- Editorial Offices

- 203 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

Lost and Found

Sue Purvis recovers the fatal and finds herself.

Writing a true story is like training a puppy. All the facts and context that rambunctiously romp into real life must be disciplined to trot out in a controlled way.

Susan Purvis thought she could make her own life’s story obey. She began writing a memoir about her beloved dog Tasha, a black Labrador retriever with obsidian fur, a heavy dose of mischief, and the heart of an angel. With nothing more than a yearning to save lives in extreme conditions, Purvis had trained Tasha for a search-and-rescue career that climaxed in one of the rarest and most precious experiences in her profession: finding a missing boy alive.

Then the leash snapped. Purvis’ husband of 18 years left her. Bereft suddenly of both her marriage and Tasha, who died in old age, Purvis was hit with the realization the story she was writing was a long way away from the story she needed to tell.

“I was the lost expert,” she says. “Then I realized I was as lost as anybody I ever found.”

In April 2019, her memoir “Go Find: A Journey to Find the Lost – and Myself,” released by Blackstone Publishing the previous fall, won a Nautilus Book Award. The book puts Purvis, who was born in Michigan, inside the unique club of literary figures from the Great Lake State who found success in Montana. It includes luminaries like Thomas McGuane, Jim Harrison and Doug Peacock, as well as “MeatEater” mogul (and 2000 UM graduate) Steven Rinella.

Purvis spoke in early March 2019 near the courtyard of a New York City apartment building where she stayed with a friend as she visited for an event hosted by the distinguished Explorer’s Club, of which she is a member. Dressed in jeans, a pink down jacket and a bright scarf, she was easy to spot amid the funereal dress of the natives. At times, she answered questions by reading passages straight from her book, like a cartographer who knows that sharing a hand-drawn map is better than explaining directions.

Purivs was born in the town of Marquette on the southern shore of Lake Superior. Her father, Harry, was a fish biologist who studied the devastating effects of introduced sea lampreys on native lake trout. For 62 years, he was married to her mother, Dottie, until she passed away in late March this year.

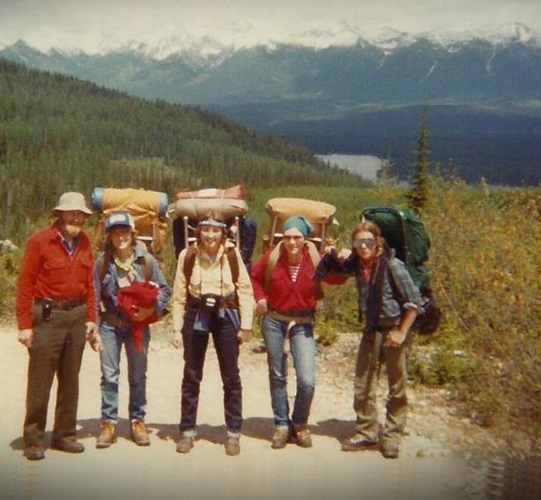

Purvis began writing when a middle-school teacher assigned her to keep a journal. The catalyst that set her life’s trajectory was a girlfriend who in high school invited Purvis to tag along on a family backpacking trip into Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness Area. In that June of her 14th year, gray clouds scudded through craggy, evergreen mountains and bathed her in freezing rain. She feared for her life crossing logs over raging creeks. A varmint ate half of one of her boots. She remembers being cold, hungry, frightened and matured by the experience.

“I think every kid needs to be shoved out in the wilderness, because now you have character in life,” she says.

The friend, Sara McClellan Fisher, now a life coach in Missoula, said she could look back and see how Purvis was affected.

“Her perspective on life changed, her perspective on what to do changed, she got on a different track,” McClellan Fisher says. “The world really became so much more open and available to her after that.”

Purvis decided three years later to come back to Montana. She wanted an educational experience that included elements from that backpacking trip: mountains, rivers, exploration. She enrolled in UM’s fledgling Wilderness and Civilization program. Her initiation into it was a birthday predawn hike to the top of Ear Mountain on the Rocky Mountain Front with legendary UM forestry Professor Bob Ream to watch the sunrise with a handful of her classmates. She called that bonding experience, “magical.”

Purvis decided three years later to come back to Montana. She wanted an educational experience that included elements from that backpacking trip: mountains, rivers, exploration. She enrolled in UM’s fledgling Wilderness and Civilization program. Her initiation into it was a birthday predawn hike to the top of Ear Mountain on the Rocky Mountain Front with legendary UM forestry Professor Bob Ream to watch the sunrise with a handful of her classmates. She called that bonding experience, “magical.”

Ben Super, director of development for UM’s W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, said Purvis “personifies” the Wilderness and Civilization program because her “life’s work is a fascinating interdisciplinary compilation of arts and sciences.” Andrew Larson, director of UM’s Wilderness Institute, added that the program “cultivates the ability to take risks, and Sue really illustrates that.”

