- Editorial Offices

- 103 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2522

- themontanan@umontana.edu

- Icons By Maria Maldonado

Imagine if Mount Sentinel above the University of Montana campus was turned into a Mount Rushmore of honorary Missoulians. Who would be on it? Votes would surely go to the pioneering men and women who shaped Missoula’s values and culture, like U.S. Representative Jeannette Rankin, Bitterroot Salish Chief Charlo, smokejumper pilot Bob Johnson and writer Norman Maclean.

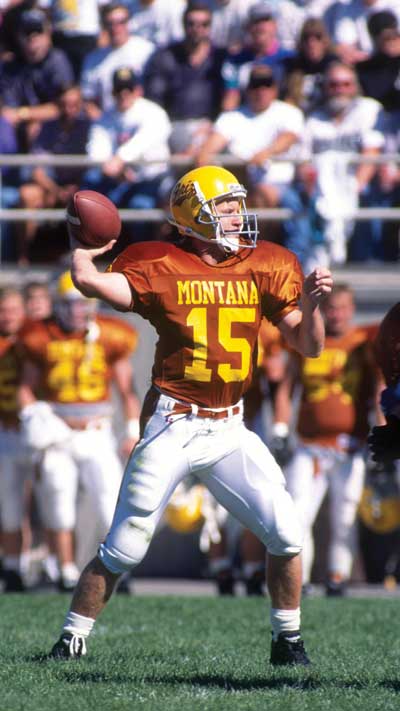

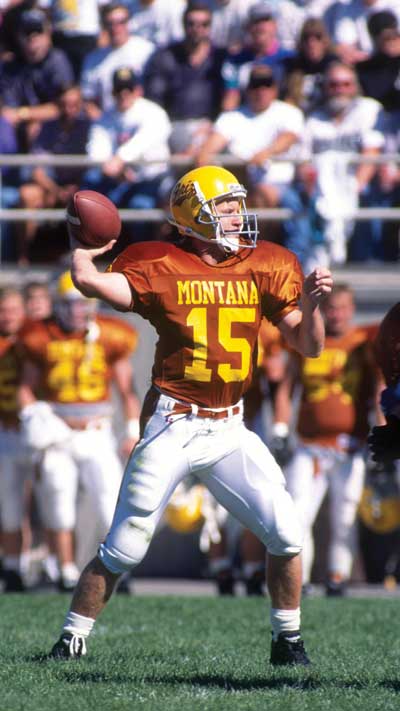

But the most votes might go to a man who in the mid-1990s wore a sepia-toned number 15 and did for Grizzly sports what no one had done before. He is quarterback Dave Dickenson. In 1995, he led a corps of Montana athletes, like a reverse of the westering pioneers of yore, east from the sparkling Rocky Mountains down to the humid banks of the roiling, brown Ohio River in Huntington, West Virginia, for a national championship game. The Grizzlies had never won it before. A fervent cadre of fans from Missoula followed – forebearers of a culture that would blossom in the next generation. The tale is Grizzly mythology now. On a fourth down on the 50-yard line with his team down 20 to 19 and 3:14 left to play, Dickenson took a snap. With the special intuition that allowed him to throw a record-setting 5,676 yards and 51 touchdowns that season, he waited. Waited as three boulder-sized linebackers charged him after he had already taken a beating all game. Waited until a bullet’s path opened up to fire the ball into the hands of UM receiver Mike Erhardt, who ran it more than 20 yards.

The tale is Grizzly mythology now. On a fourth down on the 50-yard line with his team down 20 to 19 and 3:14 left to play, Dickenson took a snap. With the special intuition that allowed him to throw a record-setting 5,676 yards and 51 touchdowns that season, he waited. Waited as three boulder-sized linebackers charged him after he had already taken a beating all game. Waited until a bullet’s path opened up to fire the ball into the hands of UM receiver Mike Erhardt, who ran it more than 20 yards.

A few plays later, Andrew Larson kicked the field goal that changed Missoula from being a mountain town with football into a football town with mountains. In Dickenson, the modern Griz Nation had its George Washington. They reverently nicknamed him “Super Dave.”

“The cool thing with Montana celebrity is anytime anyone does something good from Montana, the whole state claims you and believes in you,” Dickenson says by phone from his home in Calgary, Alberta. “I was very proud to be a part of something we’d never done. You can only be first at so many things. When you’re the first team to win something, they can never take that away.”

The national championship was Dickenson’s greatest achievement in America. After college he went north and became a superstar in the Canadian Football League. That feat briefly brought him back to America for a chance at the NFL. That, however, became his greatest disappointment.

Then in January of this year, Dickenson learned that his American career had been dramatically reconsidered on the national level. He was selected for the most elite prestige he is eligible for in his home country. He was voted into the College Football Hall of Fame. It’s a distinction that for him carries extra meaning and made him think about where he might do next.

“I’m just very proud,” he says. “I just can’t wait.”

