- Editorial Offices

- 325 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

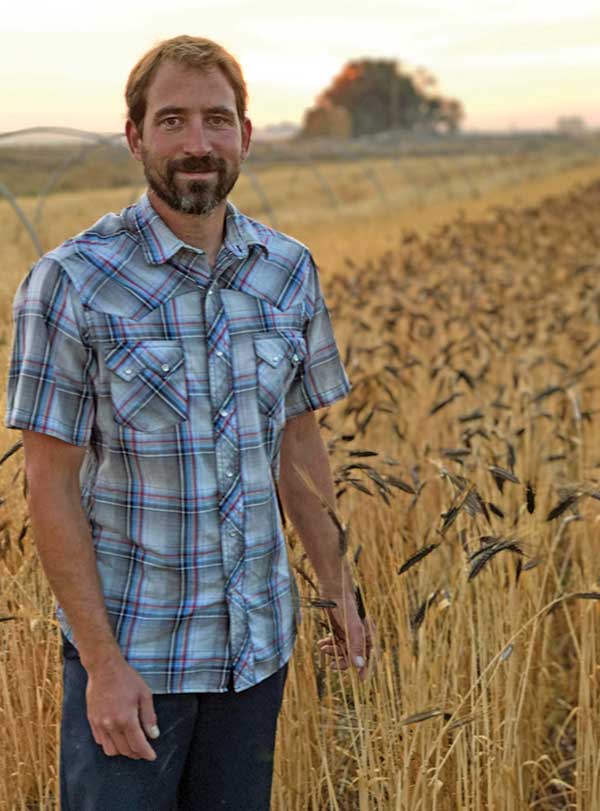

An insider’s view of what ‘renegade farming’ looks like in Montana

When most people conjure the image of a farmer, it’s a specific one.

Maybe it’s an overall-clad, broad-brimmed-hat-wearing organic vegetable grower steering a wheelbarrow. Or, a ballcap-wearing guy in a button-up shirt hauling grain or driving a big-boom sprayer.

But the portrait of the American farmer is more nuanced and diverse than most people realize – even more than I realized. And I grew up with one.

As a child, a farmer was a quiet, tall guy with weathered skin and strong hands – my dad.

He drove big combines, tractors and a three-quarter-ton Chevy. (Only a rancher drives a dually.) He grew wheat, maybe a little barley, and ate sandwiches on white bread on his tailgate in the middle of the field.

There’s some truth in that picture of a farmer.

According to the most recent USDA Census of Agriculture, finished in 2012, the average American farmer is 58 years old, white, male and likely grows corn or soybeans. Corn and soybeans accounted for 43 percent of the total cash receipts of farm income in 2015, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service.

But that’s not the whole truth.

There really isn’t such a thing as an “average” farmer. The landscape of American agriculture is more complex – biodiverse, you might say – than the numbers, or the stereotypes, could ever show. It takes a lot of different kinds of people and a lot of different kinds of farms to grow a nation’s food. In other words, American farmers are not a monocrop.

If there’s one message I hope readers take from Liz Carlisle’s book “Lentil Underground” – this year’s chosen Griz Read book at the University of Montana – it’s that.

Carlisle, who grew up in Missoula, where her parents both worked at UM, fell into the book by chance.

After getting her undergraduate degree at Harvard, she had an early career as a country singer crisscrossing the United States. It was then she saw a disconnect in the narrative of rural places and what was actually happening on the ground. So she went to work for U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, an organic farmer who spoke eloquently and passionately about the future of agriculture.

That’s how she met the first “renegade farmers” she profiles in the book and was struck by the difference they were making in Montana. She left Tester’s office for graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, and decided exploring what she saw during her D.C. work from the fields of her home state would be her thesis. She spent years in big fields, talking to these farmers about soil fertility and climate change and crop rotations and markets.

But the story she heard was bigger than all of that. And it got bigger and bigger until it was clear: This wasn’t just research. This was a book.

“I had this background as a country singer. I have this deep love of narrative and storytelling and a belief that it’s a key part of what makes us human,” says Carlisle, now a lecturer in the School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences at Stanford University.

“So when people were telling me about how they were farming and the history of the movement and they were doing it in this beautiful narrative way, I thought, ‘Well, this is obviously communicating to me and is very moving to me, and I would like to pass it on to others in the same narrative form.’ There’s a lot of great content, but also in the form – in the stories – there’s a lot of wisdom and a lot of power to inspire and inform.”

When Liz Carlisle found out her book about sustainable agriculture in Montana “Lentil Underground” was chosen as this year’s common Griz Read, she was thrilled.

She grew up a few blocks from campus, and both of her parents, Ray and Lynne Carlisle, worked at UM.

Ray directed the TRiO program on campus – a federal program aimed at helping students with disadvantaged backgrounds succeed in higher education. He wrote the first grant to bring the program to UM in the 1980s.

“Something he worked really hard on was making books – class materials – accessible to low-income students, and so that was very much in my mind when I got asked to do this,” Carlisle says.