To pay her tuition, Purvis worked at the UM Outdoor Program and led trips north to Canada and south to Utah’s national parks. On her own, she visited New Zealand, Australia and Antarctica.

“My middle name is ‘Adventure’ or ‘Explorer’,” she says.

In a geology class, she met her future husband, a man whom in the book she calls Doug. She described him as an attractive overachiever who specialized in rock formations of the Caribbean Islands. When she graduated in 1985, she took a job for a gold mining company, which sent her all over Montana. Her strongest memory of that time is a lonely stint living in Super 8 Motel in Helena.

She married Doug and came to live in an even stranger arrangement. Now both working for the same company, they were assigned to the Dominican Republic. But they were given the option to commute. They chose to fly back and forth between there and Gunnison, Colorado.

In nearby Crested Butte, Purvis heard a story that haunted her. It was about an avalanche that swallowed three young children, one of whom died. Purvis had taken a course in avalanche safety at UM and understood the horrible power of cascading ice and snow. What moved her so deeply about this tale was that a rescue dog had been unable to find the missing boy.

“I thought, ‘What if I got a dog and trained it to save lives?’” she says. “What if I vowed to never leave anyone behind.”

That quest turned to purpose and passion.

She adopted Tasha, five-and-a-half weeks old. Her book tells of her taking Tasha on a successful elk hunt:

“How could I have known that her ability to differentiate between human scents, between the living and the dead, would determine our successes and failures? That her reputation and mine would depend on it?”

Though Purvis knew nothing about dogs, she dedicated herself to training and caring for Tasha with the singlemindedness she displayed circuiting through the outdoors programs at UM. They became an elite team, fearlessly scouring avalanche scree, sometimes leaping from helicopters onto the unstable tops of mountains. They worked dozens of search and rescue missions, all in the Colorado Rockies.

But the truth of her job was different than what she imagined at the outset. She adopted Tasha hoping to make what she called a “live find,” to bring someone home safe, to quiet the ghost in her head of the boy killed in the Crested Butte avalanche. Yet she learned that avalanche dogs don’t find survivors, they find cadavers. Tasha fetched not hope but closure.

“All I wanted to do was save a life with this dog and that would give me validation,” Purvis said. “What I learned was empathy, empathy for the families. We really help the families not fall apart.”

Eventually, Purvis founded her own company, Crested Butte Outdoors. She gave medical lessons to guides who work in other extreme environments, like Africa’s Kilimanjaro and Nepal’s Everest.

In 2001, in the maze of the Big Blue Wilderness above Gunnison, Purvis and Tasha made their find of a lifetime. He was a lost 12-year-old hunter who became separated from his father and was too scared to move or make a sound. Camouflaged, he was invisible to every sense except Tasha’s nose. She found him curled in a ball at the base of a tall tree. He was their live find.

In 2001, in the maze of the Big Blue Wilderness above Gunnison, Purvis and Tasha made their find of a lifetime. He was a lost 12-year-old hunter who became separated from his father and was too scared to move or make a sound. Camouflaged, he was invisible to every sense except Tasha’s nose. She found him curled in a ball at the base of a tall tree. He was their live find.

With that rescue, Purvis fulfilled her original dream and had a precious moment with Tasha felt by few who work the avalanche trade. As she continued her work, she won renown. Colorado Rep. Scott McInnis commended her in the Congressional Record for her brave and successful work in dangerous alpine conditions.

She began to think about telling her story.

When Tasha aged into retirement, Purvis moved to Whitefish in 2007. She joined a writing group called Authors of the Flathead. The book she envisioned writing was a series of instructional stories about searches and rescues with Tasha, a subject she knew plenty about.

Then came her divorce. Which inserted into the story a question Purvis could not easily answer.

“How can I create this amazing bond with my animal, but I can’t do that with my human relationship?” she said.

Debbie Burke, a founder of Authors of the Flathead, who called herself one of the many “midwives” of the book, said it was difficult for Purvis to probe “the emotional territory underneath the story.”

“But ultimately the drive came from Sue,” Burke said. “The same wild-eyed determination that told her she could train a search dog to save lives also told her she could write a book. And she did.”

Purvis called the end result a mixture of “Into Thin Air,” “Marley and Me,” and “Eat Pray Love.”

Since publication, she has continued her work as a lead instructor with Wilderness Medical Associates and the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education and active membership with the American Avalanche Association, the Explorers Club, Wilderness Medical Society and ex Mountain Rescue Association. She also received high praise on her book from bestselling author Sebastian Junger, who called it “brave and profound.”

Purvis, at last, found a way to make her story heel, sit, stay.

Story by : Nate Schweber

Nate Schweber is a freelance journalist who graduated from UM’s School of Journalism in 2001 and lives in Brooklyn. His work appears regularly in The New York Times. He has written for Rolling Stone, Al Jazeera America, Anthony Bourdain’s Explore Parts Unknown, Narratively and Trout. He is the author of “Fly Fishing Yellowstone National Park: An Insider’s Guide to the 50 Best Places.” He sings in a band called the New Heathens.