Lee-Gray Boze, at 5 foot 10 and wiry in frame, might not be who you think of when you think of a caver – or an arctic explorer for that matter.

Always wide-eyed and grinning, sporting a coarse red beard, perhaps it’s Boze’s trim appearance and boyish exuberance that belie his adventurous nature. Take him at face value and you’d never suspect he’s perpetually scrambling down into caverns or picking his way across shifting mountainsides of scree.

He’s unassuming, so when he asks if you want to go on an adventure, you think, “Sure, why not? What trouble could I really get into with this guy?” Well, soon after I first met him, I found myself hanging from a 50-foot rope, inching my way down into a cavern in the heart of a Wyoming plateau perforated by a network of holes large and small and collectively known as Horse Thief Cave.

The trip, and Boze’s infectious passion for Horse Thief Cave, was proof positive that I had made the right decision to attend the University of Montana. I’d come for writing; Boze landed in the Department of Geosciences.

Boze knows Horse Thief Cave, and many other caves in that region, backward and forward, headlamp on or off. On that first trip, he led me and other greenhorns to an exposed wall in a vast cavern from which a shoulder of fossilized brain coral jutted, cadaverous and otherworldly. We passed from pitch darkness through chambers spot-lighted by small holes in the roof above us. The illuminated portions of cave floor were cluttered with jackrabbit bones – remnants of desperate, dodging, ill-fated flight from coyotes or hawks. We switched off our lamps and listened as our heartbeats filled our ears, watched as our minds spun northern-lights-like displays in the blackness that engulfed us. And then, when we’d had enough, we ascended that 50-foot rope back up to the blazing daylight.

So what does someone like Boze do for a living? Everything described above, as well as map caves, plumb the sea floor for greenhouse gases, conduct earthquake experiments ... all with only an undergraduate geosciences degree from UM. After he graduated in December 2007, Boze took a job with Sunburst Consulting, performing geologic analysis, mud logging and geosteering (aiming drills) in the Bakken Shale. It was tough, solitary work, and there were serious drawbacks. But there were perks, too.

“I learned a lot at Sunburst, often through a trial by fire,” Boze says. “They put you to work on the very first day and expect you to learn as you go. But the pay was good: I was able to pay off my student loans way ahead of schedule.

“However, I was frustrated by people’s general disconnection to their job. Many were just there for the paycheck, and I came to the conclusion that my primary motivation comes from the passion for why we do things as much as what we are doing. I realized I was much happier working in public service and felt that I could contribute to broader understanding of the natural world.”

Boze’s geologic analysis work led him to Jewel Cave National Monument in South Dakota, where he had interned as a college student. There he led mapping expeditions and conducted research on the geology and hydrology of the cave. He then transitioned to Menlo Park, California, where he worked in the United States Geological Survey’s Earthquake Science Center as a geophysicist. After Menlo Park it was Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Falmouth, Massachusetts, where he has worked since 2015. Cue the Arctic explorer bit.