So Carlisle donated her honorarium from the book – which UM’s Grizzly Riders organization matched – to make the book free of charge for first-year students.

“That’s a really sweet connection for me,” she says.

The book’s financial success was a bit of surprise, Carlisle says with a laugh. Whatever she makes on it, she wants to give back.

She used some of the advance money to pay for the farmers featured in the book (my husband included) to join her in California for a series of readings and launch parties where they talked food, farming and Montana with the likes of Michael Pollan, Carlisle’s mentor and the author “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” and “In Defense of Food.”

“The reverberations of those kinds of opportunities to convene are just so powerful,” Carlisle says, “so anything financial that comes out of this book, I actually want to plow back into its purpose."

That purpose, Carlisle says, is manyfold – like helping people connect with where their food comes from and who grows it, or highlighting what she calls a “pilot project” for the future of a sustainable food system. But also, she says, it’s about showcasing the work being done in her home state.

“There was a lack of understanding of what sustainable agriculture looked like in the middle of the United States,” Carlisle says. “There was more of an understanding for people of farmers’ markets and greenbelt cities and some of the stuff around the produce system and dairy. But the feedback I’ve gotten from people is they’re just so encouraged to learn about third- and fourth-generation farmers in eastern Montana who are conceptualizing how to create a more environmentally friendly food system that’s good for public health.

“I’m a proud Montanan, and I often feel like we’re sort of underappreciated sometimes by major progressive movements in places like San Francisco that imagine there’s just not that much going on in rural places, and there really is."

“Lentil Underground” at its core follows the history of sustainable agriculture in Montana through the lens of a community of farmers who sparked a movement that is changing how farmers farm in Montana.

But it’s doing even more than that. It’s helping change the narrative around American agriculture, making it more accessible, more inclusive.

Growing up, I didn’t think farming was for me, partially because I was under the false assumption that it was something done one way by one specific group of people. I spent my 20s running away from the farm life I knew and loved.

But one day, my now-husband, Jacob, who also grew up in the “Golden Triangle” of central Montana, asked me to go to an agriculture conference. There, I met many of the farmers and people who make up the movement depicted in “Lentil Underground.”

Jacob and I had both recently moved back to Montana after leaving the state to “make something” of ourselves. We’d gotten the message familiar to most small-town kids like us that to be something, you had to go somewhere – as in, somewhere else. So, we left. But the call of Montana was too strong for both of us, and we moved back, independently, in 2005.

Jacob went back to UM to get his master’s degree in environmental studies, and I returned to Missoula to start a magazine about the Rocky Mountain West with a former professor of mine from the School of Journalism.

Even in Missoula, though, we couldn’t shake the feeling that we still weren’t really “home.”

We both were researching and writing about rural communities. The more we did, the more we realized how much we both missed the sunsets, the space, the sense of community. And the food.

Jacob was bitten by the farming bug at UM’s PEAS Farm, and once he took environmental studies Professor Neva Hassanein’s Politics of Food course, he was all in. His master’s portfolio involved working on a sustainability strategy for “Lentil Underground” protagonist David Oien, the founder and CEO of Timeless Natural Food, a company that works cooperatively with farmers in the growing and marketing of high-quality lentils, peas and specialty grains. Oien, by the way, earned a bachelor’s degree from UM in 1973.

Sometime midway through grad school, Jacob told me he wanted to farm.

Given my family farm’s struggles and my promises to my 16-year-old self never to go back to that, it took some lobbying on Jacob’s part to bring me around to the idea.

He asked me to attend this conference – the annual Montana Organic Association’s meeting, which happened to be in Missoula that year. There, I met the network of Liz’s “renegades,” a somewhat ragtag crew of farmers of all shapes, sizes, crops, genders, growing methods, backgrounds and political persuasions.

That diversity is important, Carlisle says.

“I think that’s one of the reasons I wanted to tell the story,” Carlisle says. “Because sometimes from the outside, I think people perceive the food movement or organics or sustainable agriculture as being restricted to a certain kind of cultural swath – certain politics and even certain ways of dressing and talking. That’s just a misconception, but I think it has some consequences that prevent us from moving forward.”

Just like diversity is the key to a farm’s soil, crops and bottom line, it’s good for the whole system.

“There’s this basic ecological principle that resilience and diversity are linked – that you need diverse ecological communities to have resilient natural systems,” Carlisle says. “I think it’s clear to the farmers that I’ve spoken with, as well as clear to me, that that’s equally true in human communities – that diversity is a really important part of the strength of this organic agriculture movement in Montana that sort of started from nothing and now is kind of a big deal."

Once people are able to see sustainable agriculture as holding a bigger umbrella, “it seems possible and it also seems accessible to many, many more people,” Carlisle says.

This community certainly made me think there was room for farmers like Jacob and me. So after we talked to Oien (on our honeymoon) about him leasing us some ground on his place near Conrad, we packed up our stuff, I quit my job and we moved home to the Golden Triangle to start our farm.

