- Editorial Offices

- 203 Brantly Hall

- Missoula, MT 59812

- (406) 243-2488

- themontanan@umontana.edu

A Recipe for Good

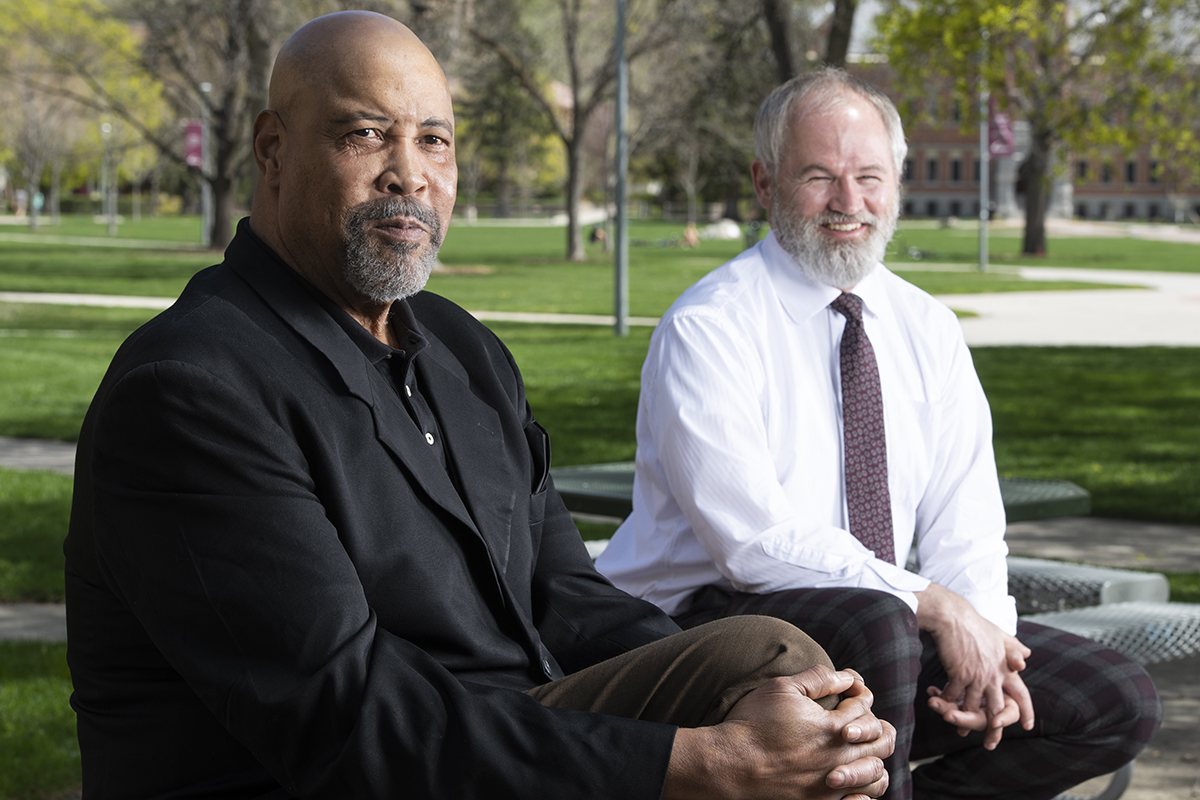

Tobin Miller Shearer parlays the personal and professional into his students and scholarship as a white man directing UM's African-American Studies department. It's not easy. But nothing important ever is.

Each fall, as the air turns crisp as a Bitterroot Valley apple and the maple trees of the University District flash gold, Professor Tobin Miller Shearer takes to his kitchen and bakes his famous pies.

One is a chocolate peanut butter pie that tastes like Reese’s Halloween candy. Another is a reverse pumpkin pie with the nutmeg in the crust. Also: salted caramel apple pie, shoofly pie (made with molasses), coconut cream pie, chocolate-jalapeño pie, banana cream pie, blueberry-blackberry-apple pie, chocolate ganache pie, lemon custard pie, sweet potato pie, open-faced apple pie, and chocolate malted pecan pie.

The pies are for his students, whom he invites to his house in the Lewis and Clark neighborhood for a sweet celebration. It gives him a self-effacing one-liner.