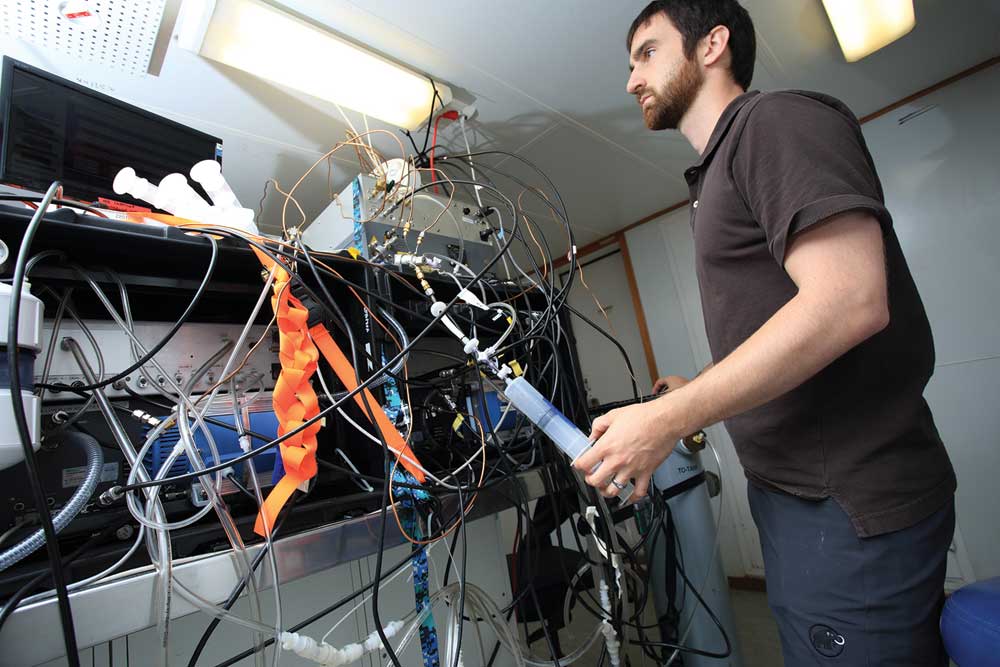

Boze and a handful of his Woods Hole colleagues now are researching gas hydrates, sometimes called methane clathrate, a substance believed to be commonly trapped deep on the ocean’s floor. Some see gas hydrates as a rich new fuel source, while others foresee a doomsday greenhouse gas set for release as the planet warms. To study this particular fossil fuel, Boze and his colleagues travel to some hard-to-reach places. Examples include coastal shelves accessed only by large research vessels in the open ocean and places like Svalbard, Norway, a cluster of islands situated about 500 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

In today’s job market saturated with degree-laden candidates, Boze, with his B.S. in geosciences, might not seem to stand out. But he insists his degree has given him more-than-solid footing, and he credits more than just his college coursework with his success. Specifically, he credits UM geosciences department faculty and their willingness to connect with their students.

“Marc Hendrix I liked because he impressed me,” Boze says. “After the first day, I realized he had memorized everyone’s name, including mine, which is weird and different. I definitely annoyed him a lot with my all-over-the-place attitude, but he had the patience to sit down with me, help me to focus and follow through.”

Hendrix laughs fondly when Boze is mentioned to him.

“I still have pictures and postcards on my office wall from Lee-Gray,” he says, following up by asking how Boze is doing out in Massachusetts and how his wife is faring. Boze and his wife, Brandi, were married in 2014. You can hear a touch of wistfulness in Hendrix’s voice when he learns Lee-Gray has a daughter, Adeline, who is going on a year now.

Hendrix’s interest in his students’ well-being is genuine. And his sincere concern for his students has translated into concrete careers for many of them. In 2011, Hendrix and UM colleague Michael Hofmann received a phone call that resulted in a business venture that has produced tremendous personal and professional opportunities for them, as well as eight UM geosciences graduates. The call was from a large oil firm that had a substantial backlog of core samples in need of analysis. It wasn’t long after that Hendrix and Hofmann launched AIM GeoAnalytics in Missoula. The company has grown steadily since.

“We’re trying to grow organically,” Hofmann says. “The last couple of years we’ve been adding more senior staff – people who have a lot of experience. We’ve started some employees as interns at first. It gives us a chance to know them and them a chance to know us.”

To date, AIM has provided internships to several UM students, expanding the company’s impact locally. The company is a hybrid endeavor. It is not a business-first undertaking but instead a private-public partnership with the University. That model allows Hendrix and Hofmann the flexibility to ensure the business provides opportunities for UM students and the research and exploration work that might not happen at an organization where profits come first.

“There are a lot of crossovers between what we do here at AIM and what we do for the University and with the University in terms of educating students,” Hendrix says. “That’s one of the reasons we were really enthusiastic to get this venture started. The University has a number of different revenue streams that include government sources and grants and contracts, but one of the things that has over the years been maybe underutilized is the idea of liaising businesses with the University to educate students in real-world, applied situations.”

Even if UM could do more liaising with the businesses world, something must be working. Talk to former UM geosciences chairman Jim Staub about how the program’s graduates fare in the real world, and you’ll learn that 75 percent of undergraduates find employment after graduation. For graduate students, that number jumps to 95 percent.

“There are two things going on,” Staub says. “The demand for geologists and geoscientists is expanding, and all us baby boomers are getting ready to retire or are retiring,” Staub says. “So, there’s a natural expansion and need for geoscientists. For at least the next 10 to 15 years, again because of the baby boomers, that need will only be exacerbated.”