Dickenson was born into a tight-knit family in Great Falls in January 1973, the third of three children to a husband and wife who worked as schoolteachers. By seventh grade he weighed just 72 pounds, too few to make the top football team at North Junior High School. His sister Amy Umbarger, now a high school science teacher in Pendleton, Oregon, remembers him as a “red-headed, freckle-faced, pesky younger brother.”

“He always wanted to keep up with us,” she says. “We made him work hard.”

His size masked a fierce competitiveness. It showed itself in everything from his collection of bowling trophies to his 4.0 GPA. His neighbor, Tony Arntson, who went on to quarterback for the Grizzlies and was a role model for Dickenson, took early note of this spirit.

“He just would not let anybody beat him in anything – from checkers to the football field,” says Arntson, now a coach at Carroll College in Helena. “Dave spread that attitude through all of his teammates.” In his final years of high school, Dickenson led the Charles M. Russell team to back-to-back state AA football championships. In 1993, he became UM’s starting quarterback despite his weight barely doubling since junior high.

In his final years of high school, Dickenson led the Charles M. Russell team to back-to-back state AA football championships. In 1993, he became UM’s starting quarterback despite his weight barely doubling since junior high.

“I wanted to go to the top level in Montana and see if I could make it,” he says.

At UM, Dickenson was paired with the perfect coach in Don Read. Read recognized Dickenson compensated for strength with smarts and skill. He could decipher in a flash everything an opposing team would do. Lacking a rocket launcher for an arm, this David made his a Goliath-killing sling. On the field he fearlessly dodged tacklers until he could bullseye one of his receivers.

“Don Read was willing to play to my strengths,” Dickenson says. “I can picture coverages, I can picture plays, I can see how things fit. The creativity I have is I would never give up on a play, I was not worried about injury of my body, no regard for my well-being, I was always willing to lay it on the line.”

Jon Kasper ’97, who got to know Dickenson as a high school teammate, as a sportswriter for the Missoulian newspaper and later as an assistant commissioner for the Big Sky Conference, says that from the start Dickenson’s perception of plays was superhuman.

“He understood the game in such an advanced way,” Kasper says. “He was a leader. People followed him. He was a winner.”

In 1993, the Grizzlies won the Big Sky Championship for the first time since 1982 and for only the fourth time in history. The next year they reached the I-AA playoff semifinals for only the second time in history. Then came that fabled 1995 season. Super Dave became the most famous man in Montana. To legions of fans, he still is.

“I took some friends down to Montana after I was up here in Canada, and I said, ‘Hey guys, it’s going to be a little bit crazy.’” Dickenson says. “They thought it was a joke, but everywhere you went you’re getting honks and, ‘Hey Dave!’ I got across the border once without a passport. I still get calls from guys back in Missoula, and they still watch all my games. It’s pretty amazing to me.”

The national championship made Dickenson, who graduated with a 3.9 GPA, decide against becoming a doctor and instead pursue a career in football. Playing for the Calgary Stampeders in 2000, Dickenson won the Canadian Football League’s Most Outstanding Player Award.

That led him in 2001 to the opportunity of his dreams: to come home to America and play in the NFL. Dickenson, then 28, wanted to do what he had done in every other football program he touched. Up to that point, he had not only bested all expectations, he had obliterated them. This weighed on his mind.

“I actually put a lot of pressure on myself from the get-go,” he says. “It’s your last name, your family. Once you’ve had a lot of success, you start to ask, ‘What if it doesn’t go well? The standard is set so high.’”

He never got his chance. He was picked up and then dropped by four NFL teams over two years. Montana’s greatest quarterback played well in exhibition games only to never get to play a single second in the regular season. It burned him then. It burns him now.

“That probably is the one negative of my career,” he says. “I never got a live snap. I never made it.”

He says he felt bitter about the way he was treated in the NFL. In 2003, he went back north. He signed with the British Columbia Lions and in 2006 led them to win the Grey Cup, Canada’s Super Bowl.

“I really needed that,” he says. “You need that championship as a starting quarterback to make you feel that what you’ve sacrificed and what you went through is worthwhile.”

By 2008, Dickenson’s trademark talent for holding onto the ball until a receiver opened, even if it cost him a skull-rattling hit, became a liability. Though he was by then the CFL’s all-time leader in passing efficiency, he retired because he suffered too many concussions. That fact has left the former medical student worried, but regretful of nothing.

"I would do it all again,” he says.

No sooner had he hung up his uniform than he was hired as a coach. The Stampeders brought him on as their offensive coordinator in 2011. In 2016, he was given the job of head coach. He immediately won the Coach of the Year Award.

