Art For All Montanans

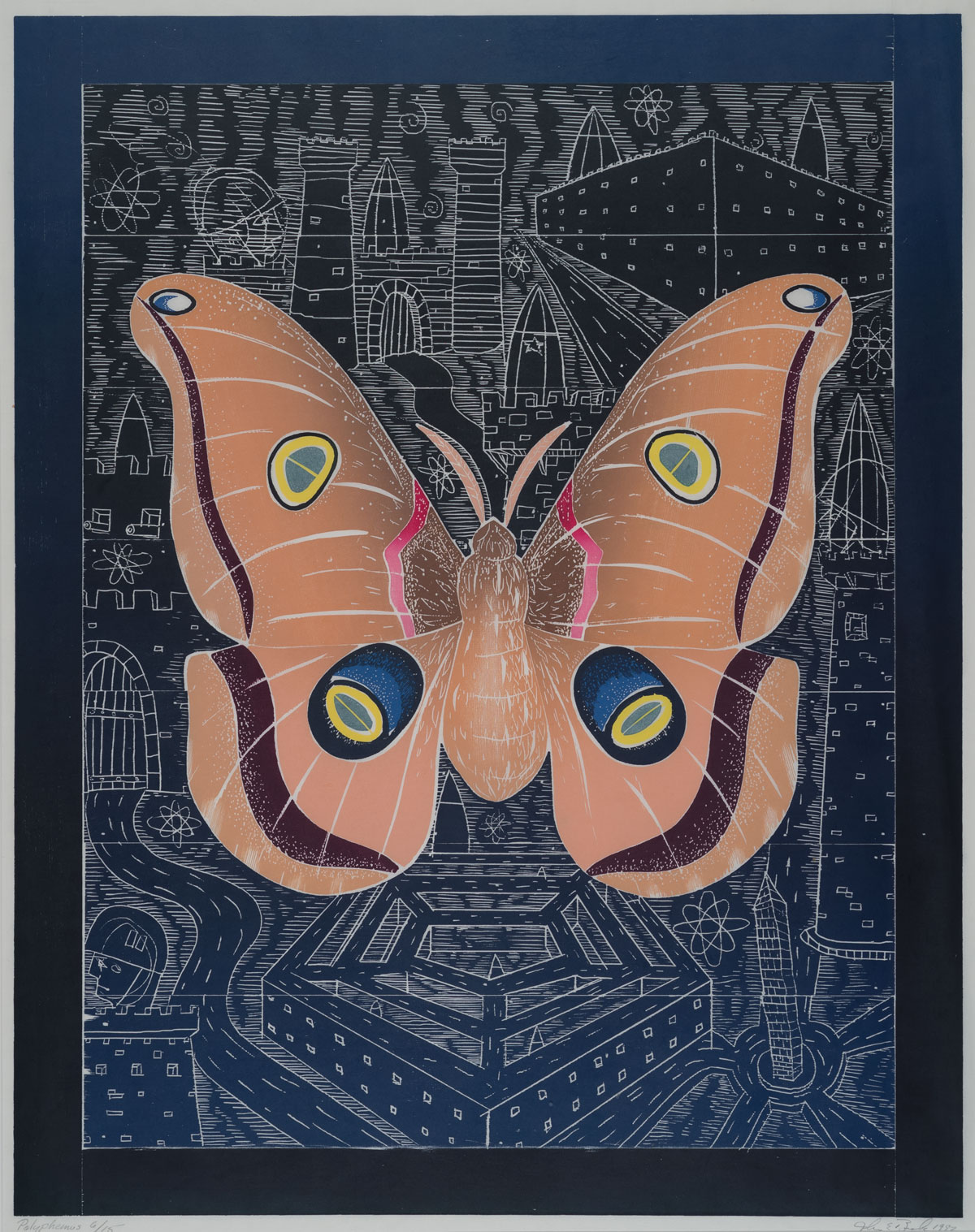

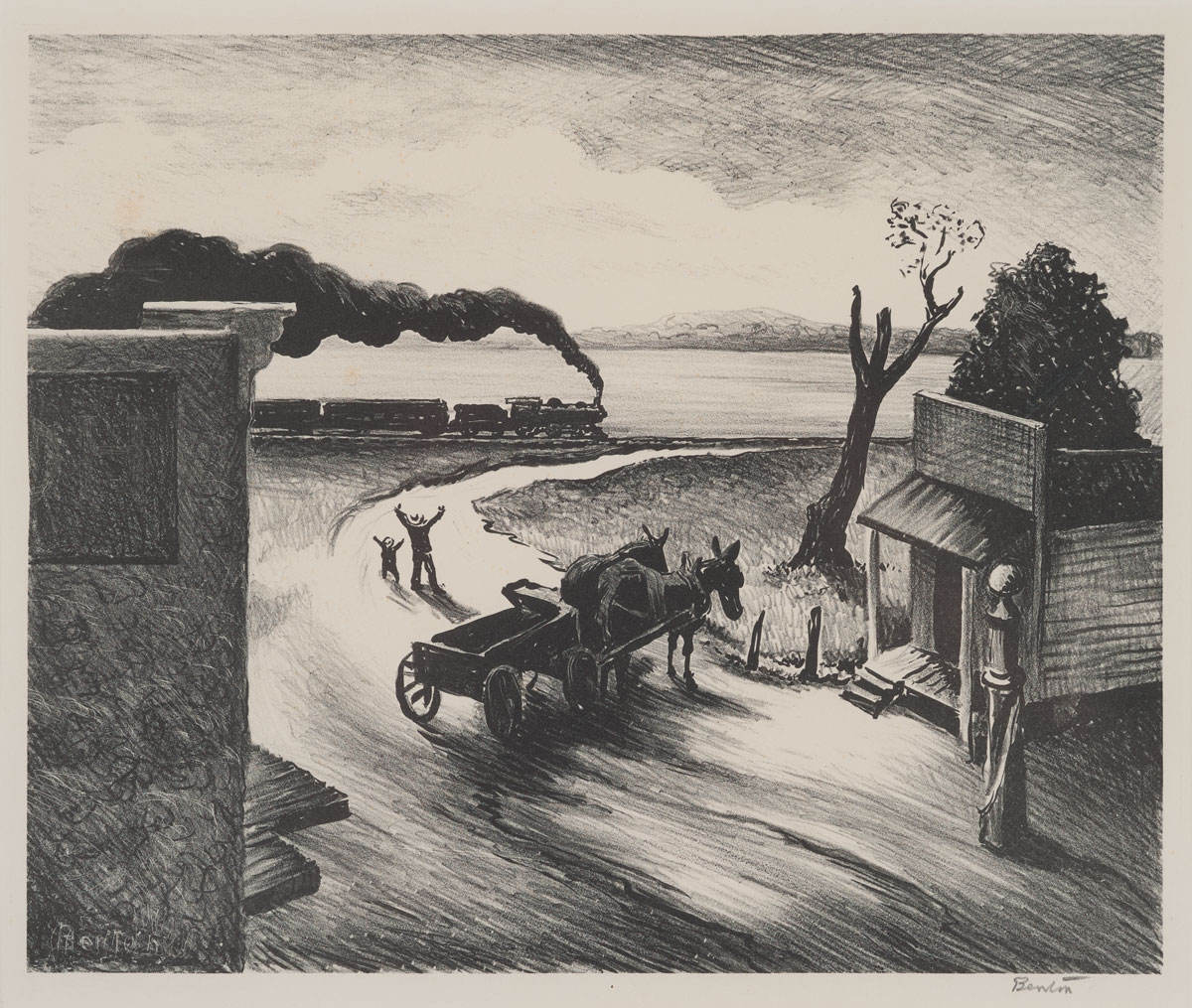

The MMAC is celebrating 120 years of its Permanent Collection in an exhibit that runs January 22 through May 23.

To honor the milestone, the museum has published a guide to a select 120 works called The Art of the State: 120 Artworks for 120 Years, all of which will be featured in the exhibit. They’ve landed some major donations recently, including one from the Crocker family that will help pay for museum staff each year. But part of the challenge has been letting Montanans know the collection exists, and that the art belongs to them. This exhibit is one way to do that. It will include audio tours and written works by a variety of community members, and there will be opportunities for viewers to respond to the artwork on the walls with written comments.

Despite having a collection that is mostly hidden away, the museum staff has worked hard to get the word out to the community. They are hosting living room soirees where MMAC Curator of Art Brandon Reintjes picks pieces from the collection and talks about the histories of various works and shares the stories that bring them to life.

The MMAC’s current museum spaces are located inside the Performing Arts and Radio/TV Center, and are what Barbara Koostra, director of MMAC, likens to closets. They’re small, isolated, and not necessarily amenable to an arts and culture atmosphere. Koostra’s and Reintjes’ hope for the future building is that it will showcase the art in a comfortable atmosphere, with space for lectures, gatherings, and, of course, exhibitions. And the public, who has not had adequate access to the enormous treasure in 120 years, can finally enjoy it in a space that feels less like a closet and more like a living room—and a home.

MMAC’s open gallery hours during the academic year are Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays from noon to 3 p.m. and Thursdays and Fridays from noon to 6 p.m. For more information, visit http://www.umt.edu/montanamuseum.