“Kids take my class because they know they might get a free piece of pie,” laughs Shearer, director of the African-American Studies program at the University of Montana.

Through his teaching and by his example, he has, in his 12 years at UM, changed numerous lives and influenced the culture of the state.

“He doesn’t just teach certain tenets or values, he represents those and follows those in every facet of his life,” says Meshayla Cox, 24, who credits Shearer’s class with her now working for the Montana Racial Equity Project in Bozeman. She added, “He’s a great friend, a great mentor, and honestly someone that I idolize greatly.”

Shearer, 55, a broad-shouldered man who flashes a gleeful smile beneath a hairstyle that fluctuates between military and Bernie Sanders, says he had a “peripatetic” upbringing. Born in Virginia, he was raised in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, interspersed with stints in Indiana and Ontario, Canada. His father was a Mennonite minister. Mennonites are peaceful Christians with the same Anabaptist roots as the Amish. For college, Shearer went to Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where hemet and married his wife, Cheryl.

After graduating, he took a job with the Mennonite Central Committee, moved to New Orleans, and worked at a live-in facility for homeless people and ex-offenders. His boss was a black man. That fact alone made Shearer uncomfortable. Six months in, Shearer had reached what he calls “a crisis point.” He recognized it for what it was: racism.

Shearer went to work. He reached out to mentors who helped him through “dealing with that prejudice internally,” he says. He paid close attention to his guidance and to his transformation. His mentors encouraged him to teach what he had learned to other members of the Mennonite community. With colleague Regina Shands Stoltzfus, Shearer co-founded an organization called Damascus Road (now called Roots of Justice). In a nine-year span, they led more than 400 anti-racism trainings.

“One of the things I admire about him is his willingness to do the work,” says Shands Stoltzfus, professor of Peace, Justice and Conflict Studies at Goshen College in Indiana. Affectionately, she says one of Shearer’s best traits is that he is a “history nerd.” In 2008 Shearer earned a doctorate in history and religion at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. His thesis was on the Mennonite community’s role in America’s civil rights struggle. He was then given an opportunity to move his wife and their two sons to Missoula to lead the African-American Studies program at UM, something he calls a “historic enterprise.”

For a state that reveres pioneers, the influence of African Americans on Montana cannot be overstated. Among the first non-Indigenous people to explore the land was York, one of the elite 33 members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The big game that is modern Montanans’ treasure was shielded from extinction in the late 1800s by African Americans in the Army’s 25th Infantry Regiment, the famous “Buffalo Soldiers” -- the original game wardens. In 1885, Mary “Stagecoach” Fields, of Great Falls, became the first African-American woman to work for the U.S. Postal Service. All that proud history and more helps explain why, in 1968, UM founded its African-American Studies program, making it the third-oldest in the nation. Yet Montana today is 89 % white and only 0.6% black. That paradox – such rich black history in the nation’s least-black state – rides in Shearer’s classes beside another obvious paradox, which he lays out at the start of every semester. He tells his new students that he is white, and that he knows it. Also that he understands, “there are tensions around me in that role and those tensions are appropriate.”  “But I think there’s a lot we can learn by stepping into them, exploring them and talking about the possibilities,” he says. In classes including “The Black Radical Tradition” and “Black: From Africa to Hip-Hop,” Shearer has incorporated his scholarship with his foundational eaching tenets of being welcoming, accepting and affirming. He learns all his students’ names right away, to show recognition and respect. In his most intense classes, he caps enrollment at around a dozen studets, to facilitate intimacy. And he has made his students share meals, to foster trust. Annually, he invites them to a “soup and pie” party at his home.

“But I think there’s a lot we can learn by stepping into them, exploring them and talking about the possibilities,” he says. In classes including “The Black Radical Tradition” and “Black: From Africa to Hip-Hop,” Shearer has incorporated his scholarship with his foundational eaching tenets of being welcoming, accepting and affirming. He learns all his students’ names right away, to show recognition and respect. In his most intense classes, he caps enrollment at around a dozen studets, to facilitate intimacy. And he has made his students share meals, to foster trust. Annually, he invites them to a “soup and pie” party at his home.

