops in the way it’s envisioned, it will bring in more partners just by its nature,” Laukes says. “More people becoming involved and coming together will make mutual collaboration a lot more possible.”

Community service

When it comes to serving the community, Missoula’s hospitals have become ever more competitive. Last year, St. Patrick Hospital opened its Family Maternity Center after 40 years of allowing Community Medical Center to be the sole provider for in-hospital baby deliveries. But at a recent dinner hosted by Humphrey and UMHM, hospital CEOs Jeff Fee of St. Pat’s and Dean French of CMC sat at a table with Mayor John Engen and other members of the community to discuss how they could work together with UM’s health and medicine programs.

“Health care delivery is going to transform over the next decade – if not by next week – and the health care workforce is not in place today; it needs to be trained for tomorrow,” says Dr. David Lechner, president/chief medical officer of Community Physician Group. “One of the nice things about being here in Missoula is we can be on the forefront by working with the University around developing what that workforce is going to look like.”

That landscape is coming into focus even now as UM does a feasibility study on instituting an occupational therapy program. The community is in need of more social work and case management to help with preventive care – keeping people out of hospitals in the first place.

Engen says the city is interested in working with UM on healthy kids programs and population health issues.

“They’re putting a bunch of brain power and a bunch of energy behind that brain power to take care of Missoulians,” Engen says. “The timing seems to be conspiring in the best sense of the word to put us together so we can think about ways to deploy all these resources available on campus and get them out in the community.”

Like everywhere else in the U.S., preventive care is the philosophy for Missoula public health. It’s also personal for Engen, who has publicly struggled with weight.

“If we can get kids engaged in better habits and better experiences earlier on, maybe they don’t have bariatric surgery when they’re 50 years old,” he says. “Maybe they don’t develop diabetes and maybe they don’t end up with all sorts of chronic ailments that take a toll on the system, but also take a human toll. I’m really tickled that UM wants to be out in the community working with the other institutions and anyone else to make lives better.”

UMHM is about creating a community of learners. And it’s about being able to predict when change is in the air – and prepare for it now.

“It’s exciting for me,” Humphrey says. “I recall an author once said, and I’ll have to paraphrase a bit here: ‘The future is not invisible. Threads of its design are readily apparent’ – and that’s true in health care. UMHM is designed to honor that concept – it’s exciting that the University of Montana can move innovative ideas into reality.”