Across the country, the number of new farmers has been on the decline – so much so that government officials, ag advocacy groups and even leaders in the food business are working hard to encourage and support beginning farmers. From the 2012 Agriculture Census: “In 2012, the number of new farmers who have been on their current operation less than 10 years was down 20 percent from 2007.”

That tide may be waning, however. The reasons for that are varied and relatively anecdotal, but whether it’s the work being done by beginning farmers across the country, the increased desire to know where food comes from, an inherent need of a new generation to root themselves to the land or an increase in the opportunities for how to farm and the technologies and markets that facilitate it, we are seeing more new farmers on the land.

And while Montana State University traditionally has produced the bulk of Montana’s farmers, in the past decade or so, UM also has started filling that pipeline.

“Frankly, MSU faculty have come to us to try to figure out why we have so many students interested in food and agriculture, when traditional majors, like agronomy, have been on the decline at many agricultural colleges,” Hassanein says.

Part of what attracts UM students to agriculture, she says, is wanting to be part of a growing movement of producers who want to connect deeply with their communities.

“Our students tend to come from nonfarm backgrounds, but everyone can relate to food so the topic really resonates with them,” Hassanein says.

“They are less interested in conventional commodity production and much more excited about how food connects us to each other and to the land. In today’s society, so many of us are disconnected from our food and the natural world we depend upon to survive. A lot of our students want to turn that around as they discover these issues and learn about growing food.”

Western Montana is peppered with farms started by people who got into farming much like Jacob did – at UM’s PEAS Farm, or in one of the environmental studies classes on campus. Many of those farms are small, diversified, direct-market and rooted near one of Montana’s urban cores.

Others are also out here where Jacob and I are – in more rural places – where it’s been difficult during the past 20 years to attract young people back to the farm. That’s one of the more interesting parts of the book, Hassanein says.

“In the media and elsewhere, there’s a lot of emphasis on eating ‘local’ right now,” says Hassanein, who nominated “Lentil Underground” for the Griz Read program. “That’s great, but the book helps us understand that not all farmers can market locally and that it is also important to support organic growers who produce crops like lentils.

“In the book, you learn about how important it is to build soil quality. Soil is literally the lifeblood of humanity. In turn, the reader learns about how sustainable agriculture can also help sustain our rural communities – too many of which have been in decline as industrial agriculture has taken hold in the last century.”

Casey Bailey, one of the farmers in “Lentil Underground,” grew up on a farm near Fort Benton. He left to study religion and music in Santa Barbara, California, but came back to finish his music degree at UM.

As he went after another degree – in education – he crossed paths with Dan Spencer, a professor in environmental studies. Bailey immersed himself in the intersections of globalization and social and environmental justice. Then he studied soils – where all of those things connect – with Tom DeLuca, now the dean of UM’s W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation. As Bailey puts it, DeLuca “really brought soils to life for me.”

By studying, volunteering on farms, traveling and starting a community garden as the youth director at a church in Great Falls, Bailey found his calling – a calling back to the farm.

“Along the way I realized that in religion, music, art or agriculture, there is no ‘right way,’” Bailey says.

He found a community of like-minded farmers – the same community Jacob and I had found and been inspired by. Bailey’s first organic crop was a 30-acre field of French green lentils for Oien and Timeless Natural Food.

“I knew what I wanted to do when I started discovering people like Dave,” Bailey says. “Dave helped to give a kind of wild, go-get-’em center to pivot from.”

“Go get ’em” is exactly the way to describe this community in Montana. It’s small, but mighty. Diverse, but not splintered. Positive, but not Pollyannaish.

And it tells the truth about Montana agriculture that, as Bailey says, like life, there’s not just one “right” way to do it. Nor is there just one “right” kind of person to do it.

It’s one of the things that makes “Lentil Underground” not just a good story, but a powerful one.

“Rhetoric – and language and storytelling – is really important, really critical, in moving forward with our farming systems and food systems,” Carlisle says, “because certain people practicing agriculture have been rhetorically excluded from the category of farming, including small farmers who’ve been called gardeners, organic farmers who have at various times have been called hobby farmers or not real farmers.

“Early in the time the book’s talking about, organic farmers weren’t considered part of the farming community, women farmers [weren’t considered part of it either]. I think the diversity that we need in agriculture – to actually sustain ourselves as a people – includes certain kinds of agriculture that have been rhetorically excluded from the category of farming. And, by being rhetorically excluded, they’ve also been materially excluded – excluded from resources and excluded from communities that share knowledge and social capital. So it’s really critically important to include all the diversity of agriculture in the way we talk about it and understand it.”

Finally understanding that is why, nearly 20 years after I first left the Montana prairie, I’m sitting in a field, my own skin now weathered, eating a sandwich made from sourdough bread my farmer/baker husband baked – with the grains we grew and milled – doing something I didn’t think was possible: calling myself a farmer.