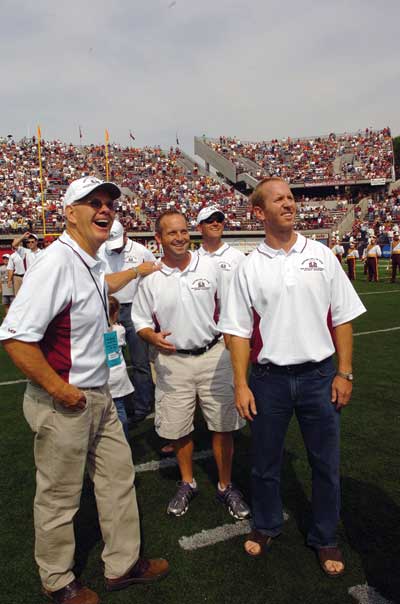

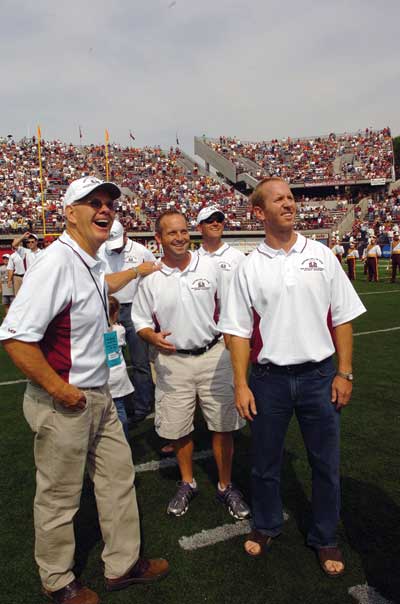

Halls of fame and other elite merits have come his way. In 2002, he was inducted into the Grizzly Sports Hall of Fame. In 2013, the Big Sky Conference named him its greatest male athlete. In 2015, he joined the Canadian Football Hall of Fame.

There was just one missing. By some metrics the College Football Hall of Fame is the toughest of all. According to the National Football Foundation, of more than 5 million people estimated to have played, coached or otherwise participated in college football, fewer than 1,000 are in the hall. Dickenson himself called College Football Hall of Fame inductees, “a group that I never thought I could be a part of.”

The only other Montanan ever inducted into the national hall is UM’s “Wild” Bill Kelly ’26, a quarterback and talented open-field runner. Kelly played in the young NFL from 1927 to 1930, but he tragically collapsed and died suddenly while watching a football game in New York at the age of 26.  The drive to get Dickenson to the hall began with his brother Craig. Craig Dickenson, now a special-teams coach for the Saskatchewan Roughriders, calls his brother Dave “as good as there was in his day.” He felt that after the NFL disillusionment, his brother deserved a nationwide honor in his home country.

The drive to get Dickenson to the hall began with his brother Craig. Craig Dickenson, now a special-teams coach for the Saskatchewan Roughriders, calls his brother Dave “as good as there was in his day.” He felt that after the NFL disillusionment, his brother deserved a nationwide honor in his home country.

“The acknowledgement of making the College Football Hall of Fame validates what he did in the U.S.,” Craig Dickenson says.

In 2015, Craig Dickenson called Dave Guffey, then UM’s sports information director. Guffey submitted a formal application to the College Football Hall of Fame. Three years later, Dickenson was voted in.

“It puts the final stamp on just how great he was, how iconic he was,” Guffey says. “It’s deserving; it’s about time.”

Added National Football Federation President & CEO Steve Hatchell, “There is no doubt that he is one of the best to have ever played college football, and his accomplishments deserve to be immortalized.”

Dickenson’s wife and two children, his parents and his siblings will travel to New York City in early December for the induction ceremony. Dickenson says he is once again proud to have brought esteem to his family name. His sister Amy pointed out that all Dickensons played a part.

“We always pushed him,” she says. “We deserve a little bit of the credit for this, too.”

The question always comes up: Would Dickenson ever return to Montana to coach his alma mater? Working as a coach in Canada while receiving honors for his play at UM makes him think about it. The team, he says, “is in my blood.”

“But let me say I know the Griz are in good hands right now with Bobby (Hauck),” Dickenson says. “He’s a great coach, and I’m excited to see what he can accomplish this year. And I’m certainly not in a hurry to leave Calgary, but I do always have Griz football on my mind.

“And it may not be in my best interest to ever coach in Montana, as it may cause hard feelings if it didn’t work out. Really, I have no unfinished business in Montana, just great memories.”

Craig Dickenson says that, ironically, his brother, always protective of his family time, created the conditions that make him hesitate. In the past generation, Griz coaching has shifted beyond intensive cultivation of native-grown alchemy to include time-intensive recruiting of top talent from far away.

“Part of what makes the job hard is what Dave and his teammates did,” Craig Dickenson says. “The winning tradition he started, fans there have gotten used to 10-2 and 11-1 seasons.”

Dickenson knows that if he didn’t do as a coach what he did as a quarterback, it would never tarnish his playing legacy. But it would become its epilogue. Fortunately for the Griz fans who would love to see his face above the stadium, or better yet back in it, he never let fear stop him from a play.

He continues to wait for that opening.

Nate Schweber is a freelance journalist who graduated from UM’s School of Journalism in 2001 and lives in Brooklyn. His work appears regularly in The New York Times. He has written for Rolling Stone, Al Jazeera America, Anthony Bourdain’s Explore Parts Unknown, Narratively and Trout. He is the author of “Fly Fishing Yellowstone National Park: An Insider’s Guide to the 50 Best Places.” He sings in a band called the New Heathens.