Staub is a deliberate, no-nonsense man whose career has encompassed both the professional and the professorial. He grew up on a Pennsylvania dairy farm not far from the site of the nation’s first oil well, the Drake. He knew early on that dairy work was not for him and geology was, and in 1977 he took employment as a mine and exploration geologist and chief engineer with Cannelton Industries, a coal-sector company. Cannelton provided the coal needed for the manufacture of steel.

A lot has changed since the late ’70s, and Staub asserts the role of geologists and geoscientists, and the training that UM provides, has kept pace. He has seen a significant expansion in the opportunities available to geologists and geoscientists, chiefly in the environmental sector.

“However the environmental problem got there or whatever the societal need is, a geologist can help,” he says. “Let’s say you’re a rancher, and you need more groundwater. Is there a way, through applying basic ideas of geology and geoscience, to resolve the problem you have?

“At the end of the day, what we do as a profession is simply try to solve the needs of society.”

Sometimes problem-solving might translate to cleaning up a site that has run its course, such as an exhausted mine or an abandoned landfill. Tetra Tech, a Pasadena, California-based global consulting and engineering firm, has operated a Missoula office since 1997, and employs nine UM geoscience graduates – five in the environmental group (managed by Jerry Armstrong ’85) and four in the geotechnical and construction materials testing group (managed by Brian Crail ’16 and Chuck Goodman ’15).

Geotechnical engineer Marco Fellin echoes Staub’s sentiments: There is growth potential in the environmental and materials science fields.

“There’s a lot of opportunity within Tetra Tech for that,” Fellin says. Geoscience graduates are working in such diverse areas as mine-related cleanup, groundwater modeling, groundwater monitoring and cleanup, environmental site assessments, environmental permitting, environmental soil sampling and testing, and construction and geotechnical materials testing and inspection.

“Tetra Tech works for a diverse group of clients in Montana and throughout the world, and there’s a wide variety of work available,” Fellin says. “We work for private industry, local contractors, federal government agencies and the Montana Department of Transportation.

Recent geoscience-related work has included on-site soil sampling and testing following the California fires, oversight during sinkhole mitigation in Louisiana, setting up and operating the Missoula geotechnical testing laboratory, and oversight for load testing of ground anchors and materials testing for a UM building construction project.

Ask all involved parties and they’ll say the same thing: There’s both an increasing and diversifying demand for geoscience graduates. And, as demand grows and becomes more nuanced, institutions must provide more trained graduates who are ready to work.

“We’re right now in higher education at a point where things are changing,” Hendrix says. “A lot of universities are struggling financially, enrollments are down, and of course everyone is looking at the cost and the revenue.”

“Again, I’m a biased, applied scientist, but I think that students who are exposed to the applied world through university and business partnerships and competitive internships, for example, can gain valuable real-world perspectives that they wouldn’t otherwise have. The sense I get from being in the classroom is that students really want to know what goes on in the ‘real’ applied world and the skills they need to succeed there.

“In many ways the game is changing, such that those skills are evolving. There’s a lot more emphasis on integration of problem solving as opposed to rote memorization of facts. What I’m trying to say is, I think that one of the ways that universities can actually grow and provide more opportunities for students while bettering society in the process is through stronger ties with businesses.”

When Boze reflects on his career so far, he characteristically looks to the future instead of the past, and he expects, perhaps with as much excitement as ever, more changes ahead. Ask him where he would go if time and budgets were no barrier, and his reply is, without pause: Mars. Then, after a longer pause, he admits that journey may be one for his baby girl.

Ask him about more terrestrial career pursuits, specifically about his old adviser Hendrix’s take on universities’ need to expand private-public partnerships, and he concurs.

“I think that the study of geoscience is so dynamic, and the technology is changing so drastically so often, it’s critical to remain competitive,” Boze says. “Also, traditional natural resources are no longer as scarce as they used to be.”

Boze agrees with Fellin and Staub, too.

“I believe the future of geoscience will be in preservation of alternative resources,” he says. “I believe that open spaces and wilderness areas – both the preservation and restoration of them – will provide more sustained economic opportunity for Montana and the country than mining or extraction.

“And I hope I – and others like me from UM – will be there to help.”