“It’s a great way to form community,” says Shearer, who this year became one of 12 faculty members in the state to win a MontanaUniversity System Teaching Scholar Award.Baking pies, Shearer says, is “part of my culture,” passed down from his grandmother, and is one more way of connecting with his slice of Montana. From the start, his goal has been toget his students to think and speak “with sophistication and nuance” about race. He is proud to have graduated students who now work in law, journalism, ministry, sports coaching

and social work. Shearer sees UM’s lopsided demographics – undergraduates are 79 % white and 1 % black – as motivational for his work.

“African-American history is something everyone should know,” he says. “Not just members of the African American community.”

One of the things that has made Shearer the proudest has been his assisting and advising members of the Black Student Union, the Black Solidarity Summit, the Montana Racial Equity Project, the Montana Human Rights Network and more. “We are actually at the height of groups and individuals who are deliberately organizing themselves to challenge and counter racism,” he says. “It’s very exciting and very fulfilling to be a part of that.”

Drawbacks, however, included death threats. Matter-of-factly, Shearer says death threats “come with the territory” for anyone dedicated to combating racism. He was aware when he moved to western Montana that the Pacific Northwest historically has incubated outposts of Neo-Nazis and other violent extremists. However, he says, these groups tended to flare and fade due to shoddy leadership and lack of inspiration. That changed in 2016 when Shearer was put on an online “watchlist” by a right-wing organization.It charged Shearer with spreading propaganda. Though Shearer was not intimidated, he learned that one of his African-American students suffered racist harassment. Other students expressed their outrage and fear. In response, he offered a class in spring 2018 titled, “White Supremacy History/Defeat,” teaching about the societal underpinnings of racism, and how parts of it have been dismantled.

This got him doxed, his personal information spread on more menacing websites. On a bulletin board in UM’s Liberal Arts Building there appeared a racist flyer. Its placement and trolling tone sent the creepy message that its maker was nearby, watching Shearer closely.

Additional threats against his life made him decide to hold his class in a location on campus known only to his students, and police.

“It’s one thing for me to get death threats, but it shouldn’t go to my students,” he says. “But my students were great, they were not at all daunted by it -- it was a very powerful experience for all involved.”

Yet more trouble was to come, from a quarter Shearer did not expect. In January 2020, UM’s Martin Luther King, Jr., Day Committee, with Shearer as chairman, announced the winners of its essay contest. Of the nine judges, five were people of color, but all six contest applicants were white. When photos of the four winners appeared, it set off a conflagration of online outrage from faraway commenters claiming the contest, and Shearer’s leadership, were invalidated by whiteness. Shearer had never before been so scorched by criticism, save for one familiar bit of language.

The Wall Street Journal editorialized: “He will be watched.”

Now scrutinized across the political spectrum, Shearer struggled with how to respond. He consulted with the people whom he calls “the grassroots,” his friends and mentors. One was Murray Pierce, UM’s multicultural affairs director. In the 1970s, Pierce took classes from the founder of UM’s African American Studies program, Ulysses Doss. Pierce thought Shearer’s new attackers had made, “surface-level judgements, pretty broad and not too deep.”

“[Shearer]doesn’t hide from racism,” Pierce says. “I respect him for it.” In February, Shearer published an open letter in Inside Higher Ed inviting all his critics to please have their way. Anyone, so long as they came in peace, and honestly engaged with the same history, ideas, and relationships as he and his students, were free to look and learn.

“I welcome you into my classes, watchers,” Shearer wrote. But, he added, none would ever, “cause me to back away from continuing our work.”

The work – as vital now as ever -- will not be finished anytime soon, but Shearer and UM are committed to it for the sake of the past and of the future.

Greeting all comers in the service of greater understanding is a recipe Shearer is happy to share.

***

Story by : Nate Schweber

Nate Schweber is a freelance journalist who graduated from UM’s School of Journalism in 2001 and lives in Brooklyn. His work appears regularly in The New York Times. He has written for Rolling Stone, Al Jazeera America, Anthony Bourdain’s Explore Parts Unknown, Narratively and Trout. He is the author of “Fly Fishing Yellowstone National Park: An Insider’s Guide to the 50 Best Places.” He sings in a band called the New